Why SAT Reading Passages Feel Different

If you’ve ever sat down with a school textbook and then tackled an SAT Reading passage, you probably noticed something odd: they don’t read the same. School texts often feel friendly, structured for learning, and supported by lectures, notes, or classroom discussion. SAT passages, by contrast, can feel dense, compact, sometimes old-fashioned, and occasionally intentionally tricky.

That feeling isn’t just in your head. The SAT’s Reading section is designed with a different purpose than a classroom text. While school readings are typically paired with teaching and repeated study, SAT passages are a timed, one-shot assessment that tests how well you can extract meaning, evaluate arguments, and use evidence under pressure.

Different goals, different design

Consider the purpose of each: a textbook might aim to teach, to build knowledge step by step, or to prepare you for applied problems. An SAT passage is designed primarily to assess a set of critical reading skills reproducibly across tens of thousands of students. That leads to predictable design choices—passages are curated for clarity, ambiguity where useful for testing inference, and a question set that probes specific cognitive skills.

Key ways SAT Passages Differ From School Texts

Below are the major differences, explained with examples and practical implications for how you should read.

1. Passage purpose: assessment vs. instruction

School texts often teach; SAT passages test. A chapter in a history textbook might introduce context, definitions, and examples to help you learn. A typical SAT passage brings a discrete piece of writing and asks you to draw conclusions from what’s written—not from what you already know or were taught.

Implication: On the SAT, the correct answer must be justified by explicit or strong implicit cues inside the passage. Outside knowledge is never required and often misleading.

2. Density and economy of language

SAT passages are tightly edited. Authors don’t waste words on scaffolding the way a teacher might. Every sentence has potential test value—setting up a tone shift, an evidentiary claim, or an inference question. That makes skimming dangerous and annotation valuable.

3. Author attitude and rhetorical structure matter more

In class, you may focus on facts and concepts. On the SAT, questions frequently ask about the author’s purpose, attitude, or function of a sentence. The test looks for your ability to identify shifts in tone, the role of a paragraph, or how evidence supports a claim.

4. Older, varied sources and styles

SAT readings draw from a wide range: classic literature, 19th-century essays, modern scientific exposition, and social science writing. That range intentionally exposes you to unfamiliar diction or argument structure—skills that measure adaptability rather than memorized content.

5. Controlled ambiguity and trap answers

Answer choices are designed to be tempting. They often include language that sounds right but isn’t fully supported by the passage. Recognizing these traps requires practice: you learn to hunt for the evidence sentence and to eliminate options that extend beyond the passage’s scope.

How These Differences Translate Into Reading Strategies

If SAT reading passages are different, your approach should be too. Here are practical adjustments that help you read like a test-taker, not like a student preparing for a literature quiz.

Strategy 1: Read for structure, not memorization

Instead of trying to memorize details on the first pass, map the passage. Identify the main idea, the author’s stance, and the function of each paragraph. A quick mental map—“para 1: sets context; para 2: refutes X; para 3: gives evidence”—saves time when questions ask where something is discussed.

