Why Logical Fallacies Matter for AP Students

If you’ve ever stared at a blank AP essay prompt or felt your argument crumble under a teacher’s question, you’re not alone. Writing a convincing argument isn’t just about having a strong opinion — it’s about building a line of reasoning that stands up to scrutiny. Logical fallacies are the little cracks in reasoning that can undermine even a passionate, well-informed point of view. For AP students, where clarity, evidence, and analysis earn points, avoiding fallacies is essential.

What Is a Logical Fallacy?

In plain terms, a logical fallacy is a flaw in reasoning. It’s a place where your argument moves from evidence to conclusion in a way that isn’t logically valid or that relies on faulty assumptions. Fallacies can be accidental — the product of rushed thinking — or persuasive techniques that intentionally mislead. Either way, they weaken your essays, class discussions, and exam responses.

Common Fallacies You’ll See (and Why They Hurt Your Score)

Below are the most frequent fallacies students make in AP-level writing and discussion. For each, you’ll find a quick definition, a short AP-relevant example, why it’s problematic, and a simple strategy to avoid it.

| Fallacy | Quick Definition | AP-Style Example | How to Avoid It |

|---|---|---|---|

| Straw Man | Misrepresenting an opponent’s position to make it easier to attack. | Claiming a source argues to “ban all technology” when the source argues for regulation. | Quote accurately; address the strongest version of the opposing view. |

| Ad Hominem | Attacking the person instead of the argument. | Dismissing a study because the researcher is young rather than critiquing methods. | Focus on evidence and reasoning, not the author’s traits. |

| False Cause (Post Hoc) | Assuming causation from mere sequence or correlation. | Arguing that increased test scores came solely from one new policy without considering other variables. | Look for alternative explanations and cite controlled evidence. |

| Hasty Generalization | Drawing a broad conclusion from limited evidence. | Basing a claim about an entire school year from one class’s experience. | Use representative samples and acknowledge limits of evidence. |

| Appeal to Authority | Relying on authority rather than argument or data. | Using a celebrity quote as proof of scientific fact. | Prefer primary evidence and explain why an authority’s expertise matters. |

| False Dilemma | Presenting only two options when more exist. | Saying “Either we cut arts or academic programs must suffer” without exploring alternatives. | Map the range of possibilities and address middle grounds. |

How Fallacies Show Up in AP Exams

Different AP subjects demand different argumentative styles. Recognizing how fallacies appear across contexts helps you adapt your strategy.

AP English Language and Composition

Here the score depends on clarity of claim, quality of evidence, and analysis. A straw man or ad hominem misstep will cost credibility and clarity. Instead of attacking a writer’s character or oversimplifying their point, summarize opposing passages accurately and respond directly to them.

