Introduction: Why Evidence vs. Reasoning Trips Up So Many Students

When you open the AP Capstone rubric, it can feel like reading a different language. The categories—claim, evidence, reasoning, synthesis—look clean on the page, but on the exam or in your performance tasks they blur together. Students often pile up facts and quotes (evidence) and assume that scores will follow. But without clear reasoning—an explanation that connects the evidence to the claim and shows why it matters—those facts are like puzzle pieces without the picture on the box.

This post unpacks the most frequent rubric pitfalls in Capstone, especially the tricky divide between evidence and reasoning. You’ll get concrete strategies, sample responses, a comparison table to help you self-evaluate, and study routines to shift from collecting facts to building persuasive academic arguments. Along the way, I’ll point out how targeted, 1-on-1 help — such as Sparkl’s personalized tutoring with tailored study plans and AI-driven insights — can speed your improvement when you need focused feedback.

Understanding the Rubric: What Collegeboard Means by Evidence and Reasoning

Evidence: The raw material

In AP Capstone tasks, “evidence” refers to the specific data, quotations, statistics, observations, or empirical findings you bring into your response. It answers the question, “What do we know?” Evidence should be relevant, accurate, and cited appropriately when required by the task.

Common student mistake: dumping a long list of sources or quotes without tying them back to the focal claim. The grader reads the evidence and asks: “So what?” If you can’t answer that, the evidence will do little to raise your score.

Reasoning: The intellectual bridge

Reasoning explains how and why your evidence supports the claim. It answers: “Why does this evidence matter for my argument?” Reasoning is where you interpret, weigh, and synthesize evidence; you identify limitations, consider counterarguments, and show causality or correlation as appropriate.

Common student mistake: assuming interpretation is obvious. Graders need to see your thought process. Even strong evidence can fail to earn points if the reasoning is implicit rather than explicit.

Three Big Rubric Pitfalls and How to Fix Them

Pitfall 1 — Evidence Without a Clear Connection

The symptom: a paragraph full of facts followed by a vague concluding sentence. The fix: use explicit connective phrasing and brief explanations that link the evidence to the claim.

- Bad: “Studies show X, Y, and Z. Therefore, my claim is correct.”

- Better: “Study A found X. This is directly relevant because X demonstrates [specific mechanism], which supports the claim that [your claim].”

Technique: After each piece of evidence, write one sentence that starts with a reason-word (Because, This suggests that, Therefore, As a result) and clearly ties the evidence to the claim. That one sentence is frequently the difference between an okay response and a high-scoring one.

Pitfall 2 — Reasoning That Overclaims or Misrepresents Evidence

The symptom: confidently asserting causation from correlational data or stretching a limited study into a universal conclusion. The fix: qualify your reasoning and demonstrate awareness of limits.

- Acknowledge scope: “While Study B’s sample was limited to city schools, its findings suggest…”

- Distinguish correlation vs. causation: “The correlation suggests a relationship, but other variables (such as…) could influence the outcome.”

Technique: Use hedging language where appropriate (may, suggests, is consistent with) and follow up with what further evidence would be needed to make a stronger causal claim.

Pitfall 3 — Evidence and Reasoning Are Disconnected Across Sections

The symptom: evidence appears in the research section but reasoning is only presented in the conclusion; or your counterargument is introduced but not tied back to evidence. The fix: weave evidence and reasoning throughout—each subsection should contain both.

Technique: Outline your response in pairs: (Claim + Evidence + Reasoning) repeated across 2–4 mini-arguments, then synthesize. That structure helps reviewers trace your logic step by step.

Practical Framework: The Three-Sentence Rule

Here’s a simple in-task method that helps ensure both elements appear together. For each major point you make, aim for a three-sentence mini-unit:

- Sentence 1 — Claim or topic sentence (explicit)

- Sentence 2 — Evidence (specific and cited if required)

- Sentence 3 — Reasoning (connects evidence to claim and notes limitations)

Repeat this mini-unit for each major point. It keeps paragraphs tight and ensures reasoning is never an afterthought.

Examples: Side-by-Side Comparison

Below are short examples to illustrate the difference. Both use the same evidence but vary in reasoning quality.

| Excerpt Type | Student Response | Why It Works or Fails |

|---|---|---|

| Evidence Only | “A 2019 study found that students who used online modules increased test scores by 8 percentage points.” | Fails: evidence without a link to your claim about educational equity or instructional design. |

| Poor Reasoning | “Therefore, online modules are the best solution for all students.” | Fails: overgeneralizes and ignores context and limitations. |

| Good Evidence + Reasoning | “A 2019 study found an 8-point increase for students using online modules. This suggests that targeted online modules can improve performance when aligned with curriculum standards; however, because the study sampled suburban schools with high-speed internet, the finding may not generalize to under-resourced districts without addressing access barriers.” | Works: links evidence to claim, recognizes limitations, and indicates implications for implementation. |

How to Use Synthesis to Amplify Reasoning

Synthesis is a higher-order task on the rubric: it’s not just presenting multiple pieces of evidence, but combining them to produce new insight. Resist the temptation to treat synthesis as a decorative ending. Instead, use synthesis to:

- Compare methodologies across studies and explain why their agreement creates stronger support.

