Introduction: Why Artist and Researcher Identities Matter for AP Students

There’s a quiet revolution happening in AP classrooms across the country: students are no longer satisfied with simply memorizing facts or mimicking techniques. Whether you’re in AP Art and Design, AP Research, or combining creative work with academic inquiry, the heart of exceptional work is an identity — a clear sense of who you are as an artist and a researcher and how those roles feed each other. This blog is for the student who wants to do more than check boxes for a score. It’s for the student who wants to leave college admissions officers—or portfolio reviewers—with a memorable, authentic impression.

What Does It Mean to Have an Artist/Researcher Identity?

At first it sounds fancy, but identity here is practical. It’s a set of habits, questions, aesthetic preferences, and research methods that guide your decisions. Think of it as your creative fingerprint: the themes you return to, the visual language you prefer, and the way you ask questions and test ideas. For AP students, this identity helps make work consistent, defensible, and memorable—qualities that matter in AP portfolio assessments, research papers, and college applications.

Two Roles, One Voice

An artist experiments with form, color, composition, and emotion. A researcher interrogates sources, methods, evidence, and interpretation. Combined, they let you make art that is informed and inquiry that is imaginative. You’re not just illustrating what you already know—you’re using research to push your art into new territories, and using art to communicate complex ideas more powerfully.

Examples of Artist/Researcher Identity in Action

- A student exploring urban ecology creates prints using pollen and pollutants collected from different neighborhoods, then uses local air-quality data to map patterns in the portfolio statement.

- An AP Research candidate studies cultural memory, conducting interviews and archival work, and translates the findings into a mixed-media series that layers text fragments and family photographs.

- A ceramics student tests clay bodies and glazes, documents each firing, and writes a reflective research component that ties material experiments to historical ceramic practices.

How to Find Your Angle: Practical Steps

Finding your angle is a process, not a single moment of inspiration. Below are deliberate steps you can practice—like exercises to train a skill—so your artistic and research voice grows reliably.

1. Start with Curiosity Prompts

Curiosity prompts are short questions that pull you toward a theme. Keep a running list in your phone or sketchbook. Examples:

- What object or place catches my attention repeatedly?

- Which historical moment or local story do I want to surface?

- What material frustrates me—or excites me—when I try it?

Pick one prompt and commit to exploring it for two weeks. The goal is not to finish something perfect but to discover what keeps your attention.

2. Combine Small Research Projects with Small Art Projects

Short cycles of research + making build momentum. Try a two-week micro-project: spend the first week gathering data, interviews, or source material; spend the second week producing a small body of work informed by that research. Document the process—photos, notes, quick reflections—for your AP portfolio or research paper appendix.

3. Make Constraints Your Friend

Constraints force decisions and reveal style. Limit your palette to three colors, your camera to one lens, or your research to a single newspaper archive. Constraints help you see patterns and develop a recognizable voice.

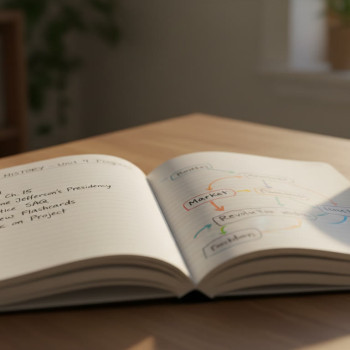

4. Keep a Process Journal

Write down decisions and why you made them. A process journal is invaluable when you need to write portfolio statements or the AP Research Academic Paper. Capture failures as well as successes—sometimes a failed experiment becomes your signature approach.

Balancing Technical Skill and Conceptual Depth

AP graders and portfolio reviewers look for evidence of technical skill and the ability to meaningfully engage with content. Technical skill without concept feels hollow; concept without craft can’t deliver your idea.

Techniques for Building Both

- Set technical goals (e.g., master chiaroscuro, learn to use the kiln) and conceptual goals (e.g., interrogate identity in a series of five works) for each semester.

