Welcome — Why This Guide and Who It’s For

If you’re standing in the middle of your studio, surrounded by armatures, clay, foam, found objects, or a dozen half-finished maquettes, take a breath. You’re doing the real work: making. This guide helps you translate that making into a focused, compelling AP 3‑D Art and Design portfolio that readers can understand and score fairly.

This piece is written for students preparing the AP 3‑D portfolio (Sustained Investigation + Selected Works). It explains portfolio structure, unpacks rubric language in plain English, and gives hands-on strategies for photographing three-dimensional work, framing inquiry statements, and organizing images and written evidence so your ideas and skills shine.

Quick Overview: What the AP 3‑D Portfolio Actually Is

The AP 3‑D portfolio evaluates two major things: your process and your outcomes. Those come through two portfolio sections:

- Sustained Investigation (60% of the score) — a coherent body of work (15 images) accompanied by written evidence describing the inquiry and your development through practice, experimentation, and revision.

- Selected Works (40% of the score) — five finished works (10 images for 3‑D: two views each) with brief written descriptions about medium, process, and ideas.

The portfolio is submitted digitally. Photos become your clay, your installation, your negative space — they must communicate the work’s scale, form, texture, and the decisions you made.

Understanding the Rubric Language — What Readers Are Looking For

The AP scoring rubric is written in specific terms: “sustained investigation,” “skillful synthesis,” “practice, experimentation, and revision,” and “communication.” Let’s unpack each phrase into everyday study goals you can act on.

Sustained Investigation

What this means: Readers want to see an inquiry (a question, problem, or deep interest) that guides multiple works over time. It isn’t one project with a few variations — it’s evidence that you pursued an idea through making, testing, failing, and refining.

How to show it:

- Start with a clear inquiry statement that names your curiosity in 1–2 sentences.

- Include documentation (images) that demonstrates stages: research, early experiments, prototypes, and final works.

- Use written evidence to explain pivotal decisions: why you changed a material, why you chose a scale, or how you combined processes.

Practice, Experimentation, and Revision

These words appear often in the rubric because they indicate learning. The AP readers are looking for a process, not just polished outcomes.

Concrete signs of this in a portfolio:

- Multiple iterations of the same idea that show change (e.g., three maquettes that get progressively more resolved).

- Experimentation with at least two different materials or processes that inform the final work.

- Written descriptions that reference what you learned and how you altered the work as a result.

Skillful Synthesis of Materials, Processes, and Ideas

“Skillful synthesis” means your final works combine technical ability, thoughtful concept, and an intentional material/process relationship. It’s not enough to be technically excellent; your choices should support your idea.

Questions to ask when planning Selected Works:

- Does the material choice amplify the concept?

- Does the process create a necessary effect that couldn’t be achieved any other way?

- Do multiple works show a coherent voice or viewpoint?

How Portfolios Are Scored — The Practical Breakdown

Your portfolio is scored on a 1–5 AP scale. Behind that number, each section contributes differently:

| Portfolio Section | What It Includes | Percent of Score |

|---|---|---|

| Sustained Investigation | 15 images + written evidence describing your inquiry and development | 60% |

| Selected Works | 5 works (10 images for 3‑D) + brief descriptions of materials/process/ideas | 40% |

Each component is scored separately by trained AP readers, then combined for the final portfolio score. Readers evaluate both the images and the writing: clarity in your statement can change how they perceive an image.

Writing the Sustained Investigation: A No‑Nonsense Formula

Most students underuse the writing portion. Good writing doesn’t have to be long; it just needs to be clear about your inquiry and process. Here’s a simple, effective structure:

- Inquiry Statement (1–2 sentences) — What question or interest guided your work? (Example: “I investigated how negative space and modular repetition can create site‑responsive sculptures that change as viewers move around them.”)

- Context and Research (2–3 sentences) — Briefly mention inspirations, artists, or materials you explored.

- Development Summary (4–8 sentences) — Highlight experiments, key iterations, and a turning point where an idea either worked or needed rethinking.

- Reflection (2–4 sentences) — What did you learn? How might this investigation continue beyond the portfolio?

Keep language concrete. Swap adjectives like “interesting” for specifics: “By switching from plaster to expanded polystyrene, I reduced weight and increased the ability to carve negative forms, which shifted how light defined the piece.”

Common Pitfalls in Writing

- Overly generic language that doesn’t explain decisions.

- Too much art-historical name dropping without tying influences to your choices.

- Describing materials without explaining why they mattered to the idea.

Selected Works: Choosing and Photographing Pieces That Count

The Selected Works section is your showstopper: five works that demonstrate your strongest synthesis. For 3‑D, each work needs two carefully chosen views. Plan these photos the way you would plan a mini installation shoot.

How to Choose the Five Works

- Pick works that together display range without losing coherence—different scales, materials, or tactics while showing a consistent voice.

