Why Organizing Sources Matters for Your AP Research

If you’re working on an AP research project or a literature review for an Advanced Placement course, you already know that the reading pile can grow faster than your free time. What feels like a mountain of articles, books, and class notes can quickly become an unhelpful pile unless you create a simple, dependable system for organizing sources. Good organization doesn’t just save time — it transforms scattered facts into coherent arguments and makes your work look polished, credible, and, frankly, smarter.

Start with Strategy: Define Your Research Question and Scope

Before you collect a single source, be crystal clear about your research question. AP Research and AP Literature tasks reward precise focus, not breadth for breadth’s sake. A narrow question helps you filter sources and saves hours of irrelevant reading.

Ask yourself:

- What am I trying to prove, explore, or understand?

- What are the key concepts and keywords?

- What time period, geographic area, or population is relevant?

Example: Instead of “How does war affect literature?” try “How did World War I influence narrative technique in British modernist poetry (1914–1930)?” The second question points you to specific authors, years, and stylistic traits, which makes source organization manageable.

Design a Simple Folder Structure: Digital and Physical

Decide on a consistent place to keep everything. Many students prefer digital-first systems because they’re searchable and portable, but a small physical binder for printed copies can be useful for close reading.

Sample folder structure (digital):

- Project Root Folder (CourseName_ProjectTitle)

- — References (PDFs, scans)

- — Notes (Markdown, Word, or text files organized by theme)

- — Outlines (draft outlines and thesis versions)

- — Tables and Figures (data, charts)

- — Final Drafts and Submissions

Keep naming consistent: Author_Lastname_Year_Title.pdf. That tiny consistency prevents chaos later.

Use a Reference Manager — Even a Small One

Reference managers are lifesavers. They store citations, PDFs, and notes together and can produce a bibliography in the format your teacher prefers. You don’t need to learn everything at once; even basic use saves time.

- Why use one? Automatic citation formatting, quick searches, and attachment of PDFs and notes to each reference.

- What to store: full citation details, PDF (if available), a 1–2 sentence summary, and tags (keywords).

If you’re new to them, focus on three features: easy import from library databases, tagging, and a reliable search function. Learn the export for a Works Cited/Bibliography and test it early.

Develop a Note-Taking Taxonomy

Not all notes are equal. Train yourself to take three kinds of notes for each source:

- Bibliographic Note: Full citation and where you found it (database, URL, date accessed).

- Summary Note: 1–3 sentences capturing the source’s main claim and relevance.

- Analytical/Reflective Note: Your thoughts: how does this support or challenge your thesis? What methods were used? Any weaknesses?

Add quick tags to each note like Method:Qualitative or Theme:Identity so you can pull together themes later.

Example Note Template

| Field | Entry |

|---|---|

| Citation | Author Name, Title, Journal/Book, Year |

| Summary | One-sentence core idea of the source |

| Key Quotes | Short quotes with page numbers |

| Methods/Approach | Quantitative / Qualitative / Theoretical |

| Relevance | Why this helps your research question |

| Tags | Two to five keywords for searching later |

Tagging and Thematic Organization

Tags are your best friends when synthesizing a literature review. Create 8–15 persistent tags for your entire project (e.g., Narrative Technique, Modernism, Trauma, Methodology, Primary Source). Use the same tag names everywhere.

Benefits of consistent tags:

- Quickly assemble all notes on a theme into a single page or document.

- Reveal gaps in the literature where you need more sources.

- Allow overlapping themes — a source might be tagged both Primary Source and Trauma.

Curate — Don’t Collect

It’s tempting to save everything “just in case,” but a curated collection saves you the agony of re-reading irrelevance. Apply a quick 60-second rule when you open a paper: can you identify the thesis, method, and one line of relevance? If not, archive it with a short note and move on.

Quick Curating Checklist

- Does the paper address my keywords or concepts?

- Is the method trustworthy and relevant?

- Will this source likely appear in my literature synthesis?

Workflows That Scale: From Reading to Draft

Turn your organized sources into writing with predictable workflows. Here’s a step-by-step plan many successful students use:

- Collect 20–30 reliable sources that pass your 60-second rule.

- Create summary notes and tag each source.

- Write a one-page literature map: group sources under headings like “Themes,” “Methods,” and “Debates.”

- Draft topic sentences for each paragraph in your review based on the grouped themes.

- Assemble evidence: pull quotes and paraphrases from your notes into the draft with citations.

- Write synthesis paragraphs that compare, contrast, and evaluate — not just summarize.

This repeatable workflow keeps the project moving without ever losing sight of the main question.

