Introduction: Why Artifacts Matter in AP Work

When students prepare for AP courses, exams, and particularly internally assessed or project-based components, the word “artifact” starts to pop up a lot. But what exactly is an IA-style artifact, and why might it matter to an AP student or their parent? In short, an IA-style artifact is any piece of work, document, recording, or material that you use as evidence to support an analysis, claim, or argument. Think of it as the tangible proof you bring to a discussion.

For AP students, artifacts can be a powerful bridge between classroom learning and assessment. They show that you don’t just understand concepts in theory — you can apply them, analyze them, and reflect on real materials. But not all artifacts are created equal. This guide walks you through what works, what doesn’t, and how to shape artifacts into clear AP-grade evidence that exam readers and teachers will respect.

What Do We Mean by “IA-Style” Artifact?

IA stands for “Internal Assessment” in many curricula (like IB), and the style of artifacts used there tends to emphasize original, contextualized, and analyzable materials. When we borrow the phrase “IA-style” for AP contexts, we mean artifacts that meet these criteria:

- Original or clearly sourced — you can trace where the data, image, or text came from.

- Contextual — the artifact has a clear relationship to the question or claim you’re making.

- Analyzable — it contains detail you can dissect (language choices, data trends, visual design, methodologies).

- Relevant to the AP rubric — it helps you meet the task (for example, supporting a rhetorical analysis, historical argument, or research claim).

Where Artifacts Fit into AP Assessments

AP courses and exams generally focus on mastery of content and skills: analysis, argumentation, synthesis, and evidence use. Some AP components (like AP Research, AP Seminar, or course projects) explicitly require or strongly reward external artifacts and multimedia evidence. Even in exam essays — whether a Document-Based Question (DBQ) in AP U.S. History or a rhetorical analysis in AP English Language — the idea is the same: your claims are stronger when grounded in concrete evidence.

So, for AP students, artifacts can function in three main ways:

- Primary evidence — original documents or firsthand data you analyze.

- Corroborative evidence — secondary materials that support and triangulate your argument.

- Illustrative evidence — artifacts that make abstract points vivid (images, charts, media clips).

What Works: Characteristics of Strong Artifacts

If you want your artifact to earn credit in an AP context, look for these attributes:

- Specificity: Narrow, concrete artifacts beat vague or general ones. A single political speech excerpt is better than a vague idea of “a speech.”

- Relevance: It must directly support the analytical claim you make. Don’t shoehorn the artifact into a loose connection.

- Traceability: You should be able to say who created it, when, and why (or at least speculate intelligently with evidence).

- Rich detail: The artifact should offer layers of meaning: language choices, visuals, data points, or methodology you can interrogate.

- Context provided by you: A great artifact still needs explanation. Explain beneath the surface — don’t assume the grader sees the connection.

Examples of Strong Artifacts

- A scanned primary source (letter, diary entry, short government memo) used in a DBQ-style analysis.

- A dataset from a local survey you conducted, with raw numbers and a brief methodology note, used in AP Research.

- A public speech excerpt with rhetorical devices annotated, used in AP English Language analysis.

- A short video clip (described textually in your submission) showing an experiment’s procedure for an AP Science project, accompanied by controlled data tables.

What Doesn’t Work: Common Pitfalls with Artifacts

Students often assume more artifacts equal stronger work. That’s not true. Quality trumps quantity. These common mistakes undermine the usefulness of artifacts:

- Irrelevance: Bringing in an impressive document that doesn’t actually support your thesis.

- Poor sourcing: Artifacts that can’t be traced back or that have ambiguous authorship are risky.

- Surface description only: Summarizing rather than analyzing — graders want interpretation and linkage to claims.

- Overreliance on tertiary summaries: Using an encyclopedia-style overview instead of primary or close secondary sources.

- Unclear selection criteria: If you can’t justify why you chose an artifact, readers will question its weight.

Real-World Examples of Poor Artifact Use

Imagine a student attaches a broad newspaper front page and writes “this shows public concern about X.” That’s weak: the student needs to point to a headline, an editorial voice, a data chart, or a headline placement choice and explain how that conveys public concern. Likewise, attaching a random website screenshot without provenance is a red flag.

Practical Steps to Turn an Artifact into AP-Quality Evidence

Turning a raw piece of material into useful evidence is a skill. Here’s a step-by-step checklist you can follow.

- 1. Select with intention: Ask, “How does this artifact advance my claim?” If you can’t answer in one sentence, choose another artifact.

- 2. Record provenance: Note the creator, date, location, and purpose (or give a reasonable, evidence-based inference).

- 3. Contextualize briefly: Situate the artifact — what was happening historically or socially, or what was the experiment’s setup?

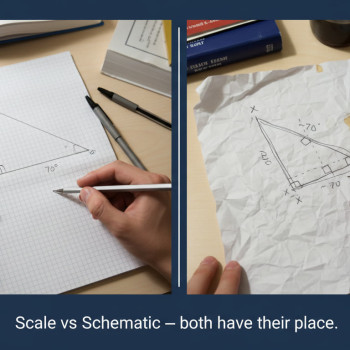

- 4. Analyze the details: Break it down. For documents: tone, diction, rhetorical strategies. For data: trends, outliers, sample size. For images: composition, framing, symbols.

- 5. Link explicitly: Tie each analytical point back to your thesis or research question — don’t leave the connection implicit.

- 6. Reflect on limitations: Acknowledge biases, gaps, or uncertainties in the artifact. Good scholars show nuance.

