Why Verb Tenses and Modes Matter on AP Exams

If you’re gearing up for AP English Language or any AP course with a substantial writing component, verb tense and mode aren’t grammar trivia — they’re tools that shape clarity, tone, and rhetorical force. Scorers look for writing that communicates precisely and consistently. That means the verbs you choose must not only be correct in form but also appropriate to the purpose of the sentence, the scope of the argument, and the relationships between ideas.

Think about verbs as time and attitude engines. Tenses tell a reader when something happened (past, present, future). Modes, or moods, tell a reader how the writer views the action — as fact, possibility, desire, command, or condition. Together they establish logical sequencing, credibility, and rhetorical stance. On a timed AP response, small errors in these areas can interrupt the reader’s flow and cost you clarity points. On the flip side, skillful use of tense and mood can make an analysis feel alive, authoritative, and nuanced.

What AP Scorers Value

While the official AP rubrics emphasize thesis, evidence, reasoning, and organization, the underlying mechanics of language — including verb choices — are part of the transfer from claim to clarity. Here’s what exam graders usually reward:

- Logical consistency in tense across related clauses and sentences.

- Appropriate shifts in tense when signaling changes in time frame or hypothetical scenarios.

- Deliberate use of mood (indicative, subjunctive, conditional, imperative) to match rhetorical goals.

- Sentence-level variety that uses tense and mode to create emphasis or subtlety.

- Mechanically correct verbs (agreement, aspect, voice) that don’t distract from content.

Core Concepts: Tense, Aspect, and Mood Explained

Tense (Time in the Sentence)

At the most basic level, tense locates an action in time: past, present, or future. AP graders expect tense to be used logically. Use present tense to write about texts and universally true ideas (“In the passage, the speaker asserts…”). Use past tense for events fully situated in the past (“The author described a protest that occurred in 1968.”).

Aspect (How the Action Relates to Time)

Aspect helps you express whether an action is completed, ongoing, or habitual. The progressive (was walking, is walking) and perfect (has walked, had walked) aspects let you craft nuance. For instance, “The narrator has questioned memory” implies relevance to now, while “The narrator questioned memory” anchors the action in past narration.

Mood / Mode (The Writer’s Attitude Toward the Action)

Mood tells the reader whether the sentence expresses fact (indicative), command (imperative), wish or counterfactual (subjunctive), or conditional possibility (conditional). On AP essays, you’ll mainly use the indicative and conditional moods, but a correct subjunctive can sharpen a hypothetical analysis: “If the author were more transparent, readers would…”

Practical Rules AP Scorers Expect You to Follow

1. Use Present Tense for Literary Analysis

When you analyze texts, the literary present is the default: “In the poem, the speaker contends…” This signals that you’re discussing the text itself, not a historical event. That said, switch to past tense when you narrate author biography or publication history: “Published in 1922, the novel revolutionized…”

2. Keep Tense Consistent Within Ideas

Jumping nonsensically between tenses can confuse the reader and weaken your argument. Maintain a single time frame for each strand of reasoning. If you need to pause a claim to present a hypothetical, clearly mark the shift:

- Consistent: “The speaker compares memory to a map and argues that memory misleads.”

- Problematic: “The speaker compares memory to a map and argued that memory misleads.”

3. Make Shifts Intentionally and Transparently

Legitimate tense changes happen when the timeline changes or when you move between levels of abstraction. Make those shifts explicit with signal words (previously, later, meanwhile, now, by then) so a scorer sees the logic rather than a careless error.

4. Use Mood to Reflect Certainty and Stance

Conditional constructions are powerful in argumentative writing: “If schools prioritize standardized tests, creativity will suffer.” The subjunctive is rarer but useful for discussing unreal situations: “Were policymakers to consider student voice, outcomes might differ.” These forms show command over nuance — a subtle signal to scorers that your thinking is sophisticated.

5. Watch Verb Agreement and Irregular Forms

Basic agreement errors (subject-verb mismatch) are avoidable and can undermine credibility. Slow down during the final minute to scan for these errors. Irregular verbs — think lie/lay, sit/set, rise/raise — often trip students up. Know the common irregulars so your sentences read smoothly.

