Why Seminar Team Dynamics Matter

AP Seminar and any high-level classroom that prizes discussion, evidence-based argument, and collaborative projects relies on more than brilliant ideas. It relies on people. The way a team negotiates disagreement, assigns roles, and reaches shared conclusions determines not only the quality of the final deliverable but also what each member learns along the way. For students aiming to excel in AP Seminar, mastering team dynamics—especially transforming conflict into consensus—is a skill as important as citing sources or crafting claims.

From Conflict to Consensus: Not a Destination but a Process

Conflict isn’t the enemy. It can be the engine of creativity. Consensus is less about everyone saying “yes” and more about everyone saying “I can live with this because my concerns were heard.” In seminar settings, conflict often arises from different interpretations of evidence, different rhetorical priorities, or uneven workload expectations. Turning that tension into a stronger product requires mindset, structure, and deliberate communication.

Common Sources of Tension in Seminar Teams

- Unequal participation: Some students dominate discussion while others stay silent.

- Clashing priorities: One student emphasizes rhetoric, another wants deeper epistemology.

- Conflicting work habits: Different conceptions of timelines, drafts, and revision.

- Ambiguous roles: Nobody clearly owns synthesis, citation checking, or presentation design.

- High emotional stakes: AP scores, college aspirations, and peer relationships all raise the temperature.

A Short Table: How Tensions Typically Appear and What They Signal

| Symptom | Probable Root Cause | Quick Intervention |

|---|---|---|

| One person dominates discussion | Lack of structure, comfort with speaking | Introduce timed turns or a talking piece |

| Repeated missed deadlines | Unclear expectations or overload | Reassign tasks, set micro-deadlines |

| Resentment about quality of contributions | Different standards or skills gaps | Peer review rubric and transparent revision rounds |

| Stalemate over an interpretation | Strong, competing evidence-based positions | Devil’s advocate round, then synthesis mapping |

Foundational Habits That Prevent Harmful Conflict

Before conflict needs to be repaired, many problems can be prevented by establishing healthy habits early. Here are practical habits teams can start using from week one:

- Define success together: Spend 10–15 minutes at the first meeting describing what a successful project looks like. Agree on standards for research depth, citation, and presentation polish.

- Create a simple working charter: Include roles, communication norms, expected response times, and a conflict-resolution pathway (e.g., first talk it out, then escalate to teacher or mediator).

- Use micro-deadlines: Instead of one looming due date, schedule small deliverables. Micro-deadlines reduce last-minute stress and make accountability kinder.

- Rotate roles: Have everyone try being the synthesizer, the evidence tracker, the presenter. Role rotation builds empathy and shared skill sets.

- Adopt a shared rubric: If possible, create or agree upon a grading rubric you’ll use for peer review—this focuses critiques on agreed standards rather than personalities.

Practical Communication Rules

- Speak from experience: Use “I” statements (“I’m worried this claim lacks evidence”) rather than accusatory “You” statements.

- Ask clarifying questions before arguing (“Can you explain how you matched that source to the claim?”).

- Be explicit about preferences vs. requirements (“I prefer a conciser intro, but I’ll follow the team’s decision”).

- When emotions run high, pause. Take a scheduled 10-minute break and reconvene with a goal-focused agenda.

Diagnosing Conflict: A Short Toolkit

When conflict appears despite preventive measures, treat it as data to be interpreted rather than proof of irreconcilable differences. Use this mini-toolkit to diagnose where the issue sits:

- Scope: Is the dispute over content (evidence, claim), process (deadlines, roles), or interpersonal dynamics?

- Temperature: Are reactions calm and reasoned, or emotional and reactive?

- Frequency: Is this a one-off disagreement or a recurring pattern?

- Stakeholders: Who will be affected by the resolution? Sometimes a compromise that satisfies most is acceptable; other times, a teacher’s arbitration is needed.

Step-by-Step Repair Process

Repairing a broken conversation is easier when you agree on steps. Here’s a simple sequence teams can use:

- Pause and name the issue: One person summarizes the disagreement neutrally.

- Share perspectives: Each member gets 2–3 uninterrupted minutes to state their view and why it matters.

- Map common ground: Use a whiteboard or shared doc to write overlapping beliefs and constraints.

- Generate options: Brainstorm at least three ways forward, even wild ones.

- Choose and timebox: Pick an option, set a short trial period, and agree how you’ll evaluate it.

- Reflect and iterate: After the trial, review what worked and what didn’t.

Techniques to Build Consensus—Fast

Consensus doesn’t require unanimity, but it does require a method that respects dissent while moving the group forward. Below are techniques you can use during seminar prep, evidence rounds, or final synthesis.

- Fist to Five: Quick show-of-hands method where 0 (fist) = strong objection, 5 = full support. If someone shows 0–2, ask them to explain their concern and work to address it.

- Weighted Voting: Each member has a set number of points to allocate to proposals. This can balance influence when confidence levels differ.