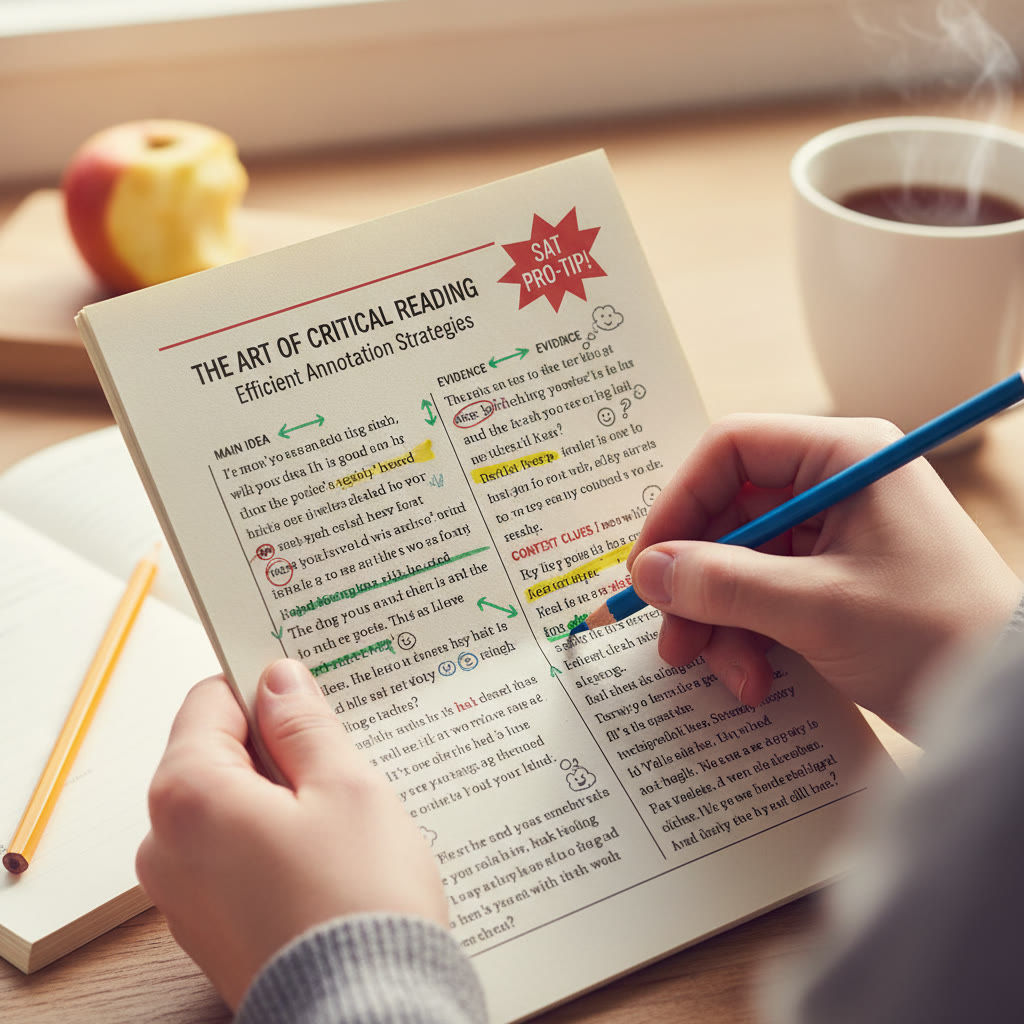

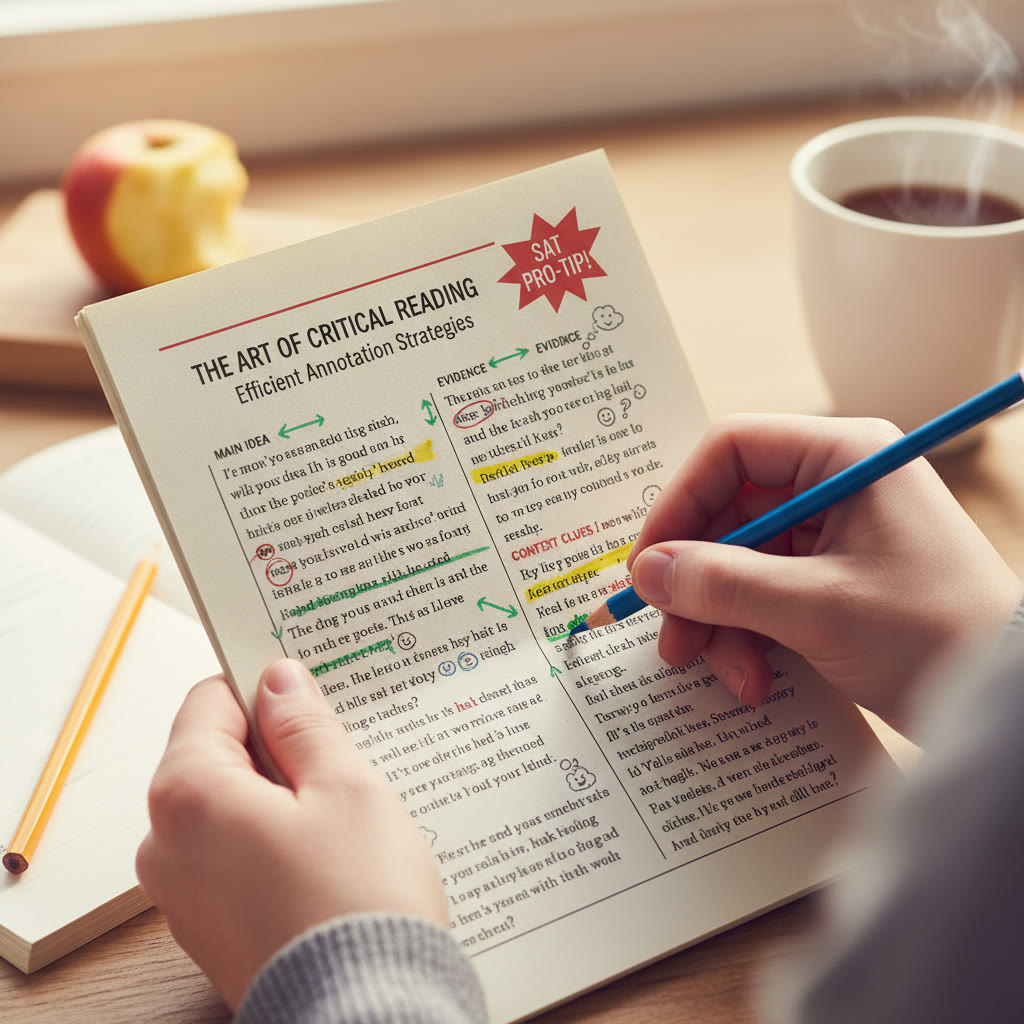

Strategy 2: Annotate with purpose

Don’t underline everything. Use short marks: a plus/minus for the author’s tone, a star for evidence sentences, and a bracket for contrasts or shifts. These tiny signals are efficient—on the SAT you want to mark cues that explicitly support likely question types, like evidence, main idea, or vocabulary-in-context.

Strategy 3: Read the question stem carefully

Many mistakes come from rushing into choices before fully understanding the question. Is it asking “according to the passage,” asking you to infer, or asking for the function of a sentence? That distinction changes your search behavior.

Strategy 4: Use line references smartly

When a question gives line numbers, go straight to those lines and read a few lines before and after. Many answer choices are ruled out by a small context window; conversely, some answers require seeing how the sentence functions in its paragraph.

Strategy 5: Practice evidence chaining

For questions that ask you to pair a claim with supporting evidence, practice the habit of stating the claim in your own words first, then scanning for the strongest supporting line. Avoid choosing an answer that feels right but is supported by a weaker or indirect line.

Strategy 6: Time management and triage

School readings allow re-reading over days. The SAT gives you one pass and limited time. Learn to triage: don’t get stuck on one hard question. Mark it, move on, and return if time permits. Successful students also learn to identify passages they can complete more quickly (for instance, some prefer science while others prefer literature).

Common Question Types — and What They Reveal About Passages

Understanding the kinds of questions you’ll face clarifies how passages are constructed.

- Main idea — Asks what the passage is about as a whole.

- Detail (line-referenced) — Requests information explicitly stated in the passage.

- Inference — Requires reading between the lines; supported by passage but not literally stated.

- Function — Asks why the author included a sentence or paragraph.

- Tone/attitude — Explores the author’s stance or emotional coloring.