Examples That Demonstrate What Scorers Reward

Below are short before-and-after pairs that show how tense and mood choices change clarity and rhetorical effect.

| Before (Problem) | After (Improved) | Why It Works |

|---|---|---|

| “The author writes about grief and then described a scene of loss.” | “The author writes about grief and then describes a scene of loss.” | Consistent literary present keeps analysis in the same time frame. |

| “If the policy would be changed, students would see results.” | “If the policy were changed, students would see results.” | Subjunctive/conditional clarifies hypothetical nature. |

| “He had argued that this was true, and now he argues otherwise.” | “He argued that this was true, and now he argues otherwise.” | Past → present shift signaled with ‘now’; use past simple for prior claim. |

How to Practice Verb Control Under Test Pressure

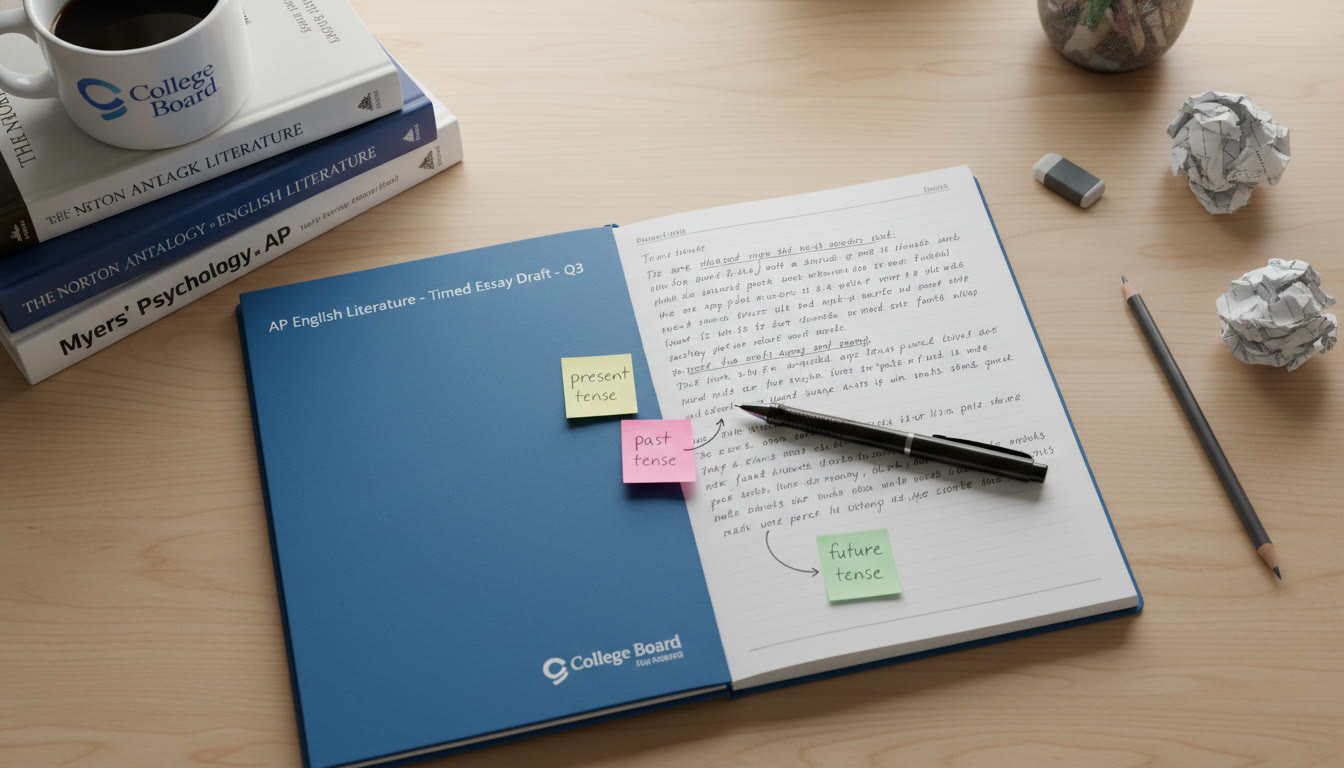

Drills That Build Automaticity

Practice should aim to make correct tense and mood choices automatic so you can focus on argumentation during the exam. Try these drills:

- Take a paragraph from a past AP prompt and rewrite it in the literary present, then in past narration, noting what changes.

- Create 10 conditional sentences about a single claim (If X, then Y) to practice the subjunctive and conditional mix.

- Time yourself writing 150–200 words where you intentionally vary aspect (perfect, progressive) to hone nuance without slipping into error.

Targeted Feedback and Why It Helps

Quick corrections are useful, but targeted feedback that explains why a tense shift is needed will help you internalize the rule. That’s why 1-on-1 guidance can accelerate improvement: a tutor can point out a pattern of errors — for instance, misuse of perfect aspect — and give targeted exercises to fix it. Personalized tutoring can also help you practice rhetorical uses of tense and mood, ensuring your grammatical choices amplify your argument rather than obscure it.

Common Pitfalls and How to Avoid Them

1. Unclear Shifts Between Narrative and Analysis

Students often summarize a text in past tense and then switch back to the present without clear markers. Use transition phrases to make the switch explicit: “At the time, the narrator believed…; however, the poem now suggests…”

2. Misusing the Subjunctive

The subjunctive is understated but meaningful. Avoid mixing it with indicative forms in the same conditional clause. Practice sentences like “If the community were stronger, it would resist isolation” until the structure feels natural.

