Introduction — Why “Sure Points” Matter

If you’ve ever stared at a Humanities Free Response Question (FRQ) and felt your brain short-circuit, you are not alone. Humanities FRQs—spanning AP English Literature, AP United States History, AP European History, and AP Human Geography—test not only what you know but how quickly and convincingly you can express it. That’s where “sure points” come in: the dependable, high-value moves you can make in any FRQ to lock in points early and often.

This post is written for students who want to transform exam anxiety into a plan. We’ll break down what sure points are, where to place them within your response, and concrete language and structural choices that consistently earn points from readers and graders. Expect templates, a sample rubric-checklist, timing strategies, and a realistic sample answer. If you want personalized help turning this into practice-ready skills, Sparkl’s personalized tutoring (1-on-1 guidance, tailored study plans, and AI-driven insights) can be a great complement to your practice—but only when it fits your learning style and schedule.

What Are “Sure Points”?

“Sure points” are clear, defensible pieces of content you can reliably produce under exam conditions that are likely to earn credit. They are not flashy—often they’re straightforward factual claims, explicit thesis sentences, or short analytical moves that directly answer the prompt and align with the rubric.

Examples of sure points include:

- An explicit thesis that restates the question and takes a clear position;

- One or two specific, relevant pieces of evidence (dates, names, quotes, events) that directly support your claim;

- A concise explanation of how that evidence connects to the thesis (the analysis move);

- A counterpoint or limitation when the prompt asks for nuance; and

- A concluding sentence that ties the paragraph back to the thesis, especially for long essays.

Why call them sure points? Because they’re small, high-probability wins. Even if you run out of time, well-placed sure points can separate a 2 from a 4 or a 4 from a 5 on an FRQ.

Where to Lock Your Sure Points: A Structural Map

Knowing where to place sure points is as important as knowing what they are. The structure below is deliberately simple so you can reproduce it during the pressure of the exam.

- Opening 2 minutes: Thesis + Roadmap. Your first sure point is the thesis. Put it in the first paragraph, and—if the prompt allows—add a one-line roadmap of the main points you’ll use. This immediately signals a direct answer to graders.

- Every body paragraph: Evidence + Analysis + Link. Lock in at least one specific piece of evidence (more if time allows), then one clear analytical sentence that connects evidence to the thesis, and finish with a link sentence that restates relevance.

- First and last sentences of each paragraph: prime real estate. Use them for sure points. The first sentence previews the point; the last sentence ties it back to the thesis.

- Conclusion: One-sentence clincher. Summarize quickly and reassert how your evidence supports the thesis. If time allows, add a quick implication or significance statement.

Quick Template (Use-It-Now)

Thesis (1–2 sentences): Restate the prompt + take a clear position. Roadmap (optional 1 sentence): 2–3 phrases naming your main points.

Paragraph (repeat 2–4 times):

- Topic sentence — claim that answers part of the prompt.

- Evidence — specific fact, quote, date, or example.

- Analysis — one sentence linking evidence to claim.

- Link — one sentence tying back to thesis.

Conclusion (1–2 sentences): Restate thesis and add significance.

Types of Sure Points by FRQ Genre

Humanities FRQs come in flavors—comparisons, causation, continuity/change, evaluation, and literary analysis. Knowing which sure points work best in each genre helps you respond precisely and efficiently.

Historical FRQs (USH, Euro, World): Causation and Evidence

Sure points for history FRQs lean on time, causality, and specific evidence (laws, battles, dates, figures). When prompted for causes or effects, give a primary cause (sure point) and support it with a named event or law. If the prompt asks for continuity/change, anchor a sure point in a specific year or key turning point.

- Example evidence: “The Market Revolution (early 19th century) increased economic specialization, evidenced by the rise of textile mills such as Lowell in the 1820s.”

- Analysis must connect how the evidence supports causation or change—for instance, showing mechanism (how industrialization changed labor patterns).

Literary FRQs (AP English Literature): Thesis and Close Reading

Literary FRQs reward a precise thesis and close reading. A sure point might be a concise interpretive claim about tone, theme, or character. Follow that with a short quotation or specific detail and one interpretive sentence that ties diction, imagery, or syntax to your claim.

- Example evidence: a short quote (fewer than 25 words for safe use) or a description of a scene.

- Analysis: Focus on “how” the language creates meaning—not just what it does.

Human Geography and Related Humanities: Concept + Application

For AP Human Geography or similar prompts, a sure point often combines a key concept (e.g., demographic transition model, central place theory) with a concrete example (a region, country, or dataset) that demonstrates the concept.

Language That Locks Points: Phrases Graders Love

Certain concise phrasing reliably signals analysis to a grader. Practice these and adapt them to your voice.

- “This demonstrates that …”

- “Consequently, …”

- “A crucial example is …”

- “This suggests that the author/leader/actor intended …”

- “Therefore, the effect was …”

These phrases help spotlight the analysis step—the connection between evidence and claim—which is often where students lose points when they only list facts without explaining them.

Timing Strategy: Where to Spend Your Minutes

Every minute matters. Here’s a recommended timing plan for a 40–50 minute long-form FRQ (adjust to the exact exam time):

| Phase | Minutes | Goal |

|---|---|---|

| Read & Outline | 4–6 | Understand the prompt; write thesis and roadmap; plan 2–4 paragraphs |

| Write Body Paragraphs | 25–30 | 1–2 evidence + analysis moves per paragraph; lock in sure points early |

| Write Conclusion | 3–4 | Restate thesis; add significance |

| Proofread & Add Quick Wins | 3–5 | Fix grammar, add a missing evidence or a clarifying sentence |

Note: The first 4–6 minutes are vital. That’s when you decide what your sure points will be and where to place them. Even a thin roadmap gives your essay coherence and helps graders recognize your plan.