- Alternate practice routines with reflective sessions—practice three hours of technique, then spend an hour writing about what the technique enables conceptually.

- Use critique cycles: present technical attempts and conceptual sketches to peers and teachers, then revise with targeted objectives.

Mapping Your Portfolio and Research Paper

Whether your AP pathway requires a visual portfolio (AP 2-D, 3-D, or Drawing) or a full AP Research submission, the structure should reflect a coherent identity. Below is a simple table to help you plan components you should include and how they support your identity.

| Component | What It Shows | How It Supports Identity |

|---|---|---|

| Series of 4–6 Works | Development of a theme and consistent choices | Demonstrates sustained inquiry and aesthetic coherence |

| Process Documentation | Photos, tests, notes, drafts | Shows method, experimentation, and reflection |

| Research Appendix/Annotated Bibliography | Sources, interviews, data | Provides context and credibility to conceptual choices |

| Artist Statement / Academic Abstract | Summarizes aims and outcomes | Communicates your angle crisply and persuasively |

| Technical Experiments | Material and method tests | Evidence of craft and problem-solving |

Writing About Your Work: Clarity Over Jargon

Strong statements are clear and specific. Avoid empty phrases like “explores identity” without context. Instead, identify the specific aspect of identity or the concrete question you are asking, and explain how your methods answer it.

Quick Template for an Artist Statement

Use this as a starting point and make it your own:

- One-sentence summary of the project’s focus.

- Two sentences about the methods and materials used.

- One sentence about what you discovered or how viewers should engage with the work.

Example: “This series investigates the acoustic memory of my neighborhood by collecting and visualizing ambient sound patterns. Using field-recording techniques and mixed-media notation, I translate audio data into monochrome prints. The work asks viewers to consider how everyday soundscapes inform personal and communal memory.”

Making Your Research Rigorous and Relevant

AP Research requires methodological rigor. Use clear questions, appropriate methods, and thoughtful interpretation. Even if you’re in an arts-focused AP pathway, adding a small, well-designed study (surveys, interviews, archival searches) gives your work weight.

Design Tips for Small-Scale Research

- Define a narrow, answerable question.

- Choose methods that match the question—qualitative interviews for lived experience, quantitative counts for pattern analysis.

- Document sources meticulously so you can cite them in an appendix or bibliography.

- Reflect on limitations—every study has them. Acknowledging them makes your conclusions stronger, not weaker.

Time Management: Building Work Without Burnout

Balancing AP classes, extracurriculars, and life requires realistic rhythms. Instead of marathon sessions, adopt sustainable routines that allow deep work and rest.

Weekly Rhythm Example

- Monday — Planning and short research reading (60–90 minutes)

- Tuesday — Technical practice (90 minutes)

- Wednesday — Studio making (2 hours)

- Thursday — Reflection and documentation (60 minutes)

- Friday — Peer critique or mentor check-in (60 minutes)

- Weekend — Dedicated block for a longer session (3–4 hours) with breaks

Short, consistent sessions beat frantic all-nighters—especially for creative work where repeated exposure improves judgment.

Critique Culture: Receiving and Using Feedback

Critique is an essential part of developing a strong identity. Approach feedback as a testing tool: not everything should change, but everything should be considered.

How to Use Feedback Productively

- Record the critique: take notes or audio record with permission.

- Sort suggestions into categories: immediate fixes, experimental ideas, and long-term reflections.

- Test one or two suggestions at a time rather than overhauling everything.

Tools and Technologies That Amplify Your Work

From scanners and DSLR cameras to data visualization tools and transcription apps, the right tech can help you document, analyze, and present your work. Don’t feel pressured to master every tool; learn what supports your angle.

Starter Tech Stack

- A reliable camera or smartphone with manual controls for documenting work

- A note-taking app or analog sketchbook for process logs

- Basic audio recorder for interviews or field recordings

- A spreadsheet or simple visualization tool for organizing research data

How Personalized Tutoring Can Accelerate Your Identity Work

Developing a distinct artist/researcher identity benefits from mentorship. Personalized tutoring—like the tailored support offered by Sparkl—can accelerate progress by providing 1-on-1 guidance, targeted study plans, and expert feedback. Tutors help you break down large goals into practical steps, recommend focused readings and experiments, and give candid critique when you most need it.

