Why the MCQ Blueprint Matters

Multiple-choice questions (MCQs) on AP exams are not random puzzles — they are carefully engineered assessment tools. The College Board crafts MCQs to discriminate between levels of understanding, to reveal common misconceptions, and to test application as much as recall. If you approach them like a chaotic grab-bag of options, you’ll waste time and energy. If you learn the blueprint — how distractors are built and how to flag wisely — the section becomes a series of solvable patterns rather than a guessing gauntlet.

What Is a Distractor — and Why It’s Not Just a Wrong Answer

In testing language, a wrong option on an MCQ is called a “distractor.” Good distractors are persuasive — they often reflect common student errors, misapplied formulas, misread phrasing, or plausible but incomplete reasoning. Great distractors tell the test author what misconceptions are widespread; for you, they tell a story about what the test-makers expect to trap.

Types of Distractors You’ll Meet on AP Exams

- Close-but-Not-Complete: These answers hit part of the logic but omit a critical nuance.

- Miscalculation or Unit Error: Common in sciences and statistics — correct method, wrong arithmetic or wrong unit conversion.

- Surface-Reading: Options that match a phrase in the passage or question stem but ignore deeper context.

- Opposite-Polarity: The logically opposite claim — useful when students overgeneralize.

- Trap from Misapplied Rules: Answers that rely on a rule applied out of context (e.g., a grammar rule used where a usage exception applies).

- Random Guess-Level: Implausible options that are there to catch guessers — less common on high-quality AP items.

How to Read Distractor Patterns — A Step-by-Step Strategy

Think of each MCQ as a mini-mystery. The clue is the stem and any accompanying material; the suspects are the answer choices; the pattern of distractors tells you how the test-maker expects students to think. Here’s a reproducible approach.

1. Pre-Read the Question Stem and Constraints

Before looking at options, read the stem carefully and identify exactly what is being asked — not broadly, but precisely. Is it asking for the best interpretation, the most likely consequence, a numerical value, or the single best definition? Mark keywords: “most likely,” “except,” “not,” and any units or qualifiers. Knowing the constraint prevents lure-in by distractors that satisfy only part of the stem.

2. Predict an Answer (Even Roughly)

Make a quick mental or written prediction. It can be as simple as “positive relationship” or “use conservation of energy.” With that prediction in mind, scanning options becomes a filtering task, not an aimless hunt.

3. Classify Each Option Against Your Prediction

Ask: Does this match my prediction exactly, partially, or not at all? Label options mentally as: Match, Partial, or Mismatch. Often, one Match appears and a couple Partial answers trap students who stop too early.

4. Use the Distractor-Story Test

For every option you consider, briefly ask how a student would plausibly arrive at that answer. If an answer’s pathway is a one-step misread, it’s a classic surface-reading distractor. If it requires a small arithmetic slip, it’s a miscalculation distractor. This analysis helps you reject options that are attractive only when the reader makes a predictable mistake.

Flagging Smart: When to Mark and When to Move On

Flagging is a time-management and metacognition tool. Done right, it gives you a second-pass strategy that prioritizes energy for the questions with the highest payoff. Done poorly, it becomes a procrastination device.

Two Principles of Effective Flagging

- Mark if you have partial traction: If you can eliminate at least one or two options but aren’t sure about the final choice, flag it. Partial elimination means the question is winnable with a revisit.

- Skip quickly if it’s a dead sprint: If the stem uses unfamiliar material and you have no anchor to make even one elimination on a timed pass, skip and come back. Time is the scarce resource.

How to Prioritize Flagged Items

- First pass: answer what you confidently know.

- Second pass: tackle flagged questions where you eliminated at least one choice — these are high-probability wins.

- Last pass: any remaining flagged questions with no elimination — here apply educated guessing (more on smart guessing below).

Smart Guessing: When You Must Pick and How to Improve Odds

The College Board does not penalize for wrong answers on AP multiple-choice sections, so guessing when you can reduce options is mathematically sensible. But guess intelligently:

- Always eliminate any obviously wrong choices first. Each eliminated option increases your odds.