How to Present Artifacts in Different AP Contexts

Different AP courses and tasks reward different kinds of artifacts. Below is a practical guide for where certain artifact types shine.

| AP Context | Artifact Types That Work | How to Use It |

|---|---|---|

| AP Research / Seminar | Original survey data, interview transcripts, small datasets, project photos | Present methodology, show raw results, analyze limitations, triangulate with literature |

| AP English Language | Speech excerpts, op-eds, advertisements, photographs | Annotate rhetorical devices, audience appeals, rhetorical strategies, and effect |

| AP History (DBQ-style) | Primary documents, maps, political cartoons, statistics | Source analysis (author, purpose, bias), corroboration, and period context |

| AP Science Projects | Experimental logs, images of apparatus, raw measurement tables | Document controls, error analysis, repeatability and visual evidence |

Annotation and Presentation Tips

How you present an artifact can be as important as which artifact you choose. Use clear labels, brief captions, and targeted annotations so graders can see why each artifact matters.

- Put a concise caption: who/what/when/why in one line.

- Use numbered annotations to point to exact lines, data points, or visual elements you reference in the text.

- When submitting digital artifacts, ensure legibility: crop, increase contrast, and include a short transcript for audio or video excerpts.

- Always tie back to the rubric or assessment task — show how the artifact helps you hit a scoring criterion.

Ethical and Practical Considerations

Artifacts often involve other people’s work, sensitive data, or copyright issues. Respect privacy and academic integrity:

- Obtain consent for interviews or images of people when required.

- When using published materials, cite sources clearly (even if your teacher doesn’t require formal citations).

- Be transparent about modifications (e.g., if you cropped or anonymized data).

- Protect personal data — anonymize responses from human subjects unless you have explicit permission.

Example Walkthrough: From Artifact to AP-Ready Paragraph

Let’s turn a concrete example into an AP-quality paragraph. Suppose you’re writing an AP English Language analysis and you include an editorial cartoon criticizing social media. Follow these moves:

- Select: Choose a cartoon with clear symbols (e.g., a smartphone depicted as a puppet master).

- Provenance: Note the cartoonist, publication, and date.

- Context: Mention a contemporary event that makes the cartoon timely.

- Analyze: Identify visual metaphors (puppet strings), tone (satirical), and audience (readers critical of tech culture).

- Link: Connect these observations to your thesis about media manipulation and rhetorical strategy.

- Limit: Acknowledge that a cartoon simplifies complex issues — then show why it still provides persuasive evidence.

That set of moves converts a simple image into concrete, gradeable evidence.

Quick Checklist: Is This Artifact AP-Ready?

- Can I state its creator, date, and original purpose?

- Does it have details I can analyze beyond summary?

- Does it clearly support a claim in my argument or research question?

- Have I noted limitations and potential biases?

- Is it presented legibly and with concise captions/annotations?

How to Practice Artifact Use — Study Activities

Like any skill, analyzing artifacts gets better with deliberate practice. Here are a few short exercises you can use alone or with a study partner:

- Take a primary-source paragraph and annotate five rhetorical or rhetorical-like choices (word connotations, syntax, evidence use).

- Turn a small dataset into two different claims — one supported, one contradicted — then explain why the evidence supports one interpretation over the other.

- Swap artifacts with a peer and write a 200-word analysis of theirs within 30 minutes; then compare notes and critique each other’s linking to thesis.

How Tutoring Can Help — Subtle, Strategic Support

Working with a tutor can speed up this learning curve. Personalized tutoring — like Sparkl’s 1-on-1 guidance — can help students identify strong artifacts, design experiments or surveys for AP Research, and practice precise analysis under exam conditions. Expert tutors can give tailored study plans, model artifact annotation, and offer AI-driven insights to track progress and refine selection strategies. The goal isn’t dependence — it’s accelerating independent skills so students produce sharper, better-evidenced work on their own.

Common Questions From Students and Parents

Q: How many artifacts should I include?

A: Less is more. Include enough to triangulate your claims (two to four strong artifacts is often better than a pile of weak ones). Quality, relevance, and depth of analysis matter more than quantity.

Q: Can artifacts be multimedia?

A: Yes. Audio clips, video excerpts, and images can be powerful. But always supply transcripts or descriptions so readers who can’t access the media still see your evidence and analysis.

Q: What about student-created artifacts?

A: Original student work can be excellent evidence — surveys you ran, experiments you performed, creative projects you produced. Just document your methodology and include raw data or drafts that show your process.

Q: How do teachers and graders view edited or redacted artifacts?

A: Minor edits for clarity (cropping, contrast adjustments, anonymization) are acceptable if you disclose them. Large edits that change meaning undermine trust. Transparency is key.

Final Thoughts: Make Artifacts Work for You

Artifacts are not props — they are the scaffolding of sound academic argument. When selected and presented carefully, IA-style artifacts bring your AP work from abstract claims to persuasive, evidence-backed conclusions. Start by choosing artifacts that are specific, traceable, and rich in analyzable detail. Then practice the skill of close explanation: annotate, link to your thesis, and acknowledge limitations. Use checklists and peer review to sharpen your selections, and consider targeted tutoring or coaching if you want faster progress. Sparkl’s personalized tutoring and tailored study plans can be especially helpful if you’re aiming to elevate artifact selection and analysis quickly and confidently.

At the end of the day, artifacts give your voice credibility. They show that you can see details, weigh evidence, and reason clearly — the very skills AP exams look for. With a little planning, deliberate practice, and honest reflection, your artifacts won’t just be appendices; they’ll be the beating heart of stronger, more convincing AP work.

Quick Reference: Artifact Do’s and Don’ts

- Do: Choose specific, analyzable pieces; provide provenance; annotate and link to claims.

- Don’t: Use vague or irrelevant materials; assume the reader sees the connection; hide edits or provenance gaps.

Good luck — and remember: an artifact is only as strong as the thinking you bring to it. Practice the moves above, and your evidence will start earning the scores it deserves.

No Comments

Leave a comment Cancel