Why Claim–Evidence–Reasoning Is the Secret Weapon for AP FRQs

If you’ve stared at a blank free-response question (FRQ) on an AP exam and felt your brain go fuzzy, you are far from alone. FRQs reward clear thinking, organization, and the ability to connect facts to scientific or historical reasoning — not flashy prose. That’s where the Claim–Evidence–Reasoning (CER) frame becomes invaluable. It’s simple, repeatable, and fits almost every AP subject that asks you to make an argument: science, history, economics, psychology, environmental science, and more.

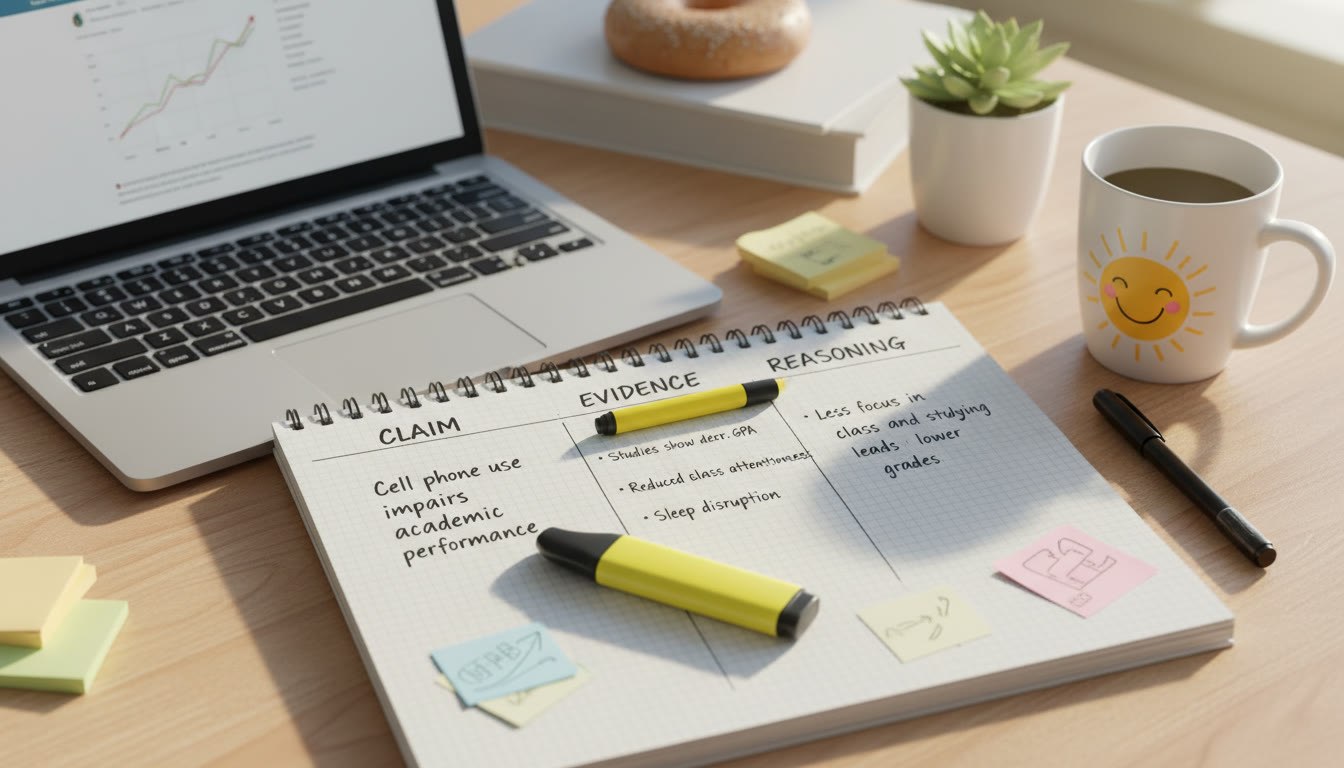

Think of CER as a three-part checklist you can write under pressure. First, make a concise claim. Second, back it with concrete evidence. Third, explain why that evidence supports the claim using disciplinary reasoning. Do that reliably, and exam readers will find what they’re looking for — and award points.

The three parts, explained in plain English

- Claim: One-sentence answer to the prompt. Direct and specific. No hedging.

- Evidence: Two or more pieces of concrete, relevant data or facts from the prompt, passage, experiment, or your course content.

- Reasoning: The bridge that links evidence to claim — why the evidence matters, showing your understanding of concepts, mechanisms, or historical causation.

How CER Maps to AP Rubrics

Across AP exams, rubrics reward three things: accuracy of content, use of appropriate evidence, and demonstration of reasoning or causal explanation. CER mirrors that structure. When you write in CER form, you’re almost writing directly to the rubric — which raises your chance of scoring top marks.

