Why “Evidence of Iteration” Matters — and Why Reviewers Notice It

If you’re building an AP Art portfolio or an AP Capstone project, you’ve likely heard the phrase “evidence of iteration” a dozen times. But what does it really mean? In simplest terms, evidence of iteration shows how your ideas evolved — not just the finished product. It reveals your thinking, your experiments, your failures and discoveries, and how each step moved you closer to a stronger outcome.

Reviewers aren’t only grading the final work. They’re evaluating your creative and intellectual journey. For AP Art and AP Capstone, showing iteration communicates critical habits: curiosity, resilience, reflective practice, and the ability to refine based on feedback or new information. When done well, iteration turns a portfolio from a set of isolated pieces into a compelling story about growth.

What Reviewers Look For

- Clear development: early attempts, mid-course corrections, and the finished piece.

- Intentional decisions: why you chose to change a composition, method, or argument.

- Evidence of testing: thumbnails, prototypes, drafts, experiments, or pilot studies.

- Reflective notes: captions, artist statements, research annotations, or feedback logs.

- Range of approaches: different techniques, materials, perspectives, or methodologies explored.

Start with a Plan: Make Iteration Part of Your Workflow

Iteration isn’t just a checkbox to tick at the end — it’s a workflow. When you build iteration into your process, the documentation becomes effortless and authentic. Here’s a simple workflow you can adopt:

- Discover: Research, inspiration collection, and idea generation.

- Prototype: Quick sketches, thumbnails, mockups, or mini-experiments.

- Test: Try a technique, gather feedback, or run a pilot.

- Reflect: Make notes about what worked, what didn’t, and why.

- Refine: Apply changes and produce the next version.

- Document: Save dated files, take photos, and write short captions about each step.

When this is habitual, you’ll naturally accumulate convincing artifacts of iteration — and you’ll be able to choose the best ones to display in your AP submission.

