Why Sourcing Verbs Matter — And Why Examiners Notice

Every year thousands of students sit for AP history exams and craft answers from the same stack of documents. What separates a response that demonstrates thinking from one that simply summarizes is not just what you say about the documents, but how you say it. Sourcing verbs — the verbs you use to introduce, attribute, and analyze documents — are tiny tools that carry big meaning. Chosen well, they show the reader (and the grader) your judgment about author intent, reliability, perspective, and context. Chosen poorly or used mechanically, they flatten nuance and cost you points.

Quick example: two ways to introduce the same quote

Compare these openings to the same sentence from a nineteenth-century factory owner:

- “The author states that laborers are ‘content with their lot.'”

- “The factory owner claims that laborers are ‘content with their lot,’ a statement likely shaped by his need to present stability to investors and justify low wages.”

Both are grammatical. The second one, though, uses a sourcing verb with analysis — claims — and follows it with evaluation. That combination signals critical reading instead of mere reporting.

What Examiners Look For

Scoring rubrics for AP history essays reward evidence of historical thinking: sourcing, contextualization, corroboration, and interpretation. Using thoughtful sourcing verbs is part of demonstrating sourcing and interpretation. Examiners look for:

- Accurate identification of the author and their possible perspective.

- Appropriate verb choice — verbs that reflect degrees of certainty and intention.

- Follow-up analysis that explains why the source says what it does and how reliable it might be.

- Variation — not repeating the same neutral verb like “says” every time.

Remember: verbs create tone

Saying someone asserts something sounds stronger than saying they suggest it. Saying someone admits something implies contradiction or regret. Choose verbs to match the evidence and the inference you want the reader to draw.

Categories of Sourcing Verbs and How to Use Them

Below are practical categories of verbs with short instructions on when to use them. Think of this as a toolkit — you don’t need to use every category in one essay, but you should be able to choose the right tool for the job.

1) Neutral Reporting Verbs

Use these when you’re simply stating what the author wrote without adding judgment.

- Examples: states, notes, records, reports.

- When to use: Early in your paragraph as a transition into a quote or paraphrase. Follow up with analysis — don’t leave it bare.

2) Tentative / Suggestive Verbs

Use these to indicate inference or caution: the document implies something rather than declaring it outright.

- Examples: suggests, implies, hints, indicates.

- When to use: When the language in the source is ambiguous or when you want to signal interpretation rather than fact.