Quick comparison: CER vs. a typical rubric

| Rubric Criterion | What Examiners Want | How CER Delivers |

|---|---|---|

| Direct Answer | A clear, unambiguous response to the prompt | The Claim is a one-sentence, direct answer |

| Supporting Evidence | Relevant facts, data, or examples | Evidence section lists and cites concrete items |

| Use of Reasoning | Explanation of the connection between claim and evidence | Reasoning explicitly ties mechanism, principle, or causation to the evidence |

Step-by-step: Writing a CER FRQ in 15–20 Minutes

Timing matters. Many AP FRQs expect a high-quality paragraph or two in a constrained time window. Here’s a practical workflow you can practice so it becomes muscle memory on test day.

0–2 minutes: Read the prompt smartly

- Skim the entire prompt to find the question and any attached data, figures, or quotes.

- Identify the task verb — explain, justify, describe, evaluate — and highlight it. This tells you how deep your reasoning needs to be.

2–4 minutes: Draft your Claim

- Write a one-sentence claim that directly answers the prompt. Keep it specific: avoid “I think” or long preambles.

- If the question asks to choose between two options, state the chosen option and the short reason.

4–10 minutes: Pull Evidence

- Scan given materials and your memory for 1–2 strong, relevant pieces of evidence. In math or statistics FRQs, evidence may be a numerical result; in history, a primary source or event; in science, a data point or trend.

- Write the evidence clearly. If using numbers, include units and significant figures as appropriate.

10–18 minutes: Write the Reasoning

- Explain how the evidence supports the claim. Use course concepts — laws, mechanisms, cause-and-effect chains, historical context, or experimental design language.

- Be concise but specific. Tie back to the rubric’s expected content.

18–20 minutes: Quick polish

- Reread for clarity and to ensure you didn’t omit a required component.

- Add labels like “Claim:” “Evidence:” “Reasoning:” if your handwriting looks messy — clarity helps graders find points fast.

Examples: CER in Action (Three Mini-FRQs)

Seeing CER used across different AP subjects clarifies how flexible the frame is. Below are three short examples. Each shows how the same structure works in science, history, and psychology.

Example 1 — AP Environmental Science (Data prompt)

Prompt summary: A graph shows increased nitrate levels downstream from agricultural fields over 20 years. Explain whether agricultural runoff is the likely cause.

Claim: Agricultural runoff is the likely cause of the increased nitrate levels downstream.

Evidence: The graph shows nitrate concentrations rising from 2 mg/L to 8 mg/L between Year 1 and Year 20; the timing of the increase aligns with a documented expansion of fertilizer application in Year 3. Upstream sampling shows consistently low nitrate levels, suggesting a local source near the agricultural area.

Reasoning: Nitrate is a common component of synthetic fertilizers; increased application increases soluble nitrate in soils that can be mobilized by rainfall and enter waterways through surface runoff and leaching. The temporal correlation between fertilizer expansion and nitrate rise, together with low upstream concentrations, supports a causal link rather than a regional atmospheric source.

Example 2 — AP U.S. History (Document-based prompt)

Prompt summary: Using two documents, argue whether the 1920s economic growth benefited all groups equally.

Claim: The economic growth of the 1920s did not benefit all groups equally.

Evidence: Document A (factory output data) shows rapid industrial growth and increased corporate profits. Document B (a first-person account from a sharecropper) describes stagnant wages and debt in rural areas. Employment statistics show high unemployment rates for African Americans in urban centers despite overall GDP growth.

Reasoning: Economic expansion concentrated in industrial sectors produced jobs and profits but did not translate into equitable income distribution. Structural barriers like segregation, discriminatory hiring, and sharecropping systems prevented marginalized groups from accessing the gains of industrial growth, explaining the contrasting experiences reflected in the documents.

Example 3 — AP Psychology (Experimental prompt)

Prompt summary: A study found that participants who slept 8 hours after learning a word list recalled more words than those who stayed awake.

Claim: Sleep improves memory consolidation, which likely caused better recall in the 8-hour sleep group.

Evidence: The experimental results show mean recall of 18 words for the sleep group versus 11 words for the awake group, with similar learning-phase scores. The study controlled for initial encoding by giving both groups the same study time and material.

Reasoning: Research on memory systems suggests that sleep, particularly slow-wave sleep, facilitates hippocampal replay and consolidation into long-term storage. Because initial encoding was controlled and both groups began with comparable learning, the difference in recall plausibly reflects consolidation benefits from sleep rather than encoding variability.

Common CER Mistakes and How to Avoid Them

- Vague Claims: Avoid nonspecific phrases like “might be” or “could be.” Make a clear assertion.

- Weak Evidence: Don’t use generic facts. Tie evidence directly to the prompt or provided material.

- Insufficient Reasoning: Don’t assume the connection is obvious. Explain the mechanism or causal link explicitly.

- Over-quoting the Prompt: Use the prompt as a source, but synthesize — graders credit your reasoning, not repetition.

Practice Routines That Reinforce CER

Repetition with feedback is the fastest route to fluency. Here are practice routines you can incorporate into weekly study sessions.

- Daily 10-Minute Micro-FRQs: Pick a short prompt from past exams or practice books and write a CER paragraph in 10 minutes.

- Evidence Inventory: For each unit, create a two-column list of key facts/data and the course concept each supports. This makes evidence retrieval faster under pressure.

- Peer Review Swap: Exchange FRQs with a classmate, grade each other using the rubric, and discuss one improvement each.

