Why Causation vs Correlation Matters in AP History

If you’re preparing for AP History—whether it’s AP United States History, AP World History, or AP European History—you’ll notice an unshakable habit graders love to reward: clear, precise historical reasoning. At the heart of that reasoning is a deceptively simple distinction: causation versus correlation. Knowing how to tell them apart, when to argue for one or the other, and how to incorporate evidence effectively will raise the quality of your essays, DBQs, and short answers.

What These Terms Mean (In Plain English)

Start simple. Correlation means two things occur together or show a pattern. Causation means one thing directly contributes to or produces another. Correlation can hint at causation, but it doesn’t prove it. In history, people often see patterns and rush to causal claims. Your job is to be the patient investigator: gather evidence, weigh alternatives, and show the chain of reasoning that links cause to effect.

How AP Exams Expect You to Use These Skills

College Board rubrics—across LEQs, DBQs, and SAQs—reward nuanced thinking. That includes:

- Identifying multiple causes and distinguishing long-term vs short-term influences.

- Recognizing when patterns are coincidental or driven by third factors.

- Explaining mechanisms—how exactly a cause led to an effect.

- Using evidence to support causal claims and acknowledging limits where appropriate.

In short: graders want to see you think like a historian, not like a headline writer.

Simple Checklist Before You Claim Causation

- Is there a plausible mechanism linking A to B?

- Does the timing make sense? (Cause should precede effect.)

- Have you considered alternative explanations?

- Do sources support a direct link, or only show co-occurrence?

- Can you quantify or qualify the strength of the relationship?

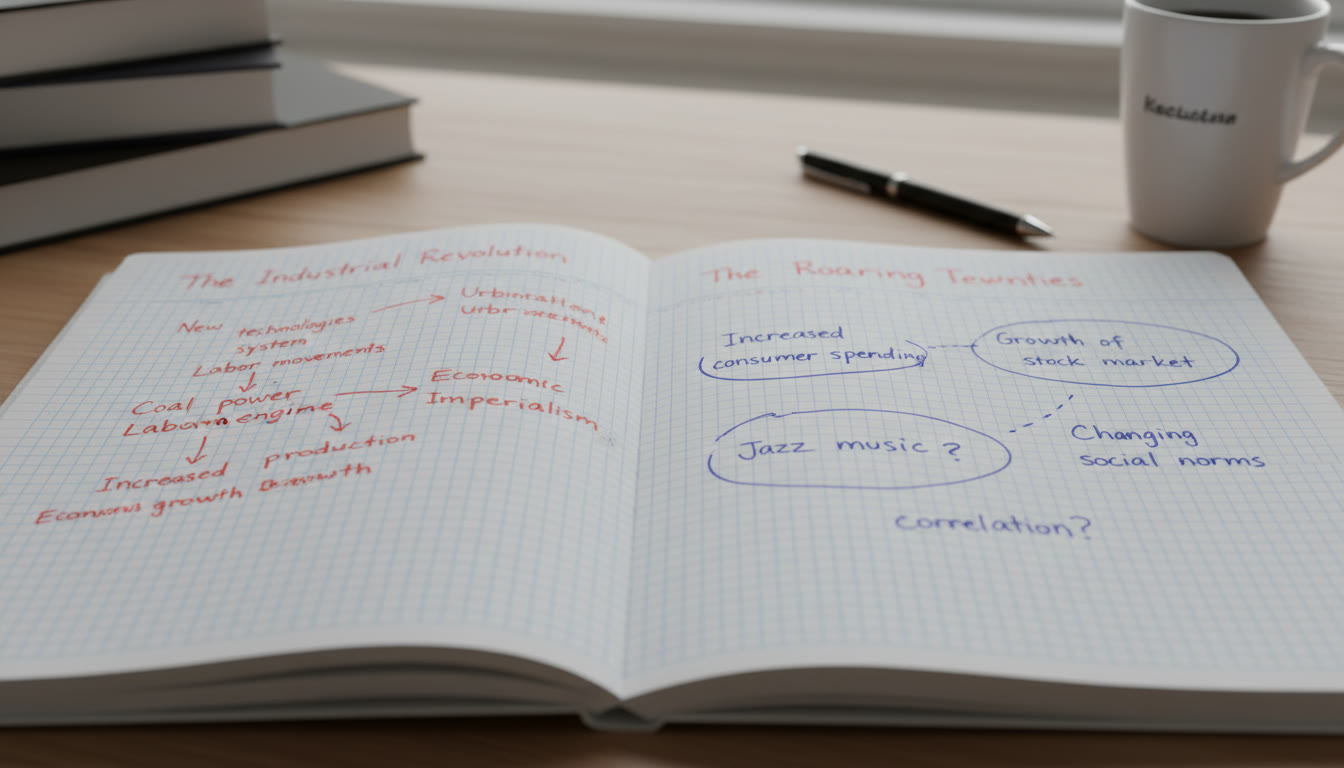

Examples That Clarify the Difference

Examples make the difference obvious. Below are three situational mini-cases you might encounter on the AP exams.