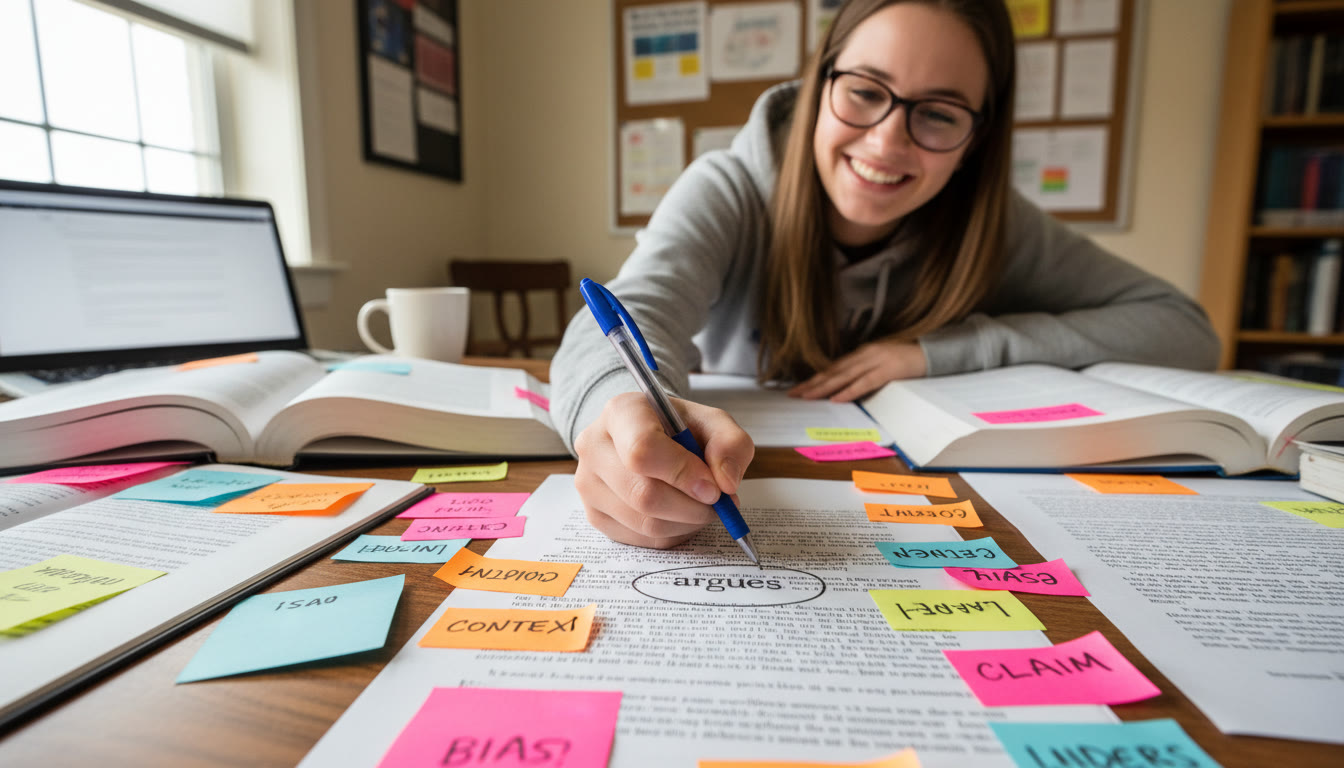

3) Judgemental / Interpretive Verbs

These verbs let you show that the author is acting with interest, persuasion, or bias.

- Examples: argues, contends, insists, advocates.

- When to use: When evidence shows the source is making a case, persuading, or presenting a clear viewpoint.

4) Skeptical / Problematic Verbs

Use these to highlight incompleteness, contradictions, or self-interest.

- Examples: claims, asserts, maintains, alleges.

- When to use: When the source appears defensive, self-interested, or contradicted by other evidence.

5) Revealing / Confessional Verbs

Use these when a document unintentionally exposes bias or provides revealing language.

- Examples: reveals, admits, concedes.

- When to use: When the author’s own wording undermines their credibility or exposes motives.

Concrete Examples That Score

Seeing verbs in context is the best way to learn them. Below are mock document attributions and short analyses that model how to use verbs to demonstrate sourcing.

Example 1 — A Political Speech

“In his 1898 address the senator asserts that expansion will bring civilization to ‘lesser peoples.'”

Follow-up: “The senator asserts this in a speech to a business audience seeking approval for overseas investments, which suggests his rhetoric is designed to justify economic aims under the guise of civilizational rhetoric.”

Example 2 — A Labor Memo

“A factory owner claims that wages are ‘adequate for contented families.'”

Follow-up: “This claim likely reflects the owner’s interest in presenting stable labor conditions to investors; worker testimony and strike records contradict this portrayal, reducing the memo’s reliability as a description of labor satisfaction.”

Example 3 — A Diary Entry

“A soldier’s journal entry reveals his exhaustion and fear after the battle.”

Follow-up: “As a private diary, the entry is candid and valuable for emotional perspective, though it is limited in scope and cannot speak for broader strategic assessments.”

How to Build an Analytical Sentence With a Sourcing Verb

A strong sourcing sentence usually contains three parts: identification (who wrote it), the sourcing verb, and a brief evaluation or context. Consider this formula:

- Author identification + sourcing verb + quoted/paraphrased content + reasoned evaluation (context, motive, reliability).

Example using the formula:

“A Northern factory owner argues that ‘efficiency will solve labor unrest,’ a claim that reflects his managerial perspective and market incentives, making his testimony useful for understanding employer attitudes but limited as evidence of workers’ actual experiences.”

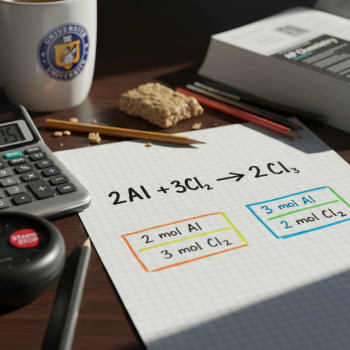

Table: Sourcing Verbs at a Glance

| Category | Sample Verbs | When to Use |

|---|---|---|

| Neutral | states, notes, reports | Simple attribution without judgment |

| Tentative | suggests, implies, indicates | When language is ambiguous or interpretive |

| Interpretive | argues, contends, advocates | To highlight persuasion or viewpoint |

| Skeptical | claims, alleges, maintains | When author interest or contradiction is likely |

| Revealing | admits, reveals, concedes | When language undermines credibility or discloses motive |

Putting It All Together in DBQs and LEQs

In Document-Based Questions (DBQs) and Long Essay Questions (LEQs), sourcing verbs should be integrated into paragraphs where you reference primary documents. They should never be dropped in as isolated attributions. Think in terms of flow: introduce the document, use an appropriate verb, then analyze what that verb choice exposes about perspective and reliability.

Paragraph structure checklist

- Topic sentence that ties the document to your thesis.

- Introduce the document with author and date.

- Use a sourcing verb that matches the evidence.

- Explain why the source wrote what it did (context, intended audience, purpose).

- Evaluate reliability and, if possible, corroborate with another document or outside evidence.