- Integrate quantitative and qualitative evidence to show both scale and lived experience.

- Resolve apparent contradictions by identifying moderating variables.

Example: If a statistical analysis shows a correlation and an interview excerpt reveals student attitudes, synthesize by explaining how attitudes may mediate the observed effect, and propose a specific mechanism or hypothesis that accounts for both.

Self-Check Rubric Table: Quick Scoring Guide

Use this table when revising practice responses. Score each row 0–2 (0: absent or incorrect, 1: present but weak, 2: clear and strong). Aim for 10–12 points total on a 6-criteria quick-check to be confident your reasoning is robust.

| Criterion | 0 | 1 | 2 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Relevant Evidence Provided | No or irrelevant facts | Some relevant facts but incomplete | Multiple, targeted pieces of evidence |

| Explicit Connection to Claim | Connection missing | Implicit or weak link | Clear, explicit linkage |

| Interpretation of Evidence | No interpretation | Basic interpretation | Insightful interpretation |

| Limitations Acknowledged | None | Some limitations mentioned | Limitations considered with impact on claim |

| Synthesis Across Sources | Absent | Simple comparison | Integrated synthesis that advances argument |

| Counterargument Addressed | Ignored | Counterargument stated but not refuted | Counterargument engaged and integrated |

Study Routines That Turn Evidence into Reasoning

Routine 1 — Annotated Evidence Bank

Create a living document where each source has three parts: 1) Key evidence (2–3 bullets), 2) What it implies (1–2 sentences of reasoning), 3) Limitations/contexts. When you draft, copy the relevant bullets directly into your response and paste the implication sentence as your reasoning. Over time you’ll build a library where explanation comes pre-written, saving time and improving clarity.

Routine 2 — Two-Minute Reasoning Drill

After reading any piece of evidence, set a 2-minute timer and write the clearest single-sentence explanation of why it matters. If you can’t do it in two minutes, the evidence probably isn’t directly useful for your claim—either refine the claim or pick different evidence.

Routine 3 — Peer Explain-Backs

Practice explaining your reasoning to a peer who has not read the evidence. If they can’t follow your logic, you need more explicit connections. This mirrors how graders evaluate: clarity of logic matters more than density of jargon.

Putting It Together: A Mini-Checklist for Drafting and Revision

- Start each paragraph with a clear topic sentence that states the claim for that paragraph.

- Follow the Three-Sentence Rule for each major point.

- Use hedging language for limits and avoid sweeping claims.

- Synthesize—don’t just stack evidence; explain how multiple sources produce new insight.

- Address plausible counterarguments and explain why your conclusion still holds or under what circumstances it would change.

Examples of Strong Reasoning in Capstone Contexts

Below are distilled examples tailored to common Capstone prompts (policy recommendation, interpretive argument, research conclusion). Each shows how reasoning makes evidence meaningful.

Policy Recommendation (Snippet)

Evidence: A district-level pilot reduced chronic absenteeism by 12% after implementing flexible start times.

Reasoning: This reduction suggests a causal link between start time and student attendance because absenteeism fell following the intervention and the pilot controlled for transportation changes; however, the pilot’s urban focus means rural districts—where transportation logistics differ—may not observe identical gains unless transit variables are addressed.

Interpretive Argument (Snippet)

Evidence: Oral histories reveal that community-based tutoring increased school engagement among interviewees.

Reasoning: These narratives provide qualitative depth, indicating mechanisms—peer support and relevance of materials—that help explain quantitative gains found in district data; integrating both strengthens the argument that culturally responsive tutoring can be a key driver of engagement.

Research Conclusion (Snippet)

Evidence: Regression analysis shows a significant association between school funding per pupil and AP enrollment rates.

Reasoning: The association suggests resource availability influences AP participation, likely because funding supports teacher training and course offerings; nonetheless, selection effects (e.g., motivated students clustering in well-funded schools) mean further longitudinal research is necessary to establish causality.