3. Overuse of Passive Voice

Passive constructions aren’t wrong, but overreliance can hide agency and make arguments vague. Prefer active voice for clarity: compare “The argument is undermined by vague data” to “Vague data undermines the argument.” Use passive deliberately when the actor is unknown or unimportant.

4. Tense Problems in Embedded Clauses

Complex sentences with embedded clauses are common on AP essays. Check each clause for logical tense: “The study, which began in 1999, shows trends” (if the results still hold). If the clause is anchored in the past and doesn’t influence the present, use past perfect or past simple appropriately.

Scoring Considerations: What Low-Level vs. High-Level Responses Show

Scorers are trained to prioritize argument and evidence, but the level of control over language influences the score band a response falls into. A low-level essay might have persistent mechanical issues that obscure meaning. A high-level essay demonstrates precise control of grammar — including tense and mood — enhancing clarity and rhetorical effect.

Here’s a rough way to think about it:

- Low-level: Frequent tense errors, subject-verb disagreement, and confusing mood shifts that make the argument hard to follow.

- Mid-level: Mostly correct tenses with occasional slips that don’t wholly undermine meaning.

- High-level: Confident, purposeful tense and mood choices that strengthen nuance, rhetorical tone, and logical sequencing.

Sample Paragraphs: Annotated for Scorers

Below are two student paragraph samples. Each is annotated to show how tense and mode affect scoring.

Sample A (Good)

“In her essay, the author insists that technology reshapes memory. She draws an extended comparison between digital archives and personal recollection, arguing that the former prioritizes retrieval over nuance. If readers accept this premise, they might begin to reevaluate how they document private life.”

Notes: Uses literary present for textual claims, keeps consistent tense, uses conditional mood appropriately to show implication. These choices make the reasoning clear and rhetorically apt.

Sample B (Needs Work)

“The author insisted that technology is reshaping memory and then she was making a comparison which suggested that archives are better than memories. If people would accept that, they were reevaluating their lives.”

Notes: Mixed past and present tenses, awkward passive constructions, and incorrect conditional forms make the argument vague. These mechanical issues would likely lower the score because they interfere with clarity.

