Why the Conclusion Matters More Than You Think

In AP Statistics FRQs, the conclusion is your final handshake with the reader — the grader. It’s where all the calculations, graphs, and tough interpretations meet the practical question: what do these results actually mean? A precise, well-worded conclusion can often be the difference between a partial and a full score on the inference portion.

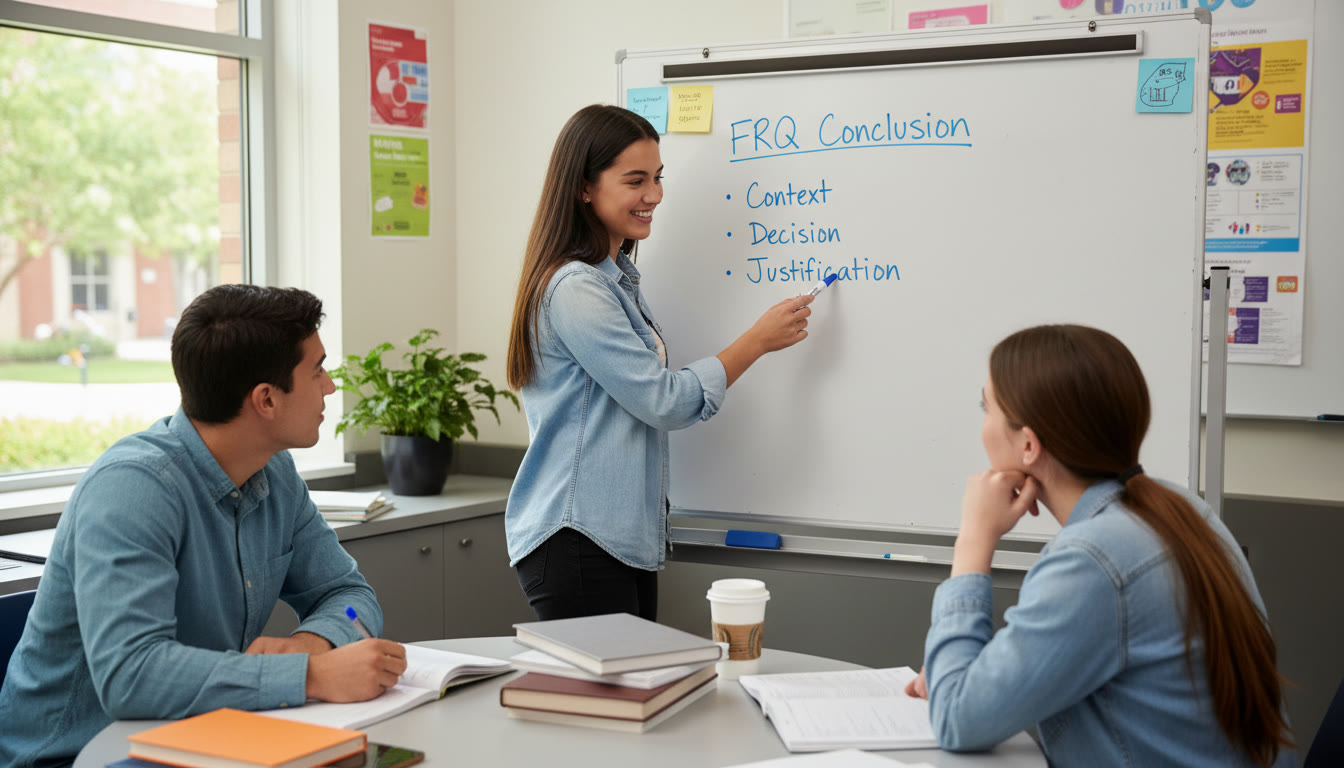

What graders are looking for

When a grader reads your conclusion they check for three core elements: context, decision (or estimate), and justification (linking the decision to the evidence). If your conclusion clearly contains these elements and uses correct statistical language, you’ve put yourself in a great position to earn full points.

- Context: Reference the variables and the practical question — nothing generic like “there is evidence.”

- Decision/Estimate: If it’s hypothesis testing, explicitly state whether you reject or fail to reject H0. If it’s a CI, give the interval and interpret in context.

- Justification: Tie your decision to the p-value, test statistic, or the interval and state the significance level (commonly 0.05 unless told otherwise).

Simple Templates That Work

Templates are not cheats — they’re tools. Use them as frameworks and then customize with context and numbers.

Hypothesis Test (two-sided)

Template:

- “At the 0.05 significance level, we [reject/fail to reject] the null hypothesis. There is [sufficient/insufficient] evidence to conclude that [contextual statement about the parameter].”