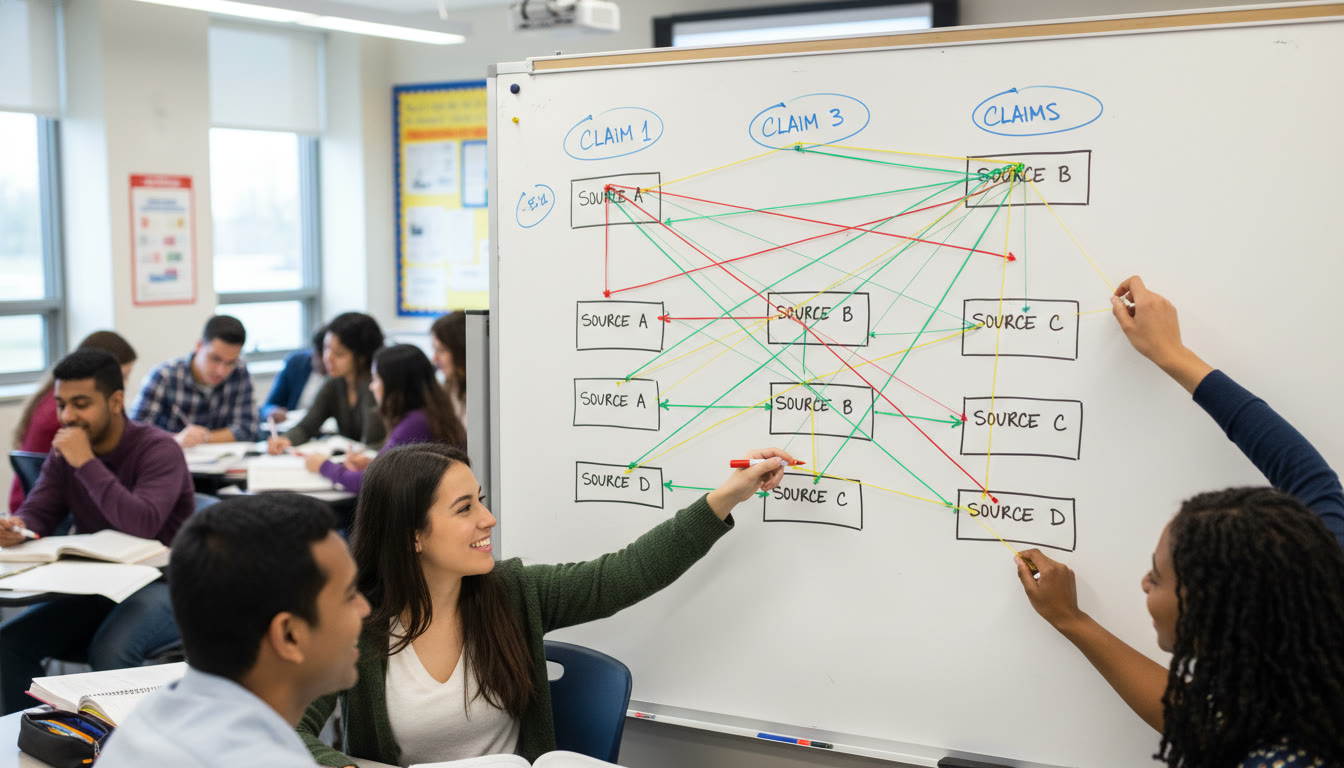

- Evidence Mapping: Create a visible map that places evidence next to claims. If a claim lacks evidence, consensus often shifts toward rewording rather than insisting on the original claim.

- Devil’s Advocate Round: Assign one person to critique the group’s favored position—temporarily. This surfaces weaknesses in a low-stakes way.

- Draft-and-Respond: One member drafts a synthesis section, the team annotates with track changes or margin notes, then reconvenes to negotiate major edits.

Example: Resolving a Stalemate Over an Interpretation

Three students disagree on whether a primary source implies intentionality or accident. Apply the repair sequence: name the issue, each states the evidence they prioritize, map overlaps (both agree the source shows event X), generate options (split the claim into two, acknowledge ambiguity, or collect more sources), choose (acknowledge ambiguity in the synthesis), and timebox (assign one person 48 hours to find corroborating evidence). This approach avoids a binary win/lose and improves the final product’s nuance.

Roles and Responsibilities: A Sample Team Contract

Teams that write a short contract—one paragraph to one page—avoid many disputes. Here’s a sample template you can adapt:

- Project goal: What we want to accomplish by the rubric’s standards.

- Roles: Research Lead, Evidence Checker, Synthesis Writer, Presenter, Editor.

- Communication: Slack or Google Chat for quick items; email for final drafts; 24-hour response expectation on school days.

- Deadlines: Micro-deadlines with responsible person listed.

- Conflict process: Try pairwise resolution, then group mediation, then teacher mediation.

Table: Sample Role Breakdown With Time Commitments

| Role | Main Tasks | Estimated Weekly Time |

|---|---|---|

| Research Lead | Source discovery, initial annotations, source log | 4–6 hours |

| Evidence Checker | Verify citations, extract quotes, cross-check claims | 2–4 hours |

| Synthesis Writer | Draft organized argument, integrate evidence | 3–5 hours |

| Presenter | Create slides, rehearse talk, manage Q&A prep | 2–4 hours |

| Editor | Polish prose, check transitions and citations | 1–3 hours |

Practical Tools and Routines That Help

Teams that adopt simple, consistent tools and routines reduce friction. Here are actionable suggestions:

- Shared source document: One living Google Doc or equivalent where everyone logs sources with short annotations and relevance notes.