- Avoid random guesses when you have zero eliminations — that’s where a quick re-check of the stem often pays.

- Watch for answer patterns that are statistically rare: for example, if three choices are numerical and one is qualitative, sometimes the qualitative is correct (and vice versa), depending on the subject. This is a heuristic, not a rule.

Examples: Reading Distractors in Different AP Subjects

Distractor design varies across subjects because the common errors students make vary. Below are examples that show the same underlying blueprint applied differently.

AP Biology — Misapplied Process

Stem: “Which cellular process directly provides the energy to power active transport across the membrane?”

A student who confuses photosynthesis with ATP production might pick an answer related to light-dependent reactions; the distractor is crafted to trap surface connections. Better answers will require you to differentiate between processes that create ATP versus processes that use ATP.

AP Chemistry — Unit and Stoichiometry Traps

Common distractors include answers that come from correct stoichiometric setup but incorrect mole-to-mass conversion, or answers that swapped liters and moles. Here, writing the unit at each step helps you catch those traps.

AP English Language — Tone vs. Content

Options may reflect tone, rhetorical strategy, or literal content. Distractors often repeat words from the passage to lure a surface reader. The robust strategy: paraphrase the author’s claim before reading options, then match tone choices against your paraphrase.

Using Time and Section Structure to Your Advantage

AP exams usually set a fixed number of questions for a defined time window; pacing is central. Divide the section into time blocks and set micro-goals. For example, if you have 60 questions in 60 minutes, aim for 45–48 in the first 45 minutes with confident answers, leaving 12–15 minutes for flagged and tougher questions. That buffer is where your flagged strategy shines.

Data Table: A Simple Pacing and Flagging Plan You Can Use

| Section Length | Target Questions in First Pass | Expected Flags | Second Pass Time | Final Review |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 60 minutes / 60 questions | 45–48 | 10–15 | 12–15 minutes | 2–3 minutes for last-ditch educated guesses |

| 40 minutes / 40 questions | 30–32 | 6–10 | 6–8 minutes | 2–4 minutes |

Practical Exercises to Internalize Distractor Patterns

Theory is useful, but pattern recognition builds with practice. Here are drills you can add to your study plan.

Drill 1: Elimination Sprints

- Take a set of 10 practice MCQs from AP Classroom or a released exam.

- For each question, spend 45 seconds predicting the answer without looking at choices.

- Then, read options and mark which you can eliminate and why. Record the type of distractor that fooled you (surface-reading, calculation, misapplied rule, etc.).

Drill 2: Distractor Autopsy

- After completing a practice set, analyze every question you missed. For each wrong option you chose, write the short path that led you there.

- Repeat this for a week; you’ll find recurring personal mistakes to target.

Drill 3: Timed Flagging Simulation

- Simulate exam timing and force yourself to flag under the rules you set (e.g., only flag if you can eliminate one choice).

- Track percentage of flagged questions you later answer correctly — this tells you whether your flagging threshold is too loose or too strict.

The Role of AP Classroom and Official Resources

College Board’s AP Classroom and released practice questions are invaluable because they reflect real distractor design. Use them not just to test content knowledge but as data: which types of distractors recur in your subject? Which common missteps appear for many students? That insight lets you adjust study habits toward conceptual clarity rather than memorization.

