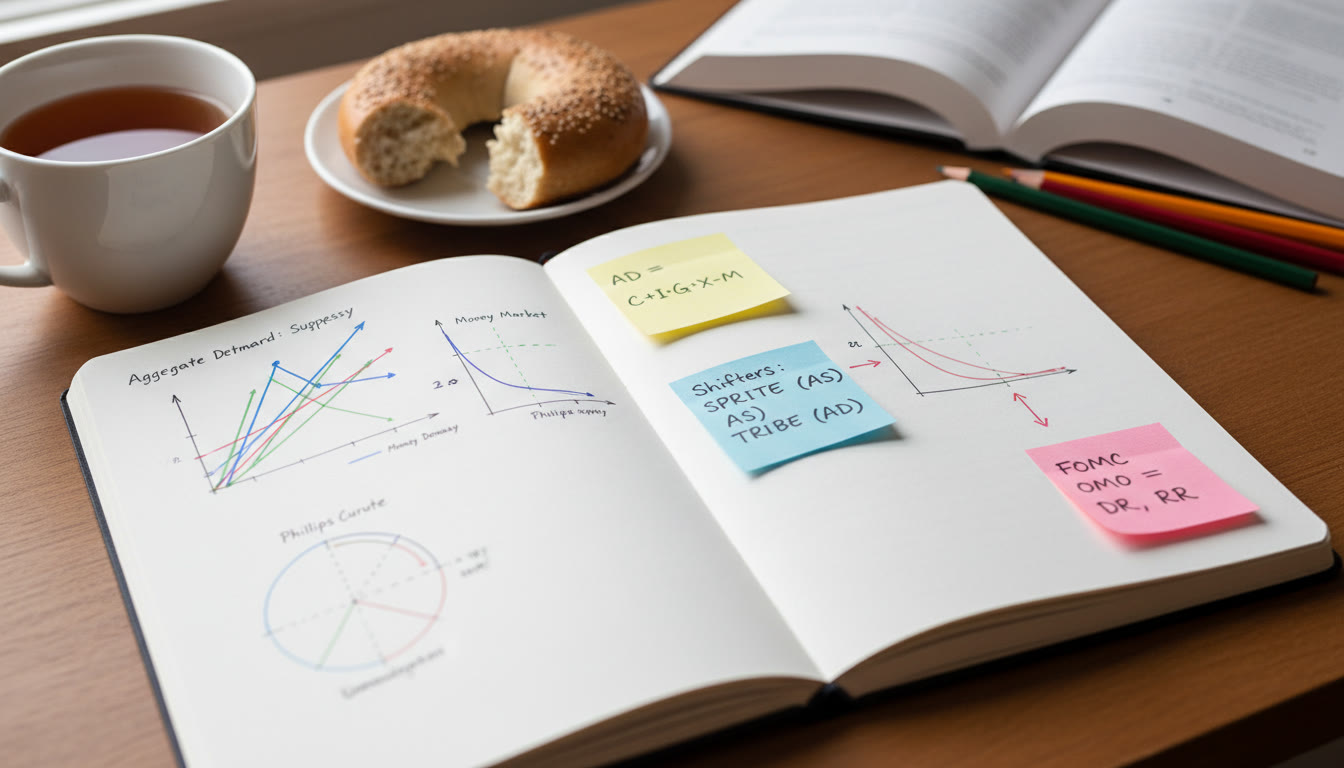

Why Graphs Matter in AP Macroeconomics

If you’re preparing for Collegeboard AP Macroeconomics, graphs are where the ideas come alive. The models — Aggregate Demand and Aggregate Supply (AD‑AS), the Money Market, and the Phillips Curve — are not just pictures you have to copy; they are visual stories about how an economy responds to shocks, policy, and expectations. This blog walks you through the mechanics of those graphs, gives practical tips for exam-style questions, and sprinkles in strategies that make studying efficient and even enjoyable. Where it fits naturally, I’ll mention how Sparkl’s personalized tutoring can help with one‑on‑one guidance, tailored study plans, expert tutors, and AI-driven insights to speed up your learning curve.

First Principles: What Each Graph Represents

Before you draw a single line, know the story each graph tells.

- AD‑AS Model: Shows the relationship between the overall price level and real output (Real GDP). AD slopes downward; SRAS slopes upward; LRAS is vertical at potential output.

- Money Market: Illustrates how the real interest rate is determined by money supply and money demand. Supply is vertical (set by the central bank); demand slopes downward in interest-rate terms.

- Phillips Curve: Connects inflation and unemployment. The short-run Phillips Curve (SRPC) slopes downward; the long-run Phillips Curve (LRPC) is vertical at the natural rate of unemployment.

How To Think About It

Each graph answers a “what if” question: what happens to output and prices if spending changes? If the Fed tightens? If productivity improves? As you study, convert prose into visuals. That conversion is the skill AP graders reward.

AD‑AS: Drawing and Interpreting Like a Pro

The AD‑AS model is the most commonly-tested graph in AP Macro. Let’s break the drawing and interpretation into repeatable steps.