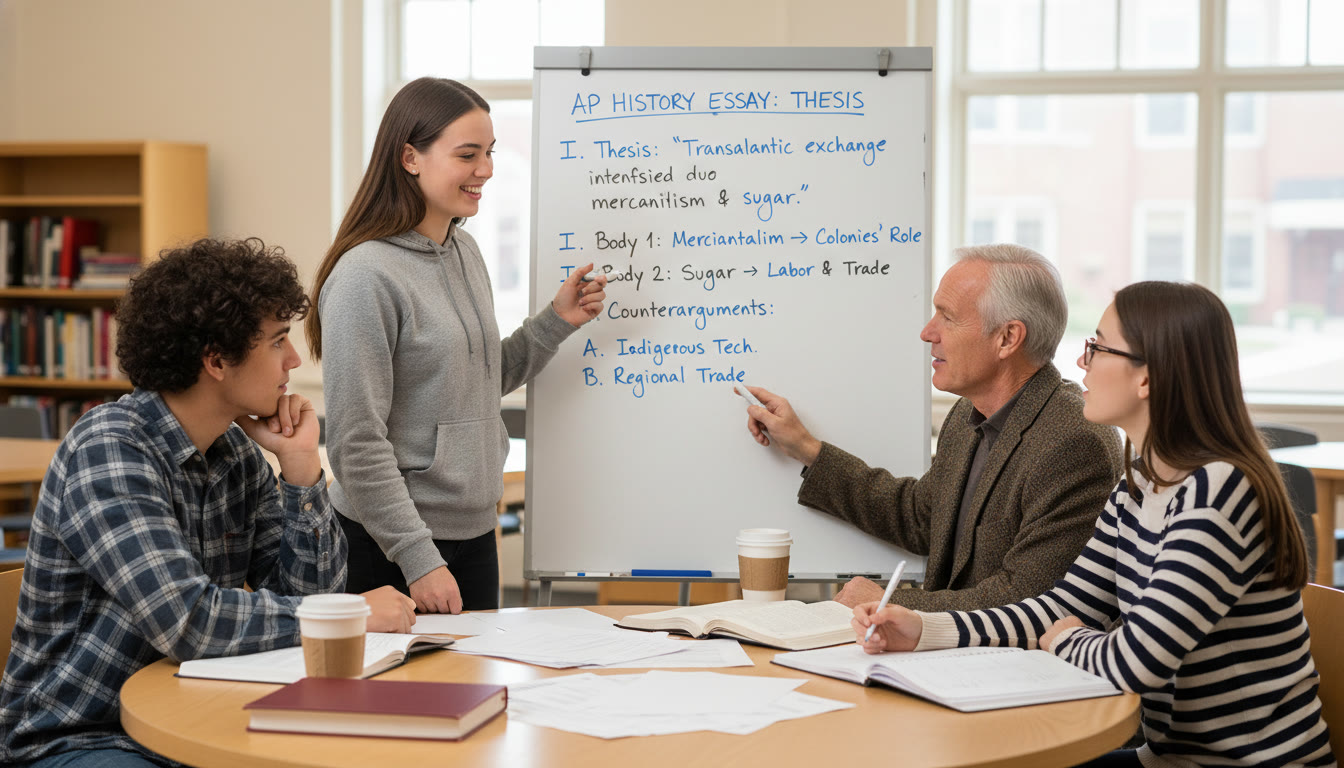

AP US History and AP Government

In historical and political essays, false cause and hasty generalization often crop up. Students may attribute complicated outcomes to single causes or extrapolate from one event to an entire era. The remedy: contextualize evidence, weigh multiple causes, and acknowledge contingency.

AP Biology, AP Psychology, and Other Sciences

Appeal to authority and correlation-causation errors are particularly dangerous in science writing. Cite studies carefully, discuss methods and limitations, and avoid claiming causation when only correlation is shown. If a study is correlational, say so — and explain what additional evidence would be needed to infer causality.

Practical Techniques to Avoid Fallacies (and Impress AP Readers)

Techniques matter more than memorizing names of fallacies. Use practices that sharpen reasoning and make your argument resilient.

- Write Backwards from Your Claim: Start with a precise thesis and outline the exact steps of reasoning from evidence to conclusion.

- Use Qualified Language: Swap absolute words (always, never) for measured ones (often, sometimes) when evidence isn’t universal.

- Play Devil’s Advocate: Briefly present the strongest counterargument and then refute it with evidence — this builds credibility.

- Demand Representative Evidence: Ask whether a study or example is typical, large enough, and methodologically sound before leaning on it.

- Check for Hidden Assumptions: Every argument rests on unstated premises. Make them explicit and test whether they hold.

- Annotate Sources: Note what type of evidence each source provides — primary, secondary, experimental, anecdotal — and use that to weight its influence.

Example: Turning a Weak Claim into a Strong One

Weak: “Schools that use tablets see test scores rise, so tablets improve learning.”

Stronger: “Some studies show test score increases in schools that adopted tablets; however, these results often coincide with concurrent investments in teacher training and curriculum redesign. To claim tablets alone improve learning, we need controlled studies that isolate the device’s effect.”

Using Evidence Correctly: A Short Checklist

Before you submit an AP essay, run through this quick checklist to catch common fallacies and strengthen your argument:

- Does each claim have evidence? If yes, is the evidence relevant and sufficient?

- Have you avoided attacking a person instead of their argument?

- Have you distinguished correlation from causation?

- Do you recognize alternative explanations?

- Have you considered counterarguments and addressed them fairly?

- Is your language appropriately qualified based on the strength of your evidence?

Table: Quick Repairs for Common Fallacies

| Problem | What You Wrote | Immediate Fix |

|---|---|---|

| Straw Man | “The author wants to ban X entirely.” | Quote the author’s precise stance; paraphrase neutrally; respond to that version. |

| Ad Hominem | “The politician is dishonest, so their plan is bad.” | Evaluate the plan’s merits and costs independently of the messenger. |

| Correlation / Causation | “When A happened, B followed, so A caused B.” | Look for controlled experiments, mechanisms, or alternative explanations. |

| Hasty Generalization | “I saw one X fail; therefore X always fails.” | Gather broader data or qualify the claim to a specific context. |

| Appeal to Authority | “Famous Prof. Z says so, so it’s true.” | Explain the authority’s expertise and use their work as one piece of evidence. |

Practice Exercises to Build Fallacy-Resistant Thinking

Learning to spot fallacies takes practice. Here are some short exercises you can do alone or with a study partner.

- Spot the Fallacy: Take five paragraphs from an editorial and identify any fallacies. Rewrite the paragraph without the flaw.

- Evidence Swap: Replace one piece of anecdotal evidence in a paragraph with empirical data and note how the argument shifts.

- Counterargument Drill: For your next practice essay, write the counterargument in full before your rebuttal — this forces clarity and fairness.

- Teach to Learn: Explain a common fallacy to a friend who doesn’t know it; answering their questions will expose gaps in your own understanding.