- Include at least one piece that demonstrates technical mastery; include one that demonstrates conceptual depth.

- If a work appears in Sustained Investigation, it can also be in Selected Works, but you don’t have to duplicate pieces across sections.

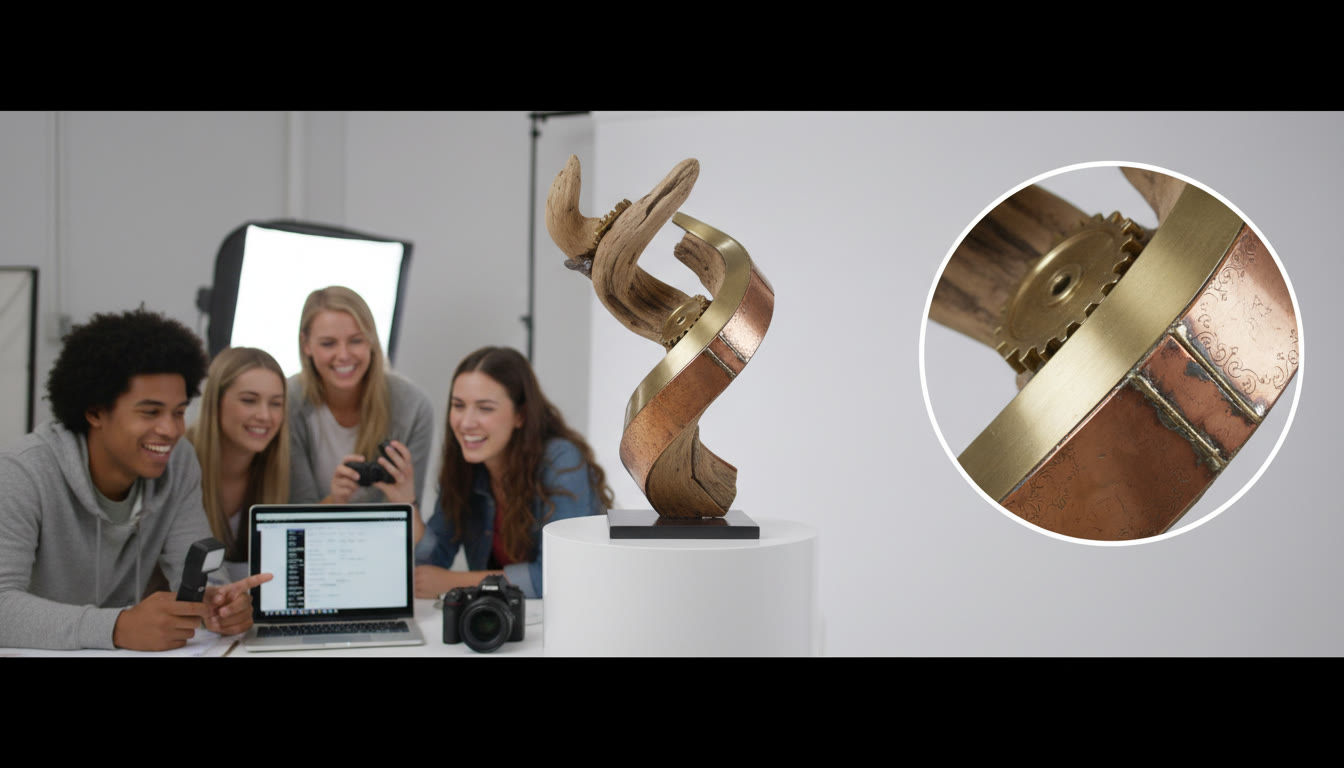

Photography Tips for 3‑D Work

- Use clean backgrounds and consistent lighting to show form and texture. Natural light with a reflector often works well; soft side lighting reveals surface.

- Include a scale cue when necessary — a hand, a chair, or even a small ruler in an unobtrusive corner.

- Shoot multiple vantage points: front, 3/4, back, and a close-up detail. Then pick the two most informative images for submission.

- Avoid videos. Still images are required; sequence your images to tell the story (overall view + detail or second angle).

Organizing Your Digital Portfolio: Sequence, Clarity, and Intent

Think of the digital portfolio as a short exhibition. Sequence matters. Arrange images so a reader can follow your inquiry through early experiments to resolved pieces.

Suggested image sequence for Sustained Investigation (15 images):

- Research/Inspiration images (1–2)

- Early experiments/prototypes (4–6)

- Refined works and turning points (3–4)

- Final pieces that reflect synthesis (3–4)

Use captions and your written evidence to connect the dots. If an image shows a prototype that informed a final piece, name it. Readers appreciate clear, honest documentation of reasoning.