- Evidence pairing — Demands selecting the line that best supports an earlier answer.

- Vocabulary in context — Tests your ability to interpret word meaning from surrounding text.

These question types push authors toward clear signalling devices—contrast words (however, yet), structural markers (first, finally), and emphatic sentences. A good reader learns to treat these signals as guideposts.

Side-by-side: SAT Passage vs. School Text — A Quick Comparison

| Feature | SAT Passage | School Text |

|---|---|---|

| Purpose | Assess critical reading skills | Teach or review a topic |

| Length | Short, concentrated (about 500–750 words) | Variable; often longer with sections for study |

| Language | Dense, sometimes archaic; every sentence may be functional | Explanatory, user-friendly; designed for gradual learning |

| Context provided | Minimal—passage must stand alone | High—lectures, headings, glossaries provide help |

| Assessment | Immediate, single exposure, timed | Formative—homework, projects, extended reading |

Examples: Read Differently, Answer Better

Let’s walk through a short, hypothetical illustration to make the differences concrete. Suppose a passage reads:

“In the mid-1800s, observers praised the efficiency of the new canal system; yet many local farmers regarded it with suspicion. Where some saw progress, others saw disruption. The debate, we now know, reflected not merely economic calculation but differing visions of what counted as community prosperity.”

Two question types you might see

- Detail: According to the passage, what did some local farmers think of the canal system? (Answer: They regarded it with suspicion.)

- Function: The phrase “Where some saw progress, others saw disruption” most nearly serves to — (A) contrast viewpoints; (B) summarize evidence; (C) introduce background; (D) predict outcomes. (Correct: A, contrast viewpoints.)

Notice how the SAT cares about the role a sentence plays—function—more than about long-term consequences or outside facts. If you treat the sentence as simply historical color, you might miss the functional question.

Why Classroom Habits Sometimes Hurt on the SAT

Certain good habits in school backfire under test conditions. Recognizing and adapting them helps.