Step 1 — Draw the Axes and Curves

Start with vertical axis = Price Level (P), horizontal axis = Real GDP (Y). Then add:

- AD — downward sloping (higher P → lower real spending).

- SRAS — upward sloping (higher P → firms produce more in the short run).

- LRAS — vertical at potential output (Y*), the economy’s natural level of output.

Step 2 — Label Everything Clearly

Label initial equilibrium where AD intersects SRAS as E0 with coordinates (P0, Y0). Mark Y* on the horizontal axis. If Y0 < Y* you’re in a recessionary gap; if Y0 > Y* you’re in an inflationary gap. These labels are small grade boosters.

Step 3 — Translate Policies and Shocks into Shifts

Memorize the most common shifts and WHY they occur.

- AD shifts right when: expansionary fiscal policy (increase G or cut taxes), expansionary monetary policy (increase money supply), rise in consumer confidence, or foreign demand for domestic goods rises.

- AD shifts left when: contractionary policy, drop in consumer confidence, or net exports fall.

- SRAS shifts right when: lower input prices (e.g., falling oil), improved productivity, or favorable supply shocks.

- SRAS shifts left when: cost-push shocks like rising wages or raw material costs.

Worked Example: Stimulus Check Scenario

Imagine the government sends stimulus payments to households. What happens in AD‑AS land?

- Direct effect: Consumption rises → AD shifts right (AD1).

- Short run: Higher real GDP and higher price level (movement from E0 to E1).

- Long run: If economy was at potential output already, higher AD creates upward pressure on prices; SRAS may shift left over time as wages and input costs adjust.

Common Pitfalls

- Forgetting to shift SRAS in the long run when shocks are persistent.

- Mixing up reasons for AD versus SRAS shifts — ask ‘does this change demand or aggregate supply?’

- Not labeling gaps (recessionary or inflationary). Exams love that language.

Money Market: Interest Rates and Policy Intuition

The money market is your bridge from the monetary authority to interest rates and investment — crucial for many AP questions that connect monetary policy to AD.

How to Draw It

Axes: vertical = Nominal Interest Rate (i), horizontal = Quantity of Money (M). The Money Supply (MS) is vertical (central bank sets it). Money Demand (MD) slopes downward because at lower interest rates people hold more money rather than bonds.

Interpreting Shifts

- Increase MS (open market purchases, lower reserve requirement) → MS shifts right → equilibrium i falls → investment increases → AD shifts right (through higher I).

- Decrease MS (open market sales, higher reserve requirement) → MS shifts left → i rises → investment falls → AD shifts left.

- Money Demand shifts right if income rises or price level increases (demand for nominal balances rises).

Worked Example: Fed Tightening

If the Fed sells government bonds to the public, MS falls (left). Interest rates rise, borrowing costs increase, investment and consumption decline, and AD shifts left. On AD‑AS, you’d show AD moving left and the new equilibrium at a lower Y and lower P — simple chain of causality to practice for the exam.

Phillips Curve: Tying Inflation and Unemployment Together

The Phillips Curve helps you reason about short-run trade-offs and long-run neutrality.

Draw and Label

Axes: vertical = Inflation Rate (π), horizontal = Unemployment Rate (u). SRPC slopes downward: lower unemployment tends to be associated with higher inflation in the short run. LRPC is vertical at the natural rate of unemployment (u*).

How Expectations Fit In

Expectations about inflation shift the SRPC. If expected inflation rises, the SRPC shifts up; if expected inflation falls, SRPC shifts down. That’s why policies that try to exploit a short-run trade-off (e.g., stimulate AD to lower unemployment) can backfire when expectations adjust.

Worked Example: Demand-Pull Inflation

If AD increases, unemployment falls and inflation rises — movement along the SRPC up and left. Over time, as people expect higher inflation, the SRPC shifts up and unemployment returns toward u*, leaving higher inflation — the classic expectation-augmented Phillips story.

Bringing the Graphs Together: Chains of Reasoning

AP questions often require you to move from one graph to another: change in the money market → interest rate change → AD shift → AD‑AS equilibrium change → movement along Phillips Curve. Practice linking them in a chain of causation. Here’s a concise table you can memorize and use as a quick-check in exam conditions.

| Initial Change | Immediate Graph Affected | Direction | Secondary Effects |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fed buys bonds | Money Market | MS → Right | i ↓ → Investment ↑ → AD → Right → Y ↑, P ↑ → Movement on SRPC: u ↓, π ↑ |

| Oil price spike | SRAS | SRAS → Left | Y ↓, P ↑ (stagflation) → SRPC shifts up over time if expectations adjust |

| Tax cut | AD | AD → Right | Y ↑, P ↑ → u ↓ temporarily → possible upward pressure on inflation |

Exam Tips: How to Earn Points on Graph Questions

- Always draw full initial and final equilibriums and label points (E0, E1), price levels (P0, P1), and outputs (Y0, Y1).

- State the direction of the shift explicitly in words — “AD shifts right because consumption rises.” Don’t rely on the drawing alone.