Example 1: Industrialization and Urban Crime

You notice that as industrialization increased in a city, recorded crime rates rose. Is industrialization the cause?

- Correlation alone: Both rise together—true.

- Potential causal story: Industrialization led to urban crowding, job displacement, and weakened community oversight, which contributed to higher crime.

- Alternative explanations: Improved policing and record-keeping might have simply increased the number of crimes recorded; migration could bring different social norms; economic cycles could be a hidden variable.

- What graders want: Mechanism + evidence (new housing conditions, police reports, or contemporary observers linking urban conditions to crime), plus awareness of alternatives.

Example 2: Disease Outbreaks and Religious Revival

A region experiences a major epidemic, and afterward you observe higher attendance at religious services. Is the epidemic the cause of the revival?

- Possible causal chain: Epidemic prompts existential questions, community gatherings, and searches for meaning—boosting religious participation.

- Other factors: Political upheaval, charismatic leaders, or economic support networks run by churches might explain the revival.

- Best response: Use personal narratives, sermons, and attendance records to establish timing and motivation, and qualify your claim by noting other reinforcing factors.

Example 3: Trade Expansion and Cultural Change

Trade routes expand and you see new art forms emerge. Is trade causing cultural change?

- Correlation exists: Goods and ideas flow along trade routes.

- Causal mechanism: Merchants and travelers bring materials, motifs, technologies, and tastes that artists adapt.

- Considerations: Local agency, selective adoption, and preexisting social structures shape how, whether, and why certain cultural changes take hold.

How to Structure an AP Essay Around Causation

Here is a practical paragraph structure you can use in a LEQ or DBQ when arguing causation. Keep it tight and explicit—examiners track clarity.

- Topic sentence: State the cause-and-effect claim clearly (what caused what?).

- Context: One or two sentences situating the claim historically.

- Mechanism explanation: Step-by-step description of how the cause produced the effect.

- Evidence: One or two specific pieces of evidence (documents, facts, statistics, or historians’ interpretations).

- Alternative explanation / qualification: Acknowledge limits or other contributing factors.

- Mini-conclusion: Reaffirm how the weight of evidence supports your causal claim.

Short Example Paragraph

Topic: The impact of the telegraph on 19th-century warfare.

“The telegraph significantly changed military command by enabling faster communication between headquarters and front lines, thereby increasing the speed of strategic coordination. Before the telegraph, orders relied on couriers and local discretion; with telegraphic lines, commanders could centralize decision-making and synchronize troop movements across distances. Contemporary military reports from the 1860s show earlier concentration of forces following telegraphic warnings, and military manuals adapted tactics to exploit quicker transmissions. Yet this shift did not eliminate delays caused by terrain or the fog of war, nor did it remove the need for reliable local reconnaissance—so the telegraph was an important causal factor, but not the sole determinant of battlefield success.”

Table: Quick Guide to Identifying Causation vs Correlation in Exam Tasks

| Exam Signal | What It Likely Requires | How to Respond |

|---|---|---|

| “Explain the reasons for” | Strong causal analysis (multiple causes) | List causes, explain mechanisms, prioritize, and cite evidence |

| “Analyze the relationship between” | Assess correlation and causation | Describe patterns, test causal links, acknowledge complexity |

| “Evaluate the extent to which” | Argue degree of causation | Weigh evidence for/against causation and give a judgment |

| “Compare” | Look for similarities/differences in causes or effects | Highlight shared mechanisms and distinct contexts |

Document-Based Questions (DBQs): Special Considerations

DBQs are a unique test of your ability to blend document evidence with outside knowledge. When documents show correlation, ask: do any documents provide a mechanism or first-person link between A and B? If not, use outside evidence to strengthen or qualify the causal claim.

- Group documents by the type of relationship they show (supporting causation, showing correlation, or offering counter-evidence).

- Use at least one document to demonstrate mechanism if possible.

- Explicitly explain why some documents show correlation only—perhaps because they record contemporaneous trends without analyzing cause.

Example DBQ Approach

Prompt: “Explain the causes of urbanization in the late 19th century and assess its consequences.”