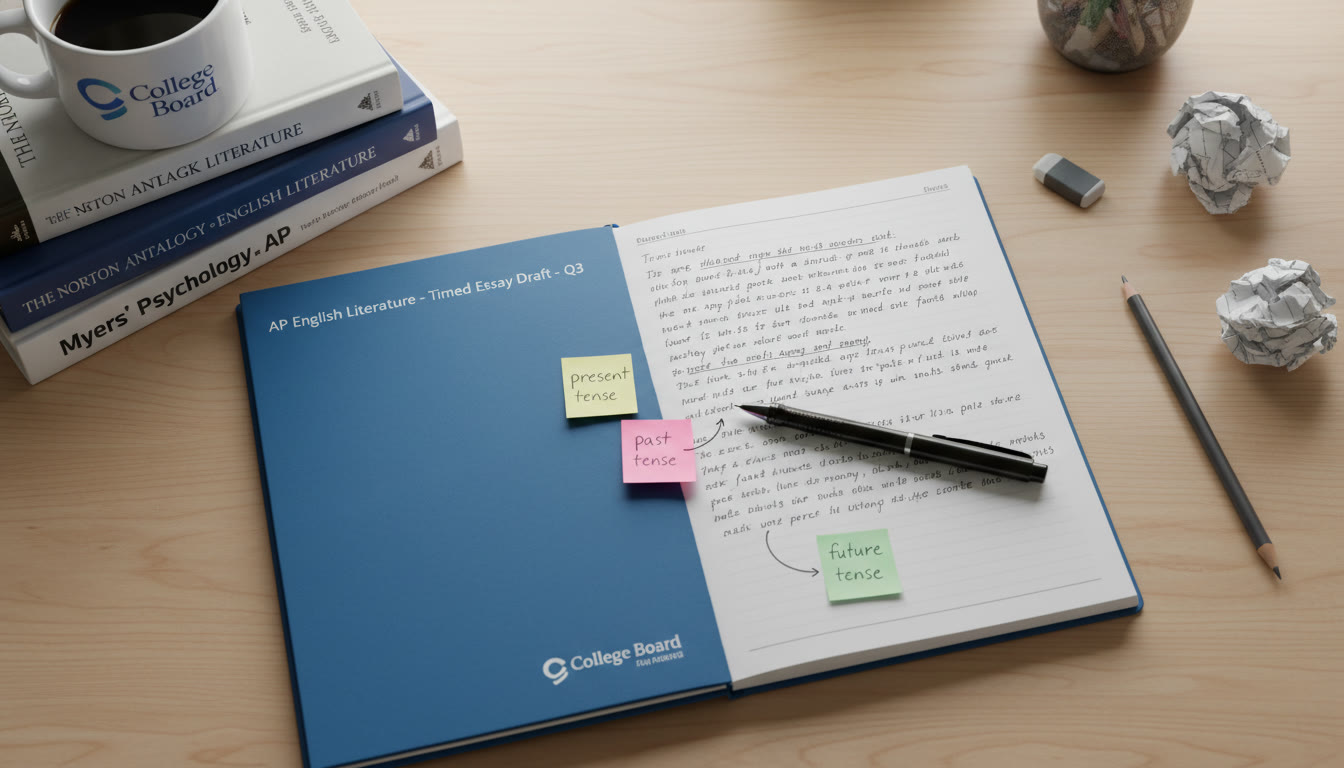

How to Edit for Tense and Mode in a 40–50 Minute Essay

Time management matters. You don’t want to waste precious minutes on minor edits, but a strategic pass can catch errors that distract scorers.

- First 5–8 minutes: Plan your thesis and story arc. Decide which time frame(s) you’ll use (literary present, historical past, etc.).

- Middle 25–30 minutes: Draft with an eye toward consistent tense within each line of reasoning.

- Last 5–7 minutes: Read aloud or silently scan for tense shifts, subjunctive misuse, and subject-verb agreements. Fix glaring issues, especially in your thesis and topic sentences.

A Handy Reference Table: When to Use Which Form

| Situation | Recommended Tense/Mood | Example |

|---|---|---|

| Analyzing a text’s content or argument | Literary present (Indicative) | “The narrator asserts that silence signals complicity.” |

| Describing historical events or author biography | Past simple or past perfect | “Published in 1954, the novel captured readers’ attention.” |

| Discussing implications or hypothetical outcomes | Conditional or subjunctive | “If policymakers were to act, the results could change.” |

| Emphasizing ongoing or habitual actions | Present progressive or simple present | “The study continues to inform public debate.” |

Study Plan: Two-Week Sprint to Tighten Tense and Mood Control

If you’ve got roughly two weeks before a practice exam or the real thing, here’s a compact plan to sharpen your tense and mood skills.

- Days 1–3: Review fundamentals — literary present, past simple/perfect, progressive, conditional, and subjunctive. Create one-page cheat sheets with example sentences.

- Days 4–6: Do focused drills on conditional and subjunctive sentences. Write 10–15 hypotheticals daily and check them carefully.

- Days 7–10: Take past AP prompts and rewrite sample essays to tighten tense. Swap perspectives: change a paragraph from past narration to literary present and observe effects.

- Days 11–12: Timed practice essays (40–50 minutes). Focus your revision pass exclusively on tense/mood and mechanical accuracy.

- Days 13–14: One last timed essay with targeted feedback from a teacher or tutor. Use that feedback to make a final checklist you can scan during the exam.

How Personalized Tutoring Can Fit Naturally into Your Prep

Grammar rules can be dry, but they come alive when tied to your argument and voice. Personalized tutoring — for example, Sparkl’s tailored 1-on-1 guidance — can accelerate that process. A good tutor spots recurring tense-pattern errors, suggests short targeted exercises, and models rhetorical uses of mood. Tutors also help you practice the exact kind of timed editing you’ll need on test day: quick scans that save points and improve clarity. When feedback is tailored to your writing, improvements stick faster than random drills.

Final Checklist to Leave a Strong Impression on Scorers

In the last moments of a timed AP response, run this quick checklist:

- Thesis and topic sentences use consistent tense appropriate to analysis.

- Conditional and subjunctive constructions are used clearly when signaling hypotheticals.

- Subject-verb agreement is intact in complex sentences.

- Passive voice is used intentionally, not out of habit.

- Embedded clauses are checked for tense logic relative to the main clause.

Closing Thoughts: Show What You Know With Clarity

Verb tenses and modes are small levers that produce big results. They refine meaning, shape nuance, and display a level of control that AP scorers notice. You don’t need to deploy every advanced construction; you need to use the right one at the right time. Practice deliberately, use targeted feedback (for instance through tailored tutoring sessions), and treat tense and mood as rhetorical choices rather than mechanical afterthoughts. When your language is clear and purposeful, your ideas will be easier to score highly — and you’ll write with a confidence that shines through even under time pressure.

Remember: the writing score rewards clarity and reasoning above all. If your verb choices support the argument and improve readability, you’re already on the right track. Good luck — and when you want a focused plan tailored to your exact weaknesses, targeted 1-on-1 tutoring and AI-driven insights can make each study minute count.

No Comments

Leave a comment Cancel