How Tutoring Can Accelerate This Practice

One-on-one guidance helps you spot subtle habits that cause repeated errors. For example, a tutor can review your typical essay structure, highlight recurring fallacies, and help design drills targeted to your weak spots. Personalized tutoring — like the tailored study plans and expert-guided practice offered by Sparkl — can accelerate progress by providing focused feedback and AI-driven insights that track improvement over time.

Applying These Lessons in Timed AP Settings

Timed exams add pressure that can make fallacies more likely. Here are tactical adjustments that work under time constraints:

- Quick Outline (3–5 minutes): Jot your thesis, main reasons, and one counterargument. Outlines prevent last-minute leaps to weak generalizations.

- Tag Your Evidence: In the margin, mark each piece of evidence as “strong/weak/needs context” so you don’t overuse weak anecdotes.

- Timebox Your Revision: Reserve the last 3–5 minutes to scan for obvious fallacies like hasty generalizations and ad hominem statements.

- Practice Under Real Conditions: Simulate exam timing and have a tutor or peer give feedback emphasizing logical rigor rather than only grammar.

Real-World Examples: Where Fallacies Sneak Into Everyday Arguments

Logical fallacies aren’t just exam problems — they show up in news articles, social media, and class debates. Being able to identify them helps you read more critically and argue more persuasively.

Example A: Social Media Claim

Post: “After City X started Program Y, crime dropped — so Program Y is why crime decreased.”

Why it’s risky: This ignores other factors like economic shifts, policing changes, or seasonal trends. A well-reasoned critique asks for multiple data points and looks for controlled studies or long-term trends.

Example B: In-Class Debate

Claim: “That idea is ridiculous — the person who suggested it failed last year.”

Problem: Ad hominem. Stronger debate responds to the idea’s merits and cites counter-evidence rather than leaning on past failures.

How to Turn Critique into Constructive Feedback

When you peer-review a classmate’s essay, your feedback should be honest but specific and useful. Here’s a short template you can use:

- Start with one strength: “Your thesis is clear and focused.”

- Point out one logical issue: “This paragraph assumes causation without proof. Consider adding study X or qualifying the claim.”

- Give a revision suggestion: “Replace the anecdote with a statistic, or reword to say ‘may be associated with’ rather than ’causes.'”

Putting It All Together: A Sample Essay Blueprint

Below is a compact blueprint you can follow to write fallacy-resistant AP essays.

- Intro (1 paragraph): Clear thesis, road map of main points, one relevant context sentence.

- Body Paragraphs (2–4 paragraphs): Topic sentence, evidence, explanation of how evidence supports claim, quick note on limitations or alternative interpretations.

- Counterargument Paragraph (1 paragraph): Present the strongest opposing point, then respond with evidence and reasoning.

- Conclusion (1 paragraph): Synthesize, restate thesis in light of evidence, suggest implications or further questions.

A Word on Tone: Persuasion Without the Posturing

Logical clarity and emotional intelligence go hand-in-hand. An effective AP writer is confident but humble — willing to qualify claims and acknowledge complexity. Avoid sweeping declarations and rhetorical tricks that mask weak evidence. Readers (including AP readers) appreciate honesty: a well-reasoned, cautious claim often scores better than a flashy but flimsy one.

How to Integrate Tutoring and Tools into Your Practice

Tutoring can transform vague advice into tangible improvement. If you’re studying independently, use targeted help to:

- Identify the fallacies you most often commit through essay reviews.

- Create a personalized study plan that builds logical skills alongside content knowledge.

- Use one-on-one sessions for focused drills — for example, rewriting straw man statements into fair summaries.

- Leverage AI-driven insights to track recurring errors and measure progress over time.

Services that combine human tutors with data-driven feedback — such as Sparkl’s personalized tutoring approach that offers 1-on-1 guidance, tailored study plans, expert tutors, and AI-driven insights — can help you practice more efficiently and make the most of limited study time.

Final Checklist Before You Hand In That Essay

Run through this final checklist to make sure your argument is tight, fair, and persuasive:

- Is my thesis clear and defensible?

- Have I used relevant and sufficiently strong evidence?

- Did I avoid attacking people instead of arguments?

- Have I distinguished between correlation and causation?

- Did I present and fairly address a counterargument?

- Is my language appropriately cautious where the evidence is limited?

- Have I given the reader a clear line from evidence to conclusion?

Parting Thought: Logic Is a Habit, Not a Trick

Becoming fallacy-proof isn’t about memorizing labels — it’s about developing habits of careful thinking, generous reading, and disciplined writing. Start small: one revision habit, one outlining trick, one guided tutoring session. Over time, these steps compound into clarity and confidence. When your ideas are structurally sound, your passion has the power to persuade.

If you want targeted practice, consider pairing your study plan with personalized tutoring that zeroes in on the logic mistakes you make most often. The difference between a good essay and a great one is often a few minutes of focused revision guided by someone who sees your patterns. Practice deliberately, argue honestly, and let evidence lead the way.

No Comments

Leave a comment Cancel