- Structured meeting agendas: Start with 5 minutes of wins, 10 minutes of blockers, 20 minutes of work. End with assigning micro-deadlines.

- Two-minute check-ins: At the start of each meeting, each person states their top priority and one roadblock.

- Revision windows: Have two separate windows—content revision (big moves) and line editing (polish)—so debates focus only on what’s relevant to each stage.

How Tutoring and Tailored Support Fit In

Sometimes the disagreement in a team isn’t interpersonal at all—it’s technical. Maybe no one knows how to evaluate a quantitative study’s methods, or the group struggles with rhetorical moves. That’s when targeted support helps. Personalized tutoring—like Sparkl’s 1-on-1 guidance and tailored study plans—can quickly raise the team’s baseline, giving members specific strategies to assess evidence, refine arguments, and improve presentation technique. A short tutoring intervention can transform uncertainty into confidence and make consensus easier to achieve because skill gaps are addressed rather than argued about.

Facilitating Inclusivity: Making Every Voice Count

Consensus is only meaningful if inclusion is real. Consider these techniques to ensure quieter voices are heard and power dynamics don’t skew outcomes:

- Silent brainstorming: Give five minutes of writing before discussion. This levels the playing field for idea generation.

- Round-robin sharing: Go around the table so each member answers a focused question.

- Anonymous feedback: Use short, anonymous forms to surface critiques that members might feel uncomfortable voicing in person.

- Pair-and-share: Let members first discuss in pairs, then share with the whole group—this reduces pressure.

Real-World Context: Why These Skills Matter Beyond AP

Learning to transform conflict into consensus is a life skill. On college campuses, in internships, in workplaces, and in civic life, the ability to negotiate differing perspectives, synthesize evidence, and build agreements is invaluable. AP Seminar intentionally simulates those high-stakes contexts—so students who learn robust team dynamics not only do better on assessments but also enter college ready to contribute meaningfully to group-based projects.

Practice Exercises to Build Consensus Muscles

Here are repeatable exercises teams can use to improve their dynamics without the pressure of a graded project.

- Claim Swap: Each member writes a one-sentence claim. Swap claims and write counter-evidence. Reconvene to find synthesis that honors both claims.

- Two-Minute Teach: Each student teaches the team one skill—how to read a figure, how to annotate a source—then the team applies it immediately.

- Silent Synthesis: Give the team 20 minutes to silently write a shared paragraph. Compare drafts to reveal differences in priorities and phrasing.

- Mini-Mediation: Practice the repair sequence on a staged disagreement. Rotate mediators and reflect on what language helped calm the room.

When to Involve the Teacher or an External Mediator

Most disputes can be solved internally, but some situations need outside help:

- Repeated breaches of the team charter (e.g., chronic missed deadlines).

- Clear evidence of academic dishonesty or plagiarism concerns.

- Interpersonal issues that escalate beyond productive classroom interactions (persistent disrespect, harassment).

- When a technical skill gap prevents progress and no internal member can reasonably cover it—this may be a moment to ask for teacher-led instruction or brief tutoring support.

How to Ask for Help Productively

Teachers are more likely to help when requests are clear. Frame the ask with what you’ve already tried, where you’re stuck, and what outcome you hope for. Example: “We’ve tried rotating roles and creating micro-deadlines, but two members still miss work. Can you help mediate a meeting and suggest consequences that align with class policy?”

Wrapping Up: A Culture Over Checklist

Practical tools are critical, but what makes teams resilient is culture: a shared belief that disagreement is an opportunity, that critique is about improving the work not attacking a person, and that every member is accountable. Spend time building that culture. Celebrate small wins. Reflect after each deliverable about what worked in your collaboration and what to change.

Final Checklist Before Submission or Presentation

- Do all claims have clear, traceable evidence?

- Has the team completed at least one round of peer review using a shared rubric?

- Are roles and contributions documented in a final project log?

- Has the team rehearsed presenter Q&A and decided who answers which kinds of questions?

- Did you conduct a brief retrospective: what to keep, what to change for next time?

Seminar team dynamics are an iterative learning space. By treating conflict as information, adopting simple structure, practicing inclusive communication, and seeking targeted help when needed—whether that’s a teacher’s mediation or a short burst of personalized tutoring like Sparkl’s 1-on-1 guidance—students can transform tense moments into smarter, more persuasive consensus. The project you submit will be stronger, and the skills you take away will be useful long after the AP score arrives.

Parting Thought

Great seminar teams aren’t flawless; they’re curious, accountable, and courageous enough to disagree openly. Make a practice of listening as an instrument for discovery rather than a prelude to a rebuttal. Do that, and you’ll find consensus isn’t a forced compromise—it’s a stronger idea that survived scrutiny.

No Comments

Leave a comment Cancel