Practical Rubric Translations — What Separates a 3 from a 5

Rubric language tells you what to emphasize. Below is a simplified translation of what each score range tends to reflect in portfolios.

| Score Range | What Readers See |

|---|---|

| 5 | Clear, focused sustained investigation; multiple successful experiments and revisions; strong technical skill and expressive synthesis; writing that explains decisions and development. |

| 3–4 | Competent exploration and outcomes; some evidence of iteration and material exploration; writing adequate but sometimes vague or uneven. |

| 1–2 | Limited investigation or little evidence of sustained development; fewer successful experiments; writing may be missing or too general. |

Examples and Short Case Studies

Below are three condensed, realistic scenarios and how a student could frame their portfolio choices and language.

Case A: Modular Ceramics Investigation

Inquiry: Explore how modular ceramic units reconfigure to alter negative space and light penetration in a site-responsive installation.

Strategy: Document early slab and hollow-form experiments, glaze tests, and three installation trials. Use final Selected Works as resolved modules photographed in two configurations. Writing focuses on why modularity matters and how glaze choice affected translucency and perceived scale.

Case B: Wearable Sculpture and Interaction

Inquiry: Investigate the relationship between body movement and sculptural armature in wearable pieces that challenge notions of personal space.

Strategy: Include performance stills, maquette development, and technical tests (straps, joints). For Selected Works show two views: on-body and off-body detail. Writing ties the performative aspect to choices in weight distribution and connection points.

Case C: Reclaimed Materials and Structural Logic

Inquiry: Examine how reclaimed wooden parts suggest new structural logics when reassembled into cantilevered forms.

Strategy: Show source materials and experiments with joinery, strengthening, and finish. Selected Works highlight successful strategies for stability and aesthetic cohesion. Writing describes failures and the structural lessons learned.

Checklist Before Submission

- 15 well-captioned images for Sustained Investigation, in a logical sequence.

- Written evidence that includes a concise inquiry statement and clear development narrative.

- Five Selected Works with two images each and concise descriptions of idea, materials, and process.

- Photographs that convey scale, texture, and spatial relationships.

- Proofread all writing; clarity counts.

- Follow your teacher or AP Coordinator’s internal deadlines — they often set earlier submission dates.

How to Use Feedback and Iteration — Make the Rubric Work for You

Rubrics aren’t just for scoring; they’re a roadmap for improvement. Treat each rubric phrase as an instruction: if the rubric values “revision,” plan checkpoints in your semester to experiment and iterate. Invite feedback early — from peers, teachers, or even targeted tutoring sessions that offer 1‑on‑1 guidance.

Personalized tutoring, like Sparkl’s 1‑on‑1 mentoring and tailored study plans, can give you specific feedback on sequence, photographic choices, and how to tighten your written evidence. When you combine clear rubric-focused goals with individualized coaching, the path to a strong portfolio becomes less mysterious and more strategic.

Time Management and Project Planning

Good portfolios are rarely the result of last-minute bursts. Use a semester plan that carves out blocks for research, experimentation, critique, documentation, and finalizing. Here’s a practical timetable for a school year:

- Weeks 1–6: Research and initial experiments (formulate your inquiry)

- Weeks 7–14: Focused making and iterative testing

- Weeks 15–18: Consolidation — choose works for Selected Works and refine them

- Weeks 19–22: Photo documentation, final revisions, and writing

- Submission weeks: follow coordinator deadline, and review one last time with an instructor or tutor

Ethics, Originality, and AI Guidance

Be transparent about sources. If a preexisting artwork inspired you, cite it in your image descriptions. The AP program emphasizes originality — your portfolio must be your own idea and execution. Note that policies prohibit using AI to generate artwork for submission, and any assistance should be documented if required by your instructor.

Final Words: Confidence, Curiosity, and Craft

At its best, the AP 3‑D portfolio is less about playing to a test and more about presenting a disciplined curiosity. If you show a genuine inquiry, clear evidence of learning through making, and thoughtful synthesis of materials and ideas, readers will notice. Art is messy; that mess is evidence of thinking. Document it well.

If you want targeted help—say, a critique of your image sequencing, or help tightening inquiry language—consider short, focused sessions of 1‑on‑1 tutoring. Personalized attention can transform a portfolio from good to outstanding by aligning your studio practice with the rubric’s language and expectations.

Resources to Draft From (In-Studio Exercises)

- Make three small, fast maquettes using different materials; photograph each and write one sentence about what each taught you.

- Create a two-minute process video (for yourself) showing a key step; extract two stills that display change and detail for your portfolio.

- Write a one-paragraph inquiry and then bullet three measurable goals you can test in the next six weeks.

Closing Encouragement

You’re building a story that only you can tell — a story of curiosity, risk, and making. Treat the rubric as a translator: it takes what you already do in the studio and helps you say it clearly so readers can understand the depth of your practice. Keep iterating, be specific in your writing, and let your images do the heavy lifting. You’ve got this.

If you’d like help translating a rough inquiry into a tight Sustained Investigation statement or selecting five works that show range and focus, reach out for tailored feedback and tutoring support to refine your strongest narrative.

No Comments

Leave a comment Cancel