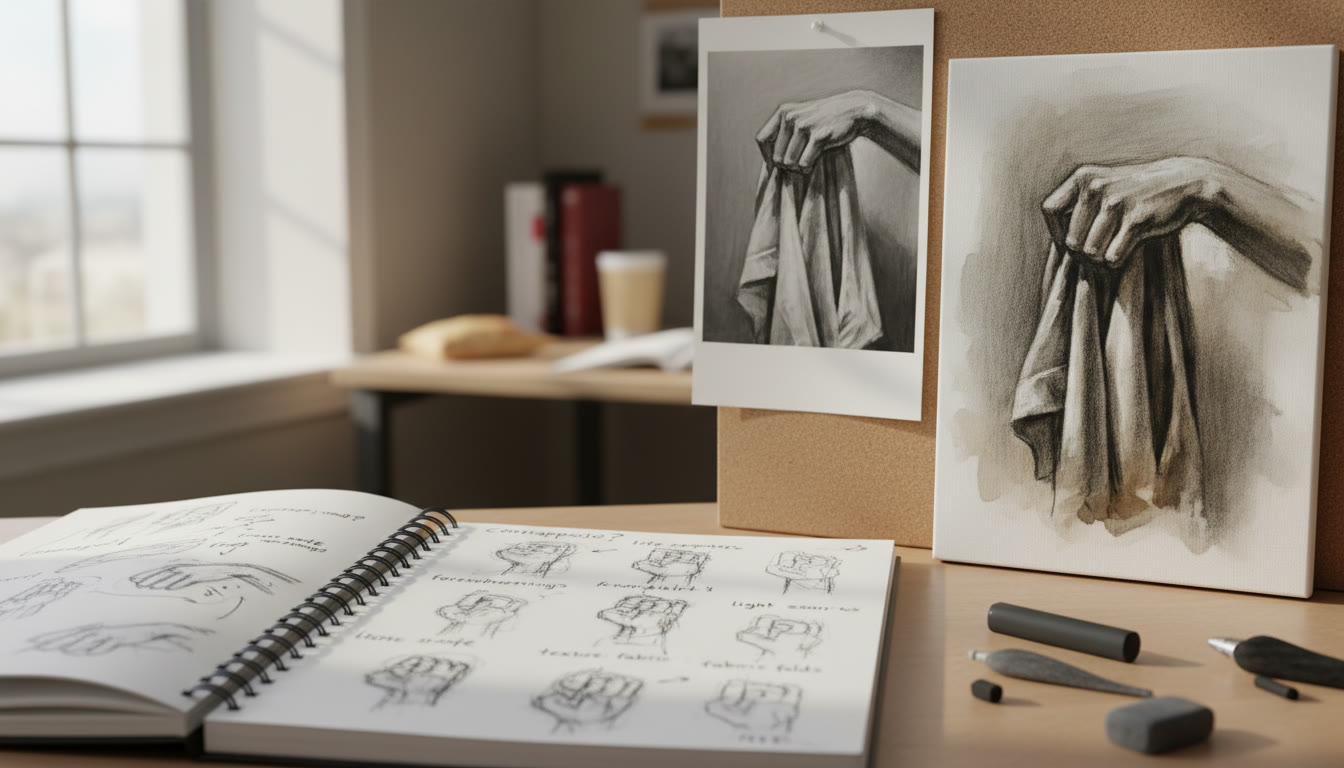

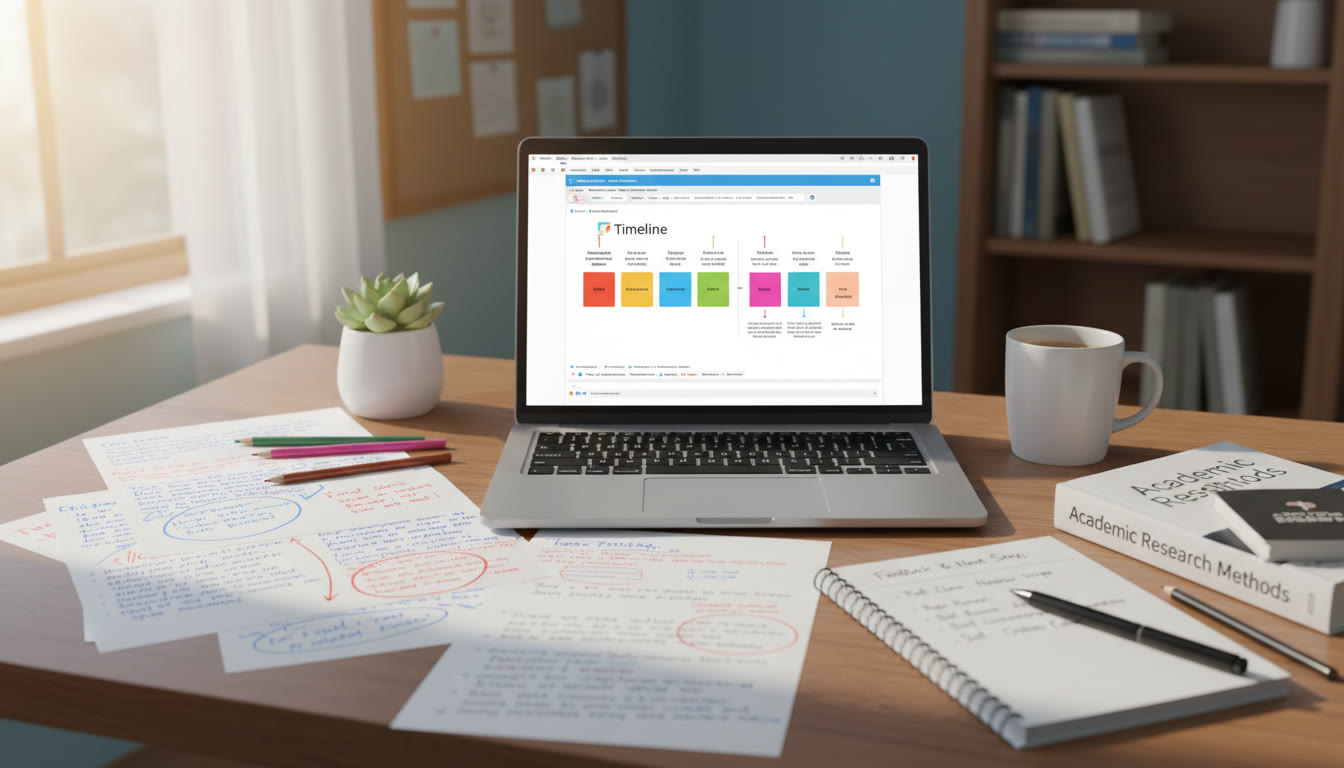

Concrete Examples: Iteration in Visual Art vs. Capstone Research

Evidence of iteration looks different depending on whether you’re in a studio-based course (AP Art and Design) or a research-focused course (AP Capstone: Seminar or Research). Here are side-by-side examples so you can visualize what to collect.

| Aspect | AP Art & Design (Studio) | AP Capstone (Research) |

|---|---|---|

| Early Stage | Thumbnails, mood boards, material tests. | Initial research questions, annotated bibliography, exploratory surveys. |

| Prototype | Small-scale maquettes, color studies, texture swatches. | Pilot study, preliminary data collection, sample interviews. |

| Feedback | Peer critique notes, teacher comments, photos showing issues. | Peer review, advisor feedback, statistical checks. |

| Revision | Reworked composition, adjusted palette, technical refinements. | Refined hypothesis, improved methodology, re-sampled data. |

| Final | High-quality documentation of the finished piece with comparative images. | Final report, appendices with raw data and iteration log. |

How to Capture Strong Pieces of Evidence

Not every sketch or draft needs to be included. Quality matters more than quantity. Here’s how to choose compelling evidence that tells a clear story.