Habit: Relying on memory or outside knowledge

In class you might connect a passage to something you already learned. On the SAT, outside knowledge can mislead you—answers must be grounded in the passage. If you introduce facts not in the text, you risk choosing an answer that the test writers intentionally made tempting.

Habit: Deep rereading of unclear phrases

In a classroom, you can spend time unpacking a difficult sentence. On the SAT, time is limited. Instead of agonizing over a single clause, annotate and move on—often the broader paragraph context clarifies what you need to answer questions.

Habit: Looking for thematic connections

Teachers encourage linking themes across materials. The SAT, however, isolates a passage intentionally. Resist the urge to impose outside themes; focus on what the passage itself prioritizes.

Practice Techniques That Mimic the Test

To internalize SAT-style reading, practice with intentionality. Below are effective exercises you can use on your own or with a tutor.

Timed passage drills

- Simulate test conditions: time yourself and work without notes for one passage and its questions.

- After finishing, review every missed question and write down the exact sentence that supports the right answer.

Evidence annotation

When you answer a question, underline the line that proves the choice. Over time this builds a habit of evidence-first reading, which combats traps and inference errors.

Paraphrase short paragraphs

Take each paragraph and rewrite it in one sentence. This forces you to focus on function and the paragraph’s role in the passage—skills the SAT rewards.

Vocabulary-in-context practice

- Pick 10 unfamiliar words from recent practice tests.

- For each, write the sentence in which it appears and infer the meaning from context before checking a dictionary.

- Notice how surrounding signals (contrast words, modifiers) point to the correct nuance.

How Targeted Tutoring Can Shorten the Learning Curve

Good practice is powerful, but targeted guidance accelerates progress. Tutoring can pinpoint which habits are classroom-driven and help you replace them with test-savvy strategies.

For example, Sparkl’s personalized tutoring focuses on 1-on-1 guidance, tailored study plans, expert tutors, and AI-driven insights to identify your weakest question types and create exercises that mimic real test pressure. That combination helps students move from repeating familiar school strategies to using SAT-specific reading techniques efficiently.

What effective tutoring emphasizes

- Diagnosis: Identifying whether mistakes come from timing, misreading, or misapplying outside knowledge.

- Skill-based drills: Focused practice on inferences, evidence pairing, and passage mapping.

- Feedback loops: Immediate explanations and corrections so wrong habits are addressed quickly.

Real-World Context: Why Colleges Care About These Skills

The SAT isn’t a relic; it claims to measure skills colleges value. Why? The reading section evaluates your ability to comprehend complex materials, analyze arguments, and use evidence—skills central to success in college-level courses across disciplines.

That’s why the test favors passages that force quick comprehension and clear evidence use. These are the everyday challenges of reading academic papers, dense policy reports, or primary-source documents in upper-level classes. Practicing SAT passages is, in a sense, practicing real-world academic reading under a deadline.

Putting It All Together: A 6-Step Game Plan

Use this concise routine when you sit down to practice, and during the test itself.

- 1) Skim purpose: read the first paragraph and topic sentences to get the author’s stance.

- 2) Map structure: note paragraph functions (context, evidence, counterargument).

- 3) Mark signals: annotate contrasts, emphases, and evidence sentences.

- 4) Tackle detail and line-referenced questions first: they’re often quickest.

- 5) For inference and function questions, return to the paragraph and paraphrase the relevant lines.

- 6) Flag hard questions and move on; return if time allows.

Final Thoughts: Embrace the Difference

The differences between SAT passages and school texts are intentional, not personal. The SAT asks that you adapt—shift from slow, layered learning to fast, structural reading. That shift is a skill, and like any skill, it gets easier with deliberate practice.

If you want to accelerate that adjustment, targeted support from a tutor can make a big difference. Tutors who understand the architecture of SAT passages can teach you how to spot signal phrases, build efficient annotations, and practice under realistic conditions. Programs like Sparkl’s personalized tutoring combine expert human feedback with AI-driven insights to hone those exact skills—helping you convert classroom habits into test-winning strategies without losing your natural reading instincts.

Remember: feeling uncomfortable with SAT passages at first is normal. Treat each practice passage as a short puzzle: identify the frame, find the evidence, and choose the answer the passage supports—not the one your prior knowledge prefers. Over time, the tight, purposeful language of SAT passages will start to feel like an ally instead of an obstacle.

Read deliberately, annotate smartly, and practice with purpose. The SAT Reading section rewards readers who know how to adapt—and that reader can be you.

No Comments

Leave a comment Cancel