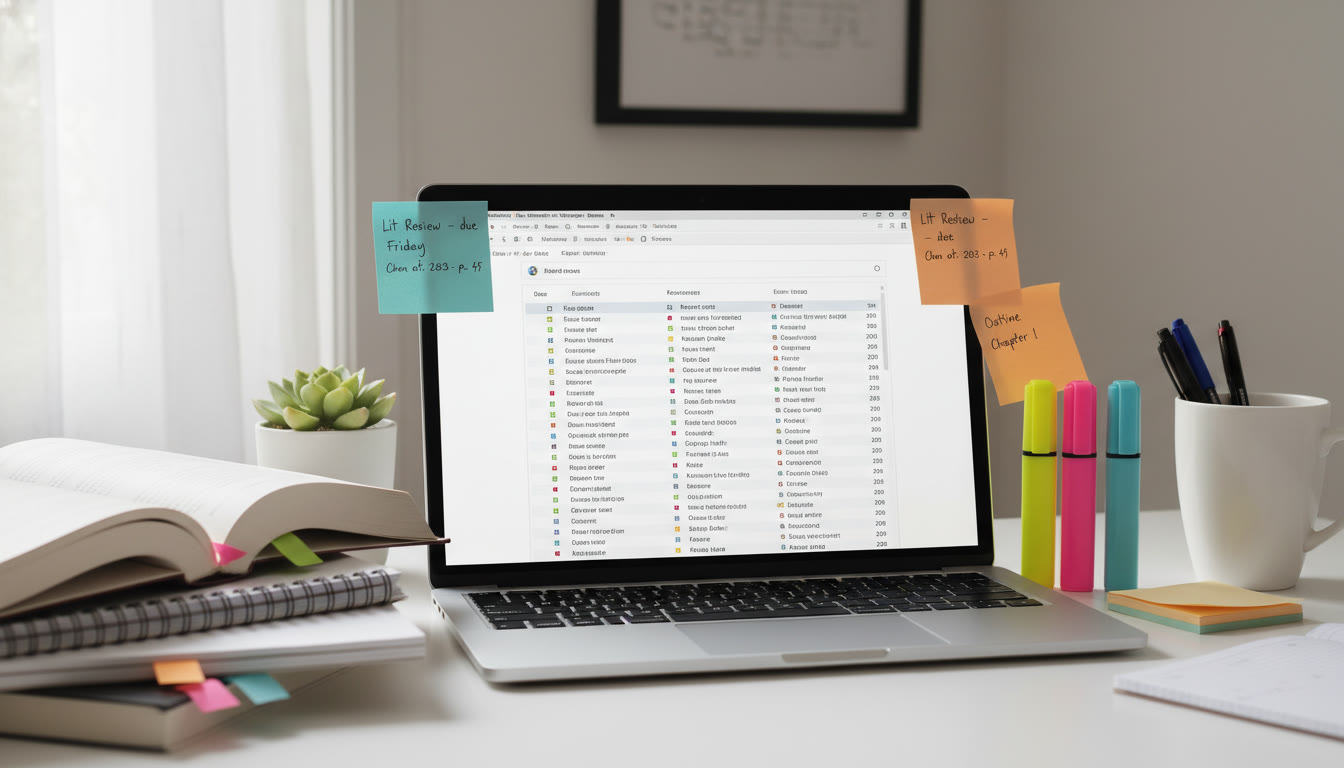

Tables and Matrices: Visual Synthesis Tools

Tables are invaluable for turning qualitative literature into digestible comparisons. Here’s a compact example you can adapt for AP-level literature reviews:

| Source | Year | Method | Key Finding | Relevance / Tag |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Smith | 1920 | Close Reading | Emphasizes fragmentation as aesthetic choice | Narrative Technique |

| Garcia | 2009 | Historical Analysis | Contextualizes poet’s war experience | Context, Trauma |

| Lee | 2018 | Comparative Study | Shows cross-national trends in modernist imagery | Comparative, Imagery |

Use tables to present methods, sample sizes (if any), theoretical lenses, and conclusions. Tables help when you need to write synthesis paragraphs: glance at the matrix and start comparing rows.

From Notes to Paragraphs: Writing with Sources

A literature review isn’t a long list of summaries. Your goal is to explain how the body of work fits together and what gaps remain. A handy paragraph structure is:

- Topic sentence that states the theme or debate.

- Two to three sentences that summarize contrasting views.

- One sentence evaluating the strengths/weaknesses of that body of work.

- Concluding sentence that connects back to your research question.

Always embed citations as you paraphrase or quote. If you’re using a reference manager, insert placeholders early so you don’t lose track of which idea came from which author.

Quote Smart: Use Sparingly and Strategically

Quotations are powerful when the author’s phrasing is unique or essential for analysis. For AP-level writing, prioritize short, meaningful quotes paired with interpretation. Don’t rely on long quotations as a substitute for synthesis.