One-sided Test

- “At α = 0.01, we [reject/fail to reject] H0. The data provide [strong/little] evidence that [parameter] is [greater/less] than [value].”

Confidence Interval

- “A 95% confidence interval for [parameter] is [lower, upper]. We are 95% confident that the true [contextual parameter] is between [lower] and [upper].”

Language: Precise Words That Keep You Safe

The AP graders are strict about statistical vocabulary. Small word choices can cost points.

- Say “fail to reject” rather than “accept” the null hypothesis.

- Use “evidence” rather than “proof” — statistics never proves.

- When describing confidence intervals, say “We are 95% confident” (referring to the method), and then interpret in context about the parameter (not the sample).

- When mentioning p-values, reference the significance level: “p = 0.03 < 0.05, so reject H0.”

Common Pitfall: Overstating

Statements like “This proves that coffee causes better grades” are wrong. Cause-and-effect claims require randomized experiments with controlled design. In observational settings, stick to words like “associated with” or “related to,” and always point back to the study design.

Example Walkthrough: Hypothesis Test That Scores Well

Let’s walk through a clear, point-earning conclusion for a sample FRQ.

FRQ setup (short): A researcher tests whether a new tutoring program changes average test scores. Randomized sample of students: sample mean = 82.5, hypothesized mean = 80, sample SD = 6.0, n = 36, α = 0.05. Calculated t = 2.5, p ≈ 0.016.

Calculations (brief)

We won’t re-derive the t here — assume your computations are shown neatly on the FRQ. The key for the conclusion is to mention the α level, the p-value or test statistic, and tie it into context.

Strong Conclusion Example

“At the 0.05 significance level, we reject the null hypothesis (t = 2.5, p ≈ 0.016). There is sufficient evidence to conclude that the tutoring program changes the average test score; the sample suggests an increase in mean score from 80 to about 82.5. Because this was a randomized experiment, the difference is consistent with a causal effect of the tutoring program.”

Why this works:

- It names the significance level and decision (reject H0).

- It reports the test statistic and p-value to justify the decision.

- It states the result in context and — because the scenario specified random assignment — responsibly suggests causality.

Example Walkthrough: Confidence Interval Interpretation

Suppose a 95% CI for the difference in proportions of two groups is (0.03, 0.12).

Strong conclusion:

“A 95% confidence interval for the difference in proportions is (0.03, 0.12). We are 95% confident that the true difference in proportions (Group A minus Group B) is between 0.03 and 0.12. Because the interval does not contain 0, this provides evidence that the proportions differ, with Group A having the higher proportion.”

This conclusion states the CI, interprets confidence correctly, references the parameter, and connects to statistical significance via the interval excluding 0.

Quick Checklist: Earn the Inference Points

| Item | What to Include | Why It Matters |

|---|---|---|

| Context | Name the variable and the population or groups. | Shows the grader you answered the question asked. |

| Decision / Estimate | State “reject/fail to reject” or give the CI with endpoints. | Directly corresponds to scoring rubric points. |

| Numerical Justification | Give p-value/test statistic or interval and α. | Connects the math to the conclusion. |

| Proper Language | Use “evidence,” “associated,” “fail to reject,” not “prove.” | Prevents loss of points for imprecise or incorrect terms. |

| Design-based Claims | Only claim causality for randomized experiments. | Shows understanding of study limitations. |

How to Tailor Conclusions to Different FRQ Types

Comparing Means or Proportions

Always specify which group you reference and the direction of the effect. E.g., “Group 1 has a higher mean than Group 2” or “the proportion in the treatment group is about 8% higher.” Quantify when possible.

Regression Contexts

State the interpretation of the slope in context (e.g., “For each additional hour studied, predicted score increases by 2.1 points on average”). For hypothesis tests about slope, follow with reject/fail to reject and link to p-value.

Chi-Square Tests

Report the test decision and say whether variables appear independent or not. Avoid causal language unless the design supports it. Example: “The chi-square test (χ2 = 10.4, p = 0.0013) indicates evidence of association between gender and preference.”

Putting It All Together: A Model Answer

Imagine an FRQ that asks whether a new study habit program increases the proportion of students who meet a target grade. After calculations, your results: p = 0.042, α = 0.05, sample proportion increase ≈ 0.07.

A model conclusion that hits all points might read:

“At the 0.05 significance level, we reject the null hypothesis (p = 0.042). There is sufficient evidence to conclude that the study habit program increases the proportion of students meeting the target grade; the observed increase is about 0.07. Because the students were randomly assigned to the program, this result is consistent with a causal effect.”