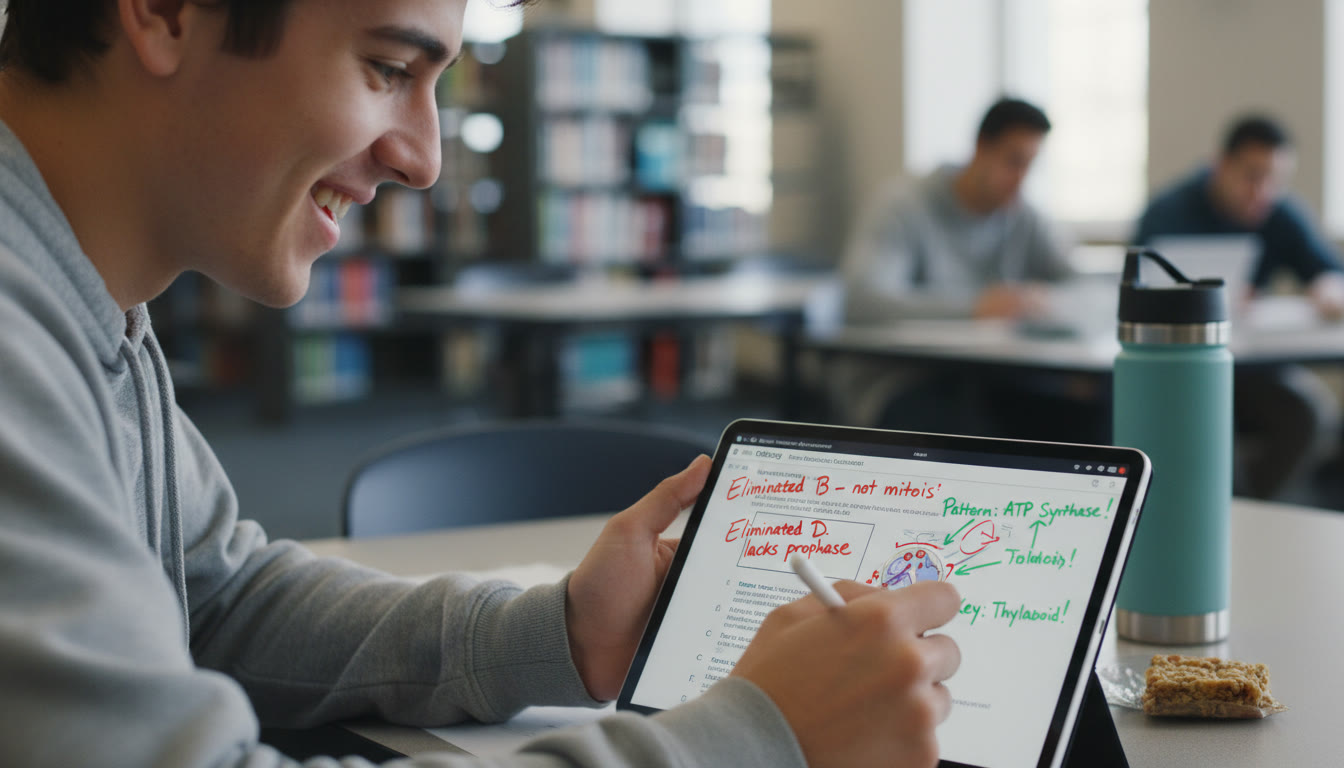

How Personalized Tutoring Multiplies Pattern Recognition

Recognizing distractor patterns is partly an individual skill: it depends on your prior misconceptions and study habits. That’s where personalized tutoring — like Sparkl’s 1-on-1 guidance — can accelerate progress. A skilled tutor can:

- Diagnose your recurring distractor pitfalls (e.g., algebra slips, reading-for-keywords, conceptual gaps).

- Create a tailored study plan that targets those patterns with specific drills.

- Offer expert, subject-specific strategies and immediate feedback that you won’t get from self-study alone.

When tutoring is combined with data-driven insights (for example, tracking which distractors you select most often), your practice becomes surgical instead of scattershot, and the gains compound quickly.

Common Student Mistakes and How to Fix Them

Below are real behaviors students report — and simple, practiceable fixes.

Mistake: Reading Too Fast

Fix: Slow down on the stem. Underline qualifiers. Paraphrase the question before scanning answers.

Mistake: Stopping After One Elimination

Fix: Force yourself to eliminate at least two choices before settling on an answer. If you can only eliminate one, flag it for second-pass.