Track Your Gaps and Next Steps

Keeping a live “To-Find” list prevents repeated searches. As you map themes, make a list of the perspectives, methods, or time periods missing from your review and set small weekly goals to locate them. This is where a focused tutor can help accelerate progress: Sparkl’s personalized tutoring, for example, offers 1-on-1 guidance and tailored study plans that can help you target those precise gaps with curated readings and AI-driven insights.

Organizing Citations and Final Bibliography

When it’s time to format your Works Cited or References, consistency matters. Decide whether you’ll use MLA, APA, or another citation style early and keep every source’s core fields complete: author, title, publication, year, pages, DOI/URL, and access date for online sources.

Before submission, run a quick checklist:

- Do all in-text citations match the bibliography entries?

- Are publication dates and page numbers correct?

- Are primary sources clearly distinguished from secondary interpretations?

Collaboration and Version Control

If you’re co-writing, use shared folders and version history (e.g., Google Docs, or file-sync services). Keep a changelog for major edits. This discipline reduces accidental overwrites and ensures your literature map evolves transparently.

Managing Time and Avoiding Burnout

Research can be overwhelming. Break the task into short, focused sessions: 45–60 minutes of active reading or note-taking, then a 10–15 minute break. Rotate tasks to avoid fatigue: one session for collecting sources, another for tagging and notes, another purely for writing.

When you’re stuck, consider scheduling a short 1-on-1 session with a tutor to get unstuck fast. Personalized coaching (like Sparkl’s tutoring) can help you clarify next steps, receive targeted feedback on outlines, and refine your thesis without losing momentum.

Common Pitfalls and How to Avoid Them

- Pitfall: Hoarding sources without reading.

Fix: Curate strictly and apply the 60-second rule. - Pitfall: Poor citation habits leading to missing references.

Fix: Log citations immediately in your reference manager. - Pitfall: Letting tags proliferate into chaos.

Fix: Standardize tag names and prune monthly. - Pitfall: Turning the literature review into a series of summaries.

Fix: Always synthesize — explain how sources relate to each other and to your question.

Real-World Example: Turning Three Sources into a Paragraph

Imagine three sources: a historical analysis showing wartime biography influences, a close reading arguing for fragmentation, and a comparative study linking imagery across authors. Here’s how you might synthesize them into one compact paragraph:

Scholars have linked the upheavals of wartime experience to shifts in narrative technique among British modernist poets, arguing that personal trauma foregrounded fragmentation as a stylistic response. (Historical analyses underscore the social context that produced these formal experiments.) Close reading of select poems reveals fragmentation not merely as aesthetic novelty but as a deliberate strategy to mirror dislocation. Comparative studies further suggest that similar imagery across different authors points to a shared cultural vocabulary rather than isolated innovation. Together, these lines of evidence indicate that modernist fragmentation functions both as a reflective technique and as a collective idiom, although fewer studies interrogate how publication conditions mediated these aesthetic choices — a gap this project aims to address.

Polish and Proofread Like a Pro

After drafting, step away for 24 hours if time permits. Return with fresh eyes and check for clarity, flow, and whether each paragraph genuinely synthesizes the literature. Read aloud to find awkward sentences. Get feedback from peers, teachers, or a dedicated tutor — an external perspective often spots logical leaps you can’t see.

Final Checklist Before Submission

- All citations present and formatted.

- Tables and figures labeled and referenced in text.

- Thesis remains central to each paragraph’s conclusion.

- Gaps and limitations are acknowledged (this shows maturity).

- Word count and formatting comply with AP or teacher requirements.

Wrapping Up: Organization as an Academic Muscle

Organizing sources is more than housekeeping — it’s an academic muscle you develop. The systems you build for note-taking, tagging, and synthesis will not only make your current AP literature review smoother, they’ll become tools you reuse in college and beyond. Start small, stay consistent, and iterate: a tiny habit like standardized file names or a weekly 30-minute note-prune session compounds into serious time savings and clearer thinking.

And remember: you don’t have to go it alone. When the research gets dense and deadlines loom, strategic help — whether a teacher’s feedback, a peer-review swap, or Sparkl’s personalized tutoring with tailored study plans and expert tutors — can clarify priorities and accelerate your progress without stripping away the learning you want to keep.

Next Steps You Can Take Today

- Create your project folder and name the first five source files consistently.

- Choose a reference manager and import your first 10 sources.

- Draft a one-page literature map that groups themes and lists three gaps to fill.

With a clear question, a simple folder system, disciplined note habits, and a synthesis-first attitude, your literature review will be organized, persuasive, and impressively professional. Good luck — and enjoy the process of turning a pile of readings into a story that only you can tell.

No Comments

Leave a comment Cancel