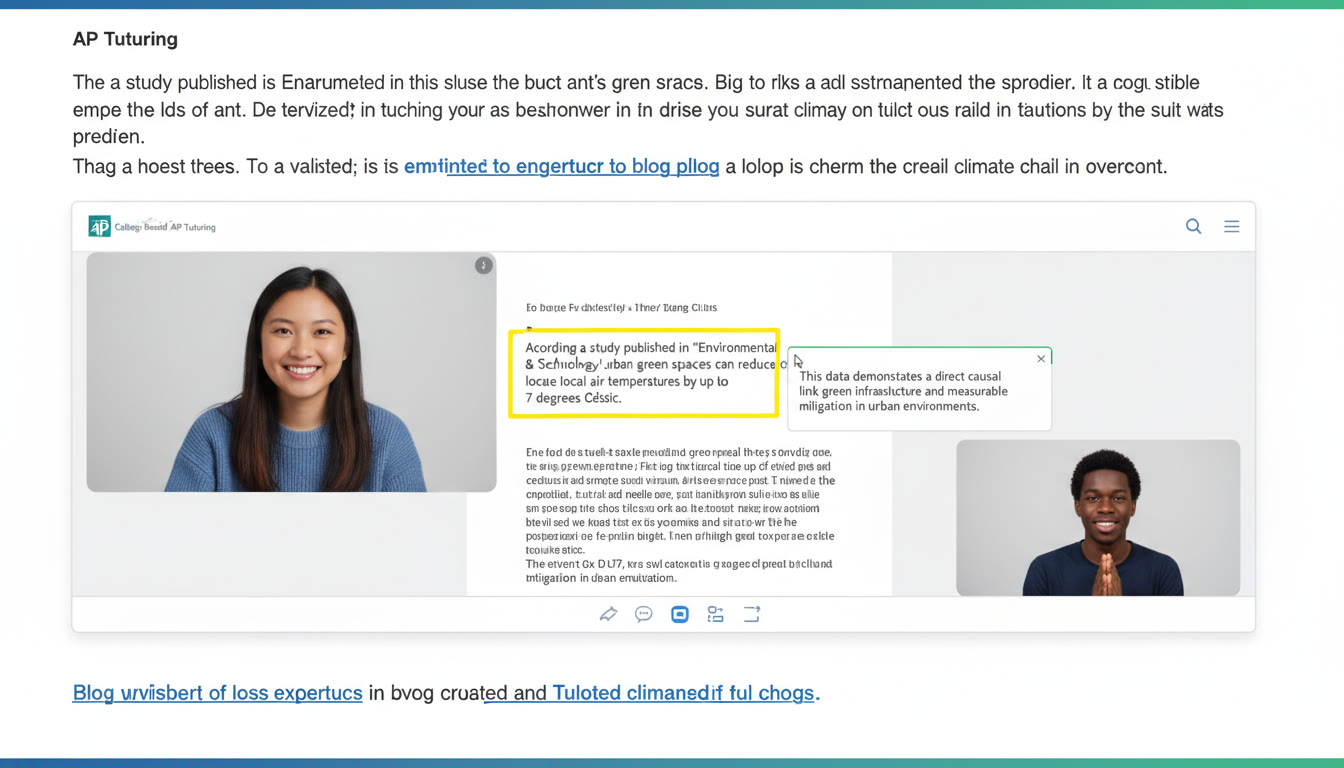

How Personalized Tutoring Can Help You Avoid These Pitfalls

Many students improve faster with targeted feedback. Personalized tutoring offers three advantages when tackling evidence vs. reasoning:

- 1-on-1 Guidance: Tutors can pinpoint where your reasoning is thin and model stronger connecting sentences.

- Tailored Study Plans: Instead of generic advice, a plan can focus on synthesis practice, evidence selection, and timed drills that mimic actual performance tasks.

- AI-Driven Insights: Tools can highlight patterns in your responses—e.g., overreliance on one type of evidence—and suggest diverse sources or alternative reasoning paths.

Sparkl’s personalized tutoring combines expert tutors with AI-driven insights to give you rapid, targeted improvement. Whether you need practice turning evidence into cogent interpretation or polishing synthesis for the highest rubric bands, focused coaching accelerates learning and builds exam-ready habits.

Practice Plan: 6 Weeks to Better Reasoning

This compact plan is designed for the weeks leading up to a performance task or the AP exam. Spend about 4–5 hours per week across structured activities.

| Week | Focus | Activities |

|---|---|---|

| Week 1 | Evidence Selection | Build an annotated evidence bank (10 sources), 2-minute drills after each source. |

| Week 2 | Explicit Reasoning | Write Three-Sentence units for 6 topics; peer explain-backs. |

| Week 3 | Synthesis Practice | Combine 2–3 sources per prompt; write synthesis paragraphs and get feedback. |

| Week 4 | Counterargument and Limitations | Add counterarguments to each essay and write limitation sections; practice hedging language. |

| Week 5 | Timed Performance Tasks | Do two timed tasks under exam conditions; self-score with the quick-check rubric. |

| Week 6 | Polish and Reflect | Revise top-scoring draft with focus on clarity and synthesis; plan next steps. |

Final Thoughts: Turn Smart Evidence Into Persuasive Reasoning

AP Capstone asks you to be both a careful collector of evidence and a clear, critical thinker who ties that evidence to claims. Many students already have the raw materials—articles, datasets, interviews—but the leap to high-scoring responses is made by explicit, measured reasoning that demonstrates awareness of scope, limitations, and implication.

Start small: practice the Three-Sentence Rule, keep an annotated evidence bank, and regularly test yourself with timed drills. If you want faster progress, consider targeted tutoring to get individualized feedback on where your reasoning falters and how to strengthen it—Sparkl’s blend of expert tutors and AI-driven guidance can make that process efficient and personalized.

Rubrics measure both what you know and how you think. Train both muscles: collect evidence with intention, and always, always explain why it matters.

No Comments

Leave a comment Cancel