1. Capture the Turning Points

Choose artifacts that show a meaningful change — a moment where new information or a bold choice shifted the project. A turning point might be a thumbnail that led to a new composition, a failed glaze test that changed your material approach, or a pilot survey whose results changed your research question.

2. Use Before/After Comparisons

Side-by-side images are intuitive and persuasive. For studio work, show a cropped photo of an early attempt next to a detailed shot of the final area where you applied that learning. For research, show a table or figure from the preliminary analysis alongside a revised version that addresses earlier limitations.

3. Include Short Reflections

Write 1–3 sentences that explain the decision behind each change. These captions are crucial. They help reviewers understand your reasoning without sifting through dozens of unlabeled images or files. For example:

- “Switched from acrylic to oil because overlapping glazes created the depth I needed; color study shows the result.”

- “Pilot interviews revealed a bias in my question wording, so I rephrased to elicit more open responses.”

4. Show Breadth and Depth

Balance demonstrating range (different approaches you tried) with depth (a clear line of development toward your final solution). For instance, you might show three distinct concept directions, then three iterations within the chosen direction that lead to the final piece.

What to Photograph and How to Label It

Presentation matters. Photographs should be well-lit and cropped thoughtfully; labels should be concise and informative. Here’s a quick checklist for photographing and labeling your process items.

- Use consistent lighting and neutral backgrounds for artwork photos.

- Take detail shots and full-view shots when relevant.

- Date each photo and keep filenames consistent (e.g., 2025-03-12_thumbnails_01.jpg).

- Include a short caption: Date, Step (Draft/Prototype/Revision), and 1-2 sentence reflection.

Sample Label Format

2025-03-12 | Prototype Sketch #3 | Decided to flip the focal point to the left to balance negative space after teacher critique.

Using Documentation Tools: From Analog to Digital

You don’t need fancy software to document iteration — a phone camera and a Google Drive folder will do. That said, organizing your materials will pay off when you assemble your final submission.

- Analog-first: Keep a sketchbook or physical folder where every page is dated and annotated.

- Digital-first: Use cloud folders with subfolders named by date and stage (e.g., “2025-04-Portfolio/Prototypes”).

- Hybrid: Photograph sketchbook pages, upload them immediately, and transcribe short reflections so everything is searchable.

What Counts as Iteration — Don’t Overthink It

Sometimes students worry whether a small change is meaningful enough. The rule of thumb: if a change affected your decisions or improved the work in some observable way, it’s worth documenting. Common valid forms of iteration include:

- Material or technique tests.

- Changes in scale or crop.

- Color palette experiments.

- Shifts in conceptual focus or research question.

- Responses to feedback and how you solved problems revealed by critique.

Examples of Meaningful Iteration

Example 1 (Studio): You test three ways of rendering a hand (gestural line, tonal block-in, and mixed-media collage). The tonal block-in communicated light most effectively, so you refined that approach and documented the tonal studies and the subsequent changes in the final piece.

Example 2 (Research): An initial survey yields low response rates. You redesigned the survey, shortened it, and changed distribution channels. The comparison of response rates and the resulting change in sample demographics becomes evidence of iteration.

Organize Your Submission: A Practical Template

When it’s time to assemble your AP submission, structure your documentation so reviewers can follow the arc of your work in under a minute per piece. Here is a practical template you can adapt:

- Title of Project

- Short Statement (50–100 words) summarizing intent and outcome.

- Iteration Timeline (bulleted dates with one-line notes).

- Key Artifacts: 3–6 images or files showing stages (each with 1–2 line captions).

- Final Work: High-quality image/file with a 2–3 sentence reflection linking it to earlier iterations.

Example Timeline (Short)

2025-01-10: Concept sketches exploring identity symbols. 2025-02-01: Prototype with mixed media — texture too busy; simplified palette. 2025-03-12: Final composition — integrated motif from sketch #4; resolved texture with glazing technique.