- When asked for short-run and long-run effects, show both: immediate shift on SRAS/AD and later adjustment (SRAS shifting back, or expectations shifting the SRPC).

- If a question includes numerical values, do the arithmetic and show the updated coordinates — graders like clarity.

- Practice a few standard scenarios until the causal links are second nature — you’ll save time on test day.

Study Routine: Turning Practice into Mastery

Graphs improve fastest through targeted, repeated practice. Here’s a weekly plan that students often find effective.

- Day 1: Concept review — read a concise summary of AD, SRAS, LRAS, money market, and Phillips Curve.

- Day 2: Draw 10 graph variations from memory (label everything) — include demand shocks, supply shocks, monetary tightening and loosening.

- Day 3: Timed practice — do 2 AP-style free-response questions focused on graphs. Time yourself and grade against rubric expectations.

- Day 4: Error analysis — review mistakes, rewrite correct answers, and make a one-page cheat sheet of common shifts and their reasons.

- Day 5: Mixed questions — link money market to AD‑AS to Phillips Curve in chain problems.

- Weekend: Tutoring or peer review — explaining the concept to someone else is one of the best ways to internalize it. Sparkl’s personalized tutoring can be particularly helpful here: a tutor can quickly identify misconceptions and tailor practice problems to your weak spots.

Practice Problem Walkthrough

Let’s do an AP-style scenario step by step.

Prompt: The central bank announces a permanent increase in the money supply. Explain the short-run and long-run effects on the money market, AD‑AS, and the Phillips Curve.

Short‑Run Steps

- Money Market: MS shifts right → nominal interest rate falls.

- AD‑AS: Lower interest rates raise investment and consumption → AD shifts right → output (Y) increases and price level (P) increases.

- Phillips Curve: Movement along the SRPC to lower unemployment and higher inflation.

Long‑Run Steps

- Because the increase is permanent, people will start expecting higher inflation. Expected inflation rises.

- SRAS shifts left as wages and input prices adjust to higher expected inflation, bringing real output back to potential (Y*), but at a higher price level.

- On the Phillips Curve, the SRPC shifts up — unemployment tends back to u* while inflation remains higher.

Visual Memory Hacks

Students often ask: how do I remember which way each curve shifts? Use imagery and short phrases:

- AD: “Spending moves the AD” — think consumers, investors, government, and net exports pushing the entire demand for goods and services.

- SRAS: “Costs move SRAS” — anything that raises production costs shifts SRAS left.

- LRAS: “Potential, not price” — LRAS is vertical because long-run output depends on resources and technology, not price level.

- Money Market: “Fed sets supply, people choose demand” — vertical MS, downward MD.

- Phillips: “Short-run trade, long-run no free lunch” — SRPC slope; LRPC vertical.

How Sparkl’s Personalized Tutoring Can Fit Into Your Prep

Personalized help can accelerate mastery. If you struggle with specific graph transitions — say, mapping a monetary policy action through the money market into AD‑AS and then onto the Phillips Curve — targeted one‑on‑one sessions can help. Sparkl’s personalized tutoring offers tailored study plans and expert tutors who can give immediate, focused feedback. They can simulate timed FRQ practice and use AI-driven insights to highlight the patterns in your mistakes so you fix the root cause instead of the symptom.

Sample Quick-Reference Cheat Sheet (One Page)

Keep this cheat sheet on a single card for last-minute review.

| Action | Immediate Shift | Short-Run Effect | Long-Run Effect |

|---|---|---|---|

| Expansionary Fiscal Policy | AD → Right | Y ↑, P ↑, u ↓ | Possible SRAS leftward adjustment if persistently above Y* |

| Contractionary Monetary Policy | MS → Left | i ↑ → Investment ↓ → AD → Left; Y ↓, P ↓, u ↑ | Lower inflation expectations may shift SRPC down over time |

| Supply Shock (e.g., Oil Rise) | SRAS → Left | Y ↓, P ↑ (stagflation) | Depends on persistence; can raise expected inflation if sticky |

Final Tips: Confidence, Not Just Cramming

Graphs reward clarity. Practice deliberately: draw, explain out loud, and connect the steps. When you make errors, correct them immediately and add a one-sentence rule to your cheat sheet so you avoid repeating the same mistake. If your schedule allows, one-on-one sessions with a tutor to target your misconceptions can be a fast route to consistent scores — Sparkl’s approach to personalized tutoring and AI feedback is designed to do that without wasting your time.

Conclusion: Make the Graphs Tell the Story

AD‑AS, the Money Market, and the Phillips Curve are three lenses through which you can interpret macroeconomic events. The secret to AP success is turning abstract statements into visual moves: decide which curve shifts, draw the before-and-after, and explain why in simple causal language. With targeted practice, a compact cheat sheet, and occasional personalized tutoring to iron out sticking points, these graphs will go from confusing to second nature — and that’s where real exam confidence comes from.

Good luck studying. Draw often, explain clearly, and remember: the story behind the lines is what graders want to see.

No Comments

Leave a comment Cancel