When to Consider Tutoring

- If you’re stuck choosing a theme or narrowing a research question.

- If you need structured time and accountability to finish a portfolio or research draft.

- If you want expert input on improving technical skills or refining methodology.

Sparkl’s personalized approach pairs students with tutors who understand both art practice and academic research, providing AI-driven insights and progress tracking to keep your work focused and portfolio-ready.

Real-World Contexts to Inspire Projects

Connecting your work to place, history, or current events can give it depth and relevance. Consider these entry points:

- Local histories and oral archives: interview elders, visit local historical societies.

- Environmental data: map weather, pollution, or biodiversity and translate data into visual forms.

- Community rituals and events: document participatory practices and reflect on their meaning.

Example Project Roadmap: “Echoes of Market Street”

Concept: Investigate how a local marketplace has changed over time and how that shapes neighborhood identity.

- Week 1–2: Archival images and oral histories (research).

- Week 3–4: Material collection—receipt fragments, flyers, fabric swatches (making).

- Week 5–6: Create a mixed-media series that layers found materials and mapped timelines (production).

- Week 7: Write a 500–700 word artist statement that ties findings to visual choices (reflection).

Assessment Prep: Translating Process Into Scores

AP submissions and portfolio reviewers want to see evidence of sustained inquiry, technical skill, and reflection. Use your process documentation to show growth over time—progression is often as compelling as a single strong piece.

Checklist for Final Submission

- Clear thematic coherence across works.

- Process documentation showing iteration and experiments.

- Concise artist/researcher statement (specific, evidence-based).

- Annotated bibliography or research appendix if applicable.

- High-quality images of work with consistent lighting and framing.

Common Pitfalls and How to Avoid Them

Students often make similar mistakes when forging an identity. Here’s how to sidestep them.

Pitfall 1: Scattered Themes

Fix: Narrow focus and use constraints. Better to deeply explore one idea than superficially touch many.

Pitfall 2: Overreliance on Jargon

Fix: Explain complex ideas plainly. Use specific examples from your work to show, not tell.

Pitfall 3: Inadequate Documentation

Fix: Schedule brief documentation sessions immediately after experiments. Photos and short notes are gold.

Next Steps: Plan for the Next 3 Months

Create a three-month plan with weekly milestones. Here’s a sample blueprint to help you move from idea to portfolio-ready work.

| Month | Focus | Milestones |

|---|---|---|

| Month 1 | Exploration and Research | Generate 15 curiosity prompts, choose one, complete a 2-week research sprint, begin process journal |

| Month 2 | Experimentation and Making | Create 8–10 small studies, document each, select best 4–6 for series |

| Month 3 | Refinement and Presentation | Finalize 4–6 works, write artist/researcher statement, mock critique, prepare submission images |

Final Thoughts: Your Angle Is a Practice

Finding your artist/researcher identity isn’t a one-time achievement; it’s a practice that grows more precise over time. The strongest identities are the product of curious questions, disciplined experiments, and thoughtful reflection. Keep records, seek feedback, and design projects that both challenge you and resonate with your lived experience.

If you want tailored feedback, targeted practice plans, or help turning messy process notes into polished statements, consider the targeted support of personalized tutoring. With 1-on-1 guidance, tailored study plans, and expert tutors who understand both craft and research, you can refine your angle faster and with greater confidence—so your AP submission, portfolio, or research paper truly represents you.

Parting Prompt

Before you go: write a single sentence that answers this question—What is one question I keep returning to, and how can a single small project help me explore it? Use that sentence as your north star for the next two weeks.

Good luck. Keep experimenting, keep documenting, and trust that your angle will emerge as you do the work.

No Comments

Leave a comment Cancel