Notice how this short paragraph contains context (study habit program, proportion meeting target), decision with α and p-value, an estimate, and a justified causal claim because the design supports it.

Common Mistakes and How to Avoid Them

- Mixing up the sample and parameter. Always refer to the parameter in the conclusion (“true mean,” “population proportion”), not the sample statistic.

- Saying “statistically significant” without stating direction or practical importance. If the effect is tiny, say so: “statistically significant but practically small.”

- Leaving out the significance level. If the question gives α, include it in your conclusion.

- Using absolute words like “prove,” “definitely,” or “for sure.” Avoid them.

Tip: Short but Complete

Examiners love concise clarity. A one- or two-sentence conclusion that contains the checklist items is better than a long paragraph that obfuscates what you actually concluded.

Practice Prompts and Model Conclusions

Try writing conclusions for the prompts below and compare to the model answers. Practice both a fast version (30–60 seconds) and a careful version (2–3 minutes).

- Prompt: A randomized trial tests whether daily puzzles improve test scores. Result: p = 0.22, α = 0.05. Model: “At α = 0.05 we fail to reject H0 (p = 0.22). There is insufficient evidence to conclude that daily puzzles change average test scores.”

- Prompt: Observational study finds 95% CI for difference in means is (-1.8, 0.4). Model: “A 95% CI for the difference in means is (-1.8, 0.4). We are 95% confident that the true difference is between -1.8 and 0.4. Because the interval contains 0, the data do not provide evidence of a difference between the groups.”

How to Practice Efficiently — A Weekly Plan

Consistency beats marathon cramming. Here’s a simple weekly plan to sharpen your FRQ conclusions.

- Day 1: Review hypothesis/conclusion language; memorize templates.

- Day 2: Practice 3 short inference FRQs under time; focus on writing the conclusion first.

- Day 3: Do one long FRQ and self-score using the checklist table above.

- Day 4: Learn from mistakes — rewrite weak conclusions into strong ones.

- Day 5: Timed set — 4 short FRQs, 10 minutes each; aim for crisp conclusions.

- Weekend: Full practice exam or a longer timed FRQ section to simulate fatigue.

Real-World Context: Why Clear Conclusions Matter Beyond the Exam

In the real world, you will be asked to interpret data for non-statisticians — teachers, managers, or the public. Writing a conclusion that states the decision, explains the context, and quantifies the effect is a professional skill. Whether you’re pitching an idea, writing a lab report, or designing a survey, these habits will make your findings useful and trustworthy.

When to Get Extra Help

If you find yourself repeatedly losing points for language or for tying the math to context, it helps to get targeted feedback. 1-on-1 guidance can quickly point out patterned mistakes — for example, confusing sample vs. population language or habitually misinterpreting p-values. Sparkl’s personalized tutoring offers tailored study plans, expert tutors, and AI-driven insights that can zero in on those recurring issues and give you practice prompts aligned with AP rubrics. Coaching that focuses on feedback and iteration will move your conclusions from “good” to “full credit” faster than solo practice alone.

Final Checklist Before You Hand In Your FRQ

- Have you named the parameter/population? (Yes/No)

- Did you state the decision (reject/fail to reject) or provide the CI? (Yes/No)

- Did you include α, p-value, or test statistic when relevant? (Yes/No)

- Did you interpret the results in context using correct vocabulary? (Yes/No)

- If claiming causation, does the study design support it? (Yes/No)

One Last Example — A Polished Final Paragraph

“At the 0.05 significance level, we reject the null hypothesis (t = -2.1, p = 0.038). The data provide sufficient evidence that the new diet plan is associated with a decrease in average cholesterol; the sample indicates a decrease of about 12 mg/dL. Because the participants were not randomly assigned in this observational study, we cannot definitively claim causation.”

This paragraph is short, precise, and shows that the writer understands both the statistical result and the limitations of the study design.

Wrapping Up — Confidence With Clarity

Writing conclusions for AP Stats FRQs is a learned craft. Use the templates, follow the checklist, be precise with language, and always tie your decision to the evidence. With consistent practice you’ll gain speed and clarity.

And if you want feedback that accelerates that process, consider focused tutoring: tailored study plans and guided practice sessions help you fix recurring issues quickly. Sparkl’s personalized tutoring and AI-driven insights can be a useful boost if you want targeted improvement on writing inference conclusions that consistently earn full points.

Now, take out a past FRQ, circle the conclusion section, and rewrite it using the frameworks above. You’ll be surprised how quickly your conclusions become examiner-friendly — succinct, accurate, and worthy of full credit.

Good luck — clear thinking, clear words, full points.

No Comments

Leave a comment Cancel