Mistake: Overreliance on Keyword Matching

Fix: Ask whether the answer matches the broader idea, not just a phrase. Test-makers often include wording from the passage to lure readers who skim.

Mistake: Weak Number Sense / Units

Fix: Practice quick unit checks and back-of-envelope order-of-magnitude estimates. Often you can eliminate answers by seeing that the number is wildly off.

Course-Level Differences: Tailoring the Blueprint

Not all AP subjects produce the same distractor ecosystem. Here’s how to adapt:

- STEM (Biology, Chemistry, Physics, Calculus): Expect calculation and concept-application traps. Show your work enough to spot unit errors and sign mistakes.

- Humanities (English, History): Expect surface-reading and nuance traps. Practice paraphrase and tone-distinction drills.

- Social Sciences (Psychology, Economics): Expect distractors based on common theoretical misinterpretations or misapplied models.

When to Use Technology — and When to Step Away

Digital practice platforms and AI tools can analyze your answer patterns and surface the distractors that fool you most. That is powerful, but beware passive reliance: analytics are only as useful as the actions you take. Pair any technology with deliberate practice and reflection. For example, a Sparkl tutor can help interpret analytics and convert them into a focused drill plan.

Putting It All Together: A 6-Week MCQ Mastery Plan

Below is a compact, structured routine to transform your MCQ performance. Adapt the timeline to fit your exam date.

- Week 1: Baseline. Timed practice set from an official source. Identify top three distractor types that trap you.

- Week 2: Targeted drills. Do daily elimination sprints focused on those distractor types.

- Week 3: Tutoring diagnostics. Book 1–2 sessions for focused feedback; refine your flagging threshold and pacing.

- Week 4: Mixed practice. Simulate full sections with strict flagging rules and time blocks from the table above.

- Week 5: Autopsy and repair. For every missed question, run the distractor autopsy and rewrite the stem in your own words.

- Week 6: Final polishing. Reduce stress by practicing test-like conditions and review your personal error bank.

Measuring Progress: Metrics That Matter

To track improvement, use metrics that reflect both accuracy and test-smart behavior:

- Raw accuracy on timed sets (percentage correct).

- Flagged-question conversion rate (what percent of flagged items you answer correctly on second pass).

- Average time per question on confident answers vs. flagged ones.

- Distribution of distractor types selected — this points to persistent conceptual errors.

Final Notes — Mindset, Not Magic

Developing MCQ mastery is not about finding a single trick but about building habits: careful reading, prediction, elimination, and reflective review. Distractor patterns are predictable because human learners fall into predictable errors. Train your brain to spot those errors in practice so that on test day they become visible in seconds.

Remember: improving at MCQs is a multiplier. Better MCQ skills save time and cognitive energy that you can then spend on free-response sections where depth matters. If you want to compress this learning curve, combine disciplined practice with targeted feedback. Sparkl’s personalized tutoring — with 1-on-1 guidance, tailored study plans, expert tutors, and actionable insights — can be an efficient way to focus your effort and convert practice into reliable exam performance.

Quick Reference Checklist: Before You Start an MCQ Section

- Scan time and questions; set micro-goals.

- Read each stem carefully; underline qualifiers.

- Predict an answer before seeing options.

- Eliminate obviously wrong choices; flag when only one elimination is possible.

- Prioritize second-pass flagged items where you had at least one elimination.

- Use educated guessing on remaining or time-pressed items.

Closing Encouragement

Mastering AP MCQs is an eminently learnable skill. The blueprint is not a secret — it’s a set of patterns you can practice and internalize. Treat each practice question as both an exam item and a data point about how your thinking works. Over time, you’ll stop being surprised by distractors and start using them to your advantage. Study with intention, keep a growth mindset, and get help when you need it — that combination is where scores move.

Good luck — and remember, the best test-day confidence comes from doing the intentional, slightly uncomfortable work in practice that makes the exam itself feel manageable and fair.

No Comments

Leave a comment Cancel