Table: Quick Reference — What to Include by Portfolio Type

| Portfolio Type | Must-Have Iteration Evidence | Helpful Extras |

|---|---|---|

| AP 2-D Design | Thumbnails, color studies, material tests, composition reworks | Process gifs, breakdown of layering, stitching diagrams (if textile) |

| AP 3-D Design | Maquettes, armature photos, material tests, stability tests | Construction timelapse, engineering sketches |

| AP Drawing | Value studies, gesture sketches, progressive refinement photos | Close-ups of mark-making, comparative lighting studies |

| AP Capstone Research | Research question drafts, pilot study, revised methodology, annotated data | Code snippets, protocol versions, participant recruitment notes |

Common Pitfalls — and How to Avoid Them

Even with great work, weak presentation can undermine your submission. Here are common mistakes students make and quick fixes you can implement.

- Pitfall: Unlabeled images. Fix: Date and caption everything.

- Pitfall: Too many nearly identical steps. Fix: Select turning points — you don’t need every scribble.

- Pitfall: No reflection. Fix: Add 1–3 sentence captions explaining each change.

- Pitfall: Disorganized file structure. Fix: Use a single cloud folder with clearly named subfolders.

- Pitfall: Late documentation. Fix: Document as you go — set a weekly habit to photograph and annotate.

How Sparkl Can Help (Briefly and Naturally)

If you want guided support, personalized tutoring can make iteration documentation far easier. Working 1-on-1 with an expert tutor helps you identify which artifacts best tell your story, craft clear captions, and create a cohesive portfolio narrative. Tutors can offer tailored study plans and time-savers — for example, how to photograph work consistently or how to format an iteration timeline — and AI-driven insights can highlight gaps you might not notice alone.

Putting It Together: A Realistic Timeline for a Semester-Long Project

Here’s a sample schedule you can adapt if you’re working on a portfolio across a semester. This timeline creates natural checkpoints where iteration artifacts are produced and easy to document.

- Weeks 1–2: Inspiration and research; begin thumbnails and conceptual sketches.

- Weeks 3–4: Prototype phase — small studies and material tests; initial feedback session.

- Weeks 5–7: Revise prototypes; produce mid-scale versions and gather critique.

- Weeks 8–10: Major revisions informed by feedback; document the differences carefully.

- Weeks 11–14: Final execution and high-quality documentation; finalize captions and timeline.

- Week 15: Submission preparation — polish presentation and ensure all files are labeled and dated.

What To Do If You’re Starting Late

Don’t panic. Focus on producing a strong set of turning-point evidence rather than trying to manufacture dozens of staged steps. Quick, deliberate prototypes followed by reflective captions can still communicate iteration convincingly.

Assessment Mindset: Tell a Clear, Honest Story

Admissions and AP reviewers reward honesty and reflective thinking. Don’t try to hide failed attempts — those failures are often your best evidence of learning. Frame them as experiments that guided you to better decisions. A humble, clear narrative about what you tried and why you changed course is always stronger than a polished-looking but opaque submission.

Language to Use in Captions and Reflections

Here are a few short sentence starters that keep your reflections focused and reviewer-friendly:

- “I tried X because…, which revealed…”

- “After feedback indicating X, I adjusted Y to improve…”

- “The pilot showed…, so I revised my method to…”

- “This change allowed me to better express the idea of…”

Final Checklist Before You Submit

Run through this checklist to make sure your evidence of iteration is persuasive and complete.

- Do I have 3–6 meaningful artifacts per major piece showing development?

- Are all images and files labeled with dates and short captions?

- Do my captions explain the “why” behind changes, not just the “what”?

- Have I included both breadth (different approaches) and depth (evolution within an approach)?

- Are photographs clear, well-lit, and cropped thoughtfully?

- Have I saved a clean, well-organized folder for final submission with consistent filenames?

Closing Thoughts: Iteration Is a Strength, Not a Weakness

Showing iteration demonstrates that you are an active learner and maker. It’s evidence that you can test ideas, respond to feedback, and improve. Those are the exact skills AP teachers and college reviewers want to see. Whether you’re sketching in a studio or revising a research protocol, treat each step as part of a narrative you’re building. The artifacts you collect along the way will make your portfolio not just a display of talent, but a story of growth.

If you’d like help selecting which pieces best show your development, or want feedback on captions and organization, consider working with a tutor for tailored guidance. One-on-one sessions can clarify your narrative, fine-tune your visual documentation, and help you present iteration in the most compelling way possible.

Good luck — and remember: iteration is not an admission of imperfection; it’s the proof that you experimented, learned, and made your work better. That story is worth showing.

No Comments

Leave a comment Cancel