- Timed Full-Length Drills: Once a week, simulate exam conditions for complete FRQs and review with the scoring guide.

How a tutor can speed this up

Working with a tutor — especially one who gives targeted feedback on your Reasoning paragraphs — helps spot repeated logical gaps and accelerates improvement. Personalized programs like Sparkl’s 1-on-1 guidance and tailored study plans focus your practice on weak spots and use AI-driven insights to highlight which types of evidence you miss most often.

Using CER on Data-Heavy Prompts

Some FRQs come with graphs, tables, or experimental data. Your job is to extract the smallest set of accurate, relevant pieces of data that directly support the claim, then interpret them with precision.

Checklist for data prompts

- Label axes and units if they’re not clear to you.

- Quote specific numbers or trends (e.g., “a 45% decline” or “a clear negative correlation”).

- State any assumptions you must make and why they’re reasonable.

- Explain anomalies if the data show them — graders reward thoughtful nuance.

Scoring Examples: How CER Wins Points

Below is a compact example of how an examiner’s checklist maps to the CER parts so you can see where points are earned. Use this as a mental rubric during the exam.

| Scoring Item | What Earns the Point | Where to Put It (CER) |

|---|---|---|

| Direct response | Clear statement that answers the prompt | Claim |

| Relevant supporting facts | Two or more correct, specific pieces of evidence | Evidence |

| Use of principle | Application of course concept or mechanism to the evidence | Reasoning |

| Coherence and clarity | Logical flow that connects claim, evidence, and reasoning | Across the CER paragraph |

How to Customize CER for Different AP Subjects

CER is flexible. The way you reason will differ by discipline, but the frame stays the same. Here are a few tailoring tips:

- AP Biology / Environmental Science: Reasoning should cite mechanisms (e.g., photosynthesis, nutrient cycling) and experimental controls.

- AP Chemistry / Physics: Reasoning leans on laws, equations, and cause-effect relationships; include units and significant figures in evidence.

- AP U.S. History / European History: Reasoning emphasizes causation, continuity and change, and the significance of context; use primary sources as evidence.

- AP Psychology: Reasoning often references cognitive or behavioral mechanisms and empirical study designs.

- AP Statistics: Use numerical evidence with appropriate interpretation: significance, margin of error, and practical implications.

Model Answers vs. CER: Why You Should Practice Both

Model answers show what high-scoring responses look like, but merely memorizing them is a trap. CER trains you to build original, test-specific responses that satisfy rubrics consistently. Practice by reading model answers, then deliberately rewriting them into compact CER paragraphs. This develops both content and exam-ready structure.

When to Add Extra Depth (and When Not To)

There’s a balancing act between thoroughness and clarity. On an AP exam, adding irrelevant detail wastes time. Use this rule of thumb: if a sentence doesn’t strengthen your claim or explain your evidence, skip it. If the prompt asks for evaluation or trade-offs, add one short paragraph weighing alternatives — but keep it clearly tied to CER.

Customizing Practice With Sparkl’s Personalized Tutoring

Everyone’s weak point is different: maybe you can find evidence fast but struggle to articulate reasoning, or you have the ideas but not the exam pacing. That’s where targeted 1-on-1 work helps. Sparkl’s personalized tutoring pairs you with expert tutors who offer tailored study plans, targeted FRQ drills, and feedback loops that focus on reasoning clarity. Their use of AI-driven insights also helps flag recurring gaps in your evidence selection and logic so you can fix patterns, not just single mistakes.

Final Checklist: CER Before You Turn the Page

- Claim: Single clear sentence that answers the prompt.

- Evidence: Two specific, relevant facts, data points, or citations.

- Reasoning: Explicit link showing how evidence supports the claim and which course concept is at work.

- Formatting: Label sections if needed; use numbers or bullets for clarity in multi-part responses.

- Time: Reserve the last 2 minutes to re-read and fix any small errors.

A Short Practice Prompt You Can Try Right Now

Prompt: A provided graph shows atmospheric CO2 concentration rising steadily over 60 years while average local plant biomass in a study area fluctuates with a slight upward trend. Using the CER frame, explain whether increased CO2 alone accounts for the biomass change.

Set a timer for 12 minutes and write a CER paragraph. Then compare your answer against the checklist above: direct claim, two pieces of evidence, and explicit mechanistic reasoning. If you want feedback, consider sharing drafts with a teacher or a Sparkl tutor for focused review.

Closing Thoughts: Make CER Second Nature

Claim–Evidence–Reasoning is not a trick. It’s a study-hall-tested, classroom-approved way to organize your thinking so graders — who spend seconds scanning an answer — can find the substance quickly. The more you practice the CER routine, the faster and more precise your FRQ answers will become.

Start small: one CER paragraph per day. Build up to timed sections. Get feedback, correct your recurring issues, and keep a running list of effective evidence you can call on during the exam. With structure, deliberate practice, and a little help when needed, CER can transform FRQs from stressors into predictable opportunities to show what you know.

Good luck — and remember: clarity beats complexity every time. When in doubt, make a claim, back it up, and explain why it matters.

No Comments

Leave a comment Cancel