Strategy: Use factory growth (cause) linked to rural-to-urban migration (mechanism: job opportunities), cite document about employment shifts, bring in outside knowledge about transportation improvements, then qualify urbanization’s consequences with evidence about housing and public health. Make sure to show which documents illustrate correlation (e.g., population and factory numbers increasing together) versus those that explain process (e.g., a labor recruiter’s letter describing incentives).

Common Pitfalls Students Make

- Confusing simultaneous events with causal chains. (Just because two things happened together doesn’t mean one caused the other.)

- Overusing single-source evidence to prove broad causal claims.

- Failing to specify the mechanism—answering “what” without the “how.”

- Ignoring counter-evidence or alternative explanations that would have strengthened their argument if acknowledged.

- Making anachronistic judgments—applying modern categories without historicizing them.

Practice Prompts and Model Responses

Practice is where nuance becomes habit. Here are two prompts and a brief model sketch for each.

Prompt A

“Explain the causes of the French Revolution, and evaluate the extent to which economic factors were more important than political factors.”

Model sketch: Identify economic causes (fiscal crisis, unequal taxation, food shortages) and political causes (Enlightenment ideas, royal authority failures). Explain mechanisms linking economics to unrest (bread prices spark popular protest) and show political mechanisms (parliamentary failure allowed radicals to mobilize). Conclude with a balanced judgment saying economics were central but political structures shaped outcomes.

Prompt B

“Analyze the relationship between imperial expansion and industrial growth in the 19th century.”

Model sketch: Note correlation (both expand in same period). Argue causation in both directions—industrial goods demand new markets (economic mechanism) and imperial resources feed industrial inputs (resource mechanism). Use specific examples (cotton, rubber) and qualify with local resistance and non-economic motives like strategic interests.

How to Practice Effectively (A Weekly Plan)

Consistency beats cramming. Below is a realistic weekly plan you can adapt:

- Day 1: Read a primary source and annotate for claims of cause or explanation.

- Day 2: Write a 20-minute mini-essay on a prompt testing causation vs correlation.

- Day 3: Peer-review or self-grade using the cause/mechanism checklist.

- Day 4: Do a timed DBQ focusing on grouping documents by relationship type.

- Day 5: Review feedback, revise one paragraph for stronger causal mechanism language.

- Weekend: Broader reading—secondary sources that model causal argumentation.

How Sparkl’s Personalized Tutoring Can Fit Into This Work

Targeted coaching can accelerate the learning curve. If you find yourself stuck—confusing correlation with causation, or struggling to craft a mechanism—tutoring that offers 1-on-1 guidance, tailored study plans, expert tutors, and AI-driven insights can give you focused feedback. A coach who reviews your essays, pushes you to justify links explicitly, and provides practice prompts aligned with AP rubrics can turn weak causal statements into compelling historical arguments.

Language and Phrases That Signal Strong Causal Thinking

Small vocabulary choices improve clarity. Use phrases that precisely indicate the relationship and degree of certainty:

- “Contributed to” (strong but not exclusive)

- “Facilitated” or “enabled” (mechanism-focused)

- “Coincided with” or “was associated with” (correlation language)

- “As a result of” (direct causal claim—use when you can show mechanism)

- “Partly due to” or “among the factors” (nuanced, hedged claims)

Self-Assessment Rubric (Quick)

After writing, check your paragraph against these three tiers:

- Basic: States cause and effect but no mechanism or evidence.

- Proficient: States cause, provides mechanism, and cites one piece of evidence.

- Advanced: Multiple causes prioritized, clear mechanism(s), multiple pieces of evidence, and acknowledgment of alternatives/limitations.

Final Tips: Think Like a Historian

At its heart, separating causation from correlation is about curiosity and rigor. Ask questions—how, why, when, and for whom? Don’t settle for surface patterns. Use the primary sources you have on the exam to establish timing and mechanism, bring in accurate outside knowledge, and always qualify your claims where evidence is ambiguous.

Keep a journal of causal claims you encounter in readings: note the claim, write down the proposed mechanism, list counter-evidence, and try to rank how convincing the claim is. Over time, your instinct for what needs proof and what can be asserted will sharpen.

Parting Thought

AP History exams reward students who balance confidence with humility—those who make claims but also show the limits of what the evidence can prove. Mastering causation versus correlation is less about memorizing a rule and more about developing a habit of careful inquiry. Practice deliberately, get feedback (whether from teachers, peers, or targeted tutoring like Sparkl’s personalized programs), and you’ll find your essays moving from “plausible” to persuasive.

Good luck—approach each prompt like a puzzle. The evidence is the map; your reasoning is the route. When you can show not just that events moved together but how and why they moved together, you’re thinking like a historian—and that’s exactly the skill AP graders are looking for.

No Comments

Leave a comment Cancel