Practical Examples — Turn Theory into Practice

Below are two condensed sample prompts and model paragraph fragments showing where sure points live. These are short for clarity; in your own answer, you would expand each analysis sentence into a full paragraph.

History Prompt (Sample)

Prompt: “Explain one economic cause and one political effect of the Industrial Revolution in the United States between 1800 and 1850.”

Sure-point paragraph fragments:

- Thesis: The Industrial Revolution between 1800 and 1850 spurred economic specialization—most visibly through factory growth—and politically strengthened national markets, which in turn prompted federal infrastructure investments.

- Evidence (economic cause): The development of textile mills, such as those in Lowell in the 1820s, shifted labor from household production to wage labor. Analysis: This specialization increased demand for coordinated transportation and credit systems, encouraging commercial ties across regions. Link: Thus, industrial growth set the stage for political efforts to support a national economy.

- Evidence (political effect): Federalized support for internal improvements (canals and roads) in the 1820s–1830s shows how economic change led to political advocacy for infrastructure. Analysis: As merchants and manufacturers sought stable markets, state and national leaders faced pressure to finance transport improvements to sustain economic growth.

Literature Prompt (Sample)

Prompt: “Analyze how the narrator’s tone shapes the reader’s understanding of the main conflict.”

- Thesis: The narrator’s ironic tone undercuts surface events to reveal the deeper moral conflict between duty and desire.

- Evidence: The narrator’s repeated understatement—phrases like “it was no matter” in a key scene—minimizes outward drama. Analysis: The understatement invites readers to infer tension beneath the surface, making the conflict internal and morally fraught rather than merely situational.

Common Mistakes That Lose Sure Points

Avoid these errors so your sure points actually earn credit:

- Listing facts without linking them to your thesis (evidence-only paragraphs).

- Vague or broad thesis statements that don’t answer the prompt directly.

- Using evidence that’s off-topic or only tangentially related.

- Running long on background and short on analysis—analysis is where points live.

- Failing to label or date historical evidence when the prompt asks for chronology.

Rubric Checklist — What a Grader Looks For

Use this brief checklist at the end of your essay or during proofreading to ensure your sure points are visible and effective.

| Item | Check (✔) | Why It Matters |

|---|---|---|

| Explicit thesis that answers the prompt | Directly addresses the question and frames the essay. | |

| Specific evidence named (person, date, quote, event) | Shows you know concrete details; graders reward specifics. | |

| Analysis linking evidence to claim | Turns facts into argument—this is where most points are earned. | |

| Concise conclusion that restates thesis | Seals the argument and reminds the grader of your claims. |

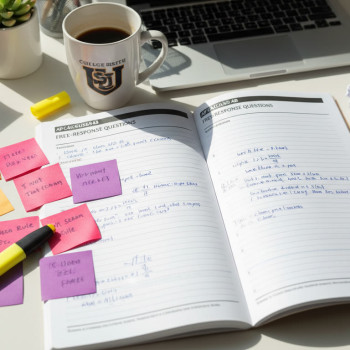

Practice Drills to Build Muscle Memory

Drilling sure points makes them automatic. Try these focused practice routines:

- Timed Thesis Drills (5 minutes): Read an FRQ prompt and write a one-sentence thesis + one-line roadmap. Aim for clarity and directness.

- Evidence Hunt (10 minutes): From a set of texts or notes, list three specific pieces of evidence you could use for a given thesis. Label each with a one-line analysis sentence.

- Paragraph Compression (15 minutes): Take a long practice paragraph and compress it to the essential sure points: topic sentence, one evidence line, one analysis line, link sentence.

- Peer Review Swap: Exchange essays with a partner and highlight where sure points occur and where they are missing. This helps train your grader’s eye.

How Tutoring Can Turn Sure Points into Scores

Personalized feedback accelerates improvement. One-on-one tutors (including options like Sparkl’s personalized tutoring) can help you identify recurring weaknesses—weak analysis, scant evidence, or fuzzy thesis statements—and give you targeted drills. Tutors can also simulate timed conditions and provide immediate, actionable edits so your sure points become second nature rather than occasional luck.

Final Checklist Before You Turn the Page

- Is your thesis explicit and responsive to the prompt?

- Does each paragraph have at least one sure point (evidence + analysis)?

- Are your examples specific and dated/named where relevant?

- Have you used clear analytical language—phrases like “this suggests” or “therefore”?

- Did you save 3–5 minutes to proofread and add any quick missing evidence?

Parting Thoughts — Confidence Through Simplicity

Exams can feel like high-wire acts, but you don’t have to perform acrobatics to score well on Humanities FRQs. By identifying and locking in sure points—crisp thesis statements, named evidence, and tight analysis—you convert uncertainty into earned points. Keep your structure simple, practice targeted drills, and use tutoring help when you want rapid, personalized progress.

Remember: graders are people looking for clear answers to clear questions. Give them those answers early and often, and you’ll find your scores reflect the care you put into strategic preparation. If you want guided, individualized training to turn these strategies into reliable performance, consider Sparkl’s personalized tutoring to pair structured practice with expert feedback and AI-driven insights.

Quick Start — 30-Second Checklist to Memorize Tonight

- Thesis in first 2 minutes.

- One named piece of evidence per paragraph.

- One sentence of analysis linking evidence to thesis.

- Conclude with a one-line clincher and proofread for 3 minutes.

Go practice—start small, build habits, and lock in your sure points until they become as natural as breathing. You’ve got this.

No Comments

Leave a comment Cancel