Common Pitfalls and How to Avoid Them

Students frequently fall into a few traps when using sourcing verbs. Spot the traps early and practice alternatives so your writing becomes more precise and persuasive.

Pitfall 1: Overusing “says”

Why it hurts: “Says” is neutral and safe, but repeated use flattens tone and suggests surface-level engagement. Fix: swap in interpretive or tentative verbs when your analysis supports them.

Pitfall 2: Choosing verbs that overstate certainty

Why it hurts: Using assertive verbs like “proves” or “demonstrates” without strong corroboration sounds doctrinaire. Fix: prefer “suggests” or “indicates” unless the document is explicit and corroborated.

Pitfall 3: Failing to follow the verb with analysis

Why it hurts: Attributions without evaluation read like summaries. Fix: always explain context, motive, or reliability immediately after the attribution.

Practice Prompts to Improve Your Verb Choices

Practice makes precision. Try these quick drills under timed conditions (5–8 minutes each) to build instinctive verb selection and analysis:

- Take a short editorial from a historical period and write three one-sentence attributions using neutral, interpretive, and skeptical verbs.

- Read a short speech excerpt and describe the speaker’s audience and purpose in one sentence using a verb from the Revealing/Confessional set.

- Compare two contradictory documents on the same event and write a short corroboration paragraph using at least two different sourcing verbs.

How Personalized Tutoring Can Help (A Natural Mention of Sparkl)

Language choice and subtle analytic moves are skills refined by feedback. That’s where personalized tutoring becomes valuable. A tutor can read several of your timed practice essays, point out repetitive verbs, suggest alternatives, and coach you on follow-up analysis that ties sourcing verbs back to thesis and evidence. Sparkl’s personalized tutoring—through one-on-one guidance, tailored study plans, and targeted practice—helps many students identify weak patterns in attribution and replace them with stronger, more nuanced phrasing. Tutors who track student progress can also provide AI-driven insights into recurring issues, so practice becomes more efficient and intentional.

Sample Paragraph With Excellent Sourcing

Below is a model paragraph showing how to attribute, analyze, and corroborate with sourcing verbs woven naturally into the flow:

“In a factory report dated 1910, the mill owner asserts that recent wage increases have resolved unrest among workers. This assertion likely serves a managerial purpose: presenting industrial harmony to potential investors and local officials. Contemporary newspaper accounts, however, indicate ongoing strikes and petitions for better conditions, which undermines the owner’s portrayal. Taken together, the owner’s memo is useful for understanding employers’ public narratives, while the press coverage corroborates that the memo reflects interest-driven rhetoric rather than a comprehensive account of worker sentiment.”

When to Use Outside Evidence Alongside Sourcing Verbs

Good essays balance documents and outside evidence. After sourcing the document and analyzing its perspective, bolster your claim with a quick external fact or trend that corroborates or challenges the document. This practice demonstrates breadth of knowledge and strengthens your interpretation.

Example

“The owner’s claim therefore reads as rhetorical; the strike records from 1909 and the Congressional testimony on labor conditions corroborate the workers’ ongoing grievances, suggesting the memo selectively frames events to defend the mill’s policies.”

Revision Strategies: Make Your Verbs Stronger

When you’re revising a timed practice essay, run a quick hunt-and-replace checklist to upgrade sourcing language:

- Find every “says” and decide whether to replace it with a verb that signals certainty (+argues), tentativeness (+suggests), or skepticism (+claims).

- After each attribution, add one brief clause explaining motive, audience, or reliability.

- Check for repetition — vary verbs across documents to display nuanced judgment.

Why This Small Change Boosts Scores

Examiners award points for historical thinking, not just content recall. Using sourcing verbs well demonstrates interpretation, perspective-taking, and the ability to weigh evidence. These are exactly the skills AP rubrics are designed to reward. Sourcing verbs function like punctuation for argumentation: they give the grader signals about your stance, your certainty, and your engagement with the source material.

Final Tips Before Test Day

- Practice with real past prompts and time yourself — include sourcing analysis in every document paragraph.

- Keep a short personal list of 10–12 verbs you can rely on and practice switching among them so they become second nature.

- Use precise verbs that reflect the evidence — don’t force a verb because it sounds impressive.

- When in doubt, be cautious: it’s usually safer to write “suggests” than “proves.”

- Use tutoring or targeted feedback if you are consistently weak at integrating sourcing and analysis — tailored guidance (like Sparkl’s 1-on-1 sessions and study plans) can accelerate improvements by pinpointing recurring issues and offering practice calibrated to your weaknesses.

Parting Thoughts

Sourcing verbs are deceptively small parts of your writing that carry outsized weight. They shape how your argument reads and how examiners interpret your work. With deliberate practice — choosing verbs that match evidence, following them with concise evaluation, and varying language across documents — you can transform ordinary summaries into persuasive historical analysis. Remember: clear attribution plus thoughtful evaluation equals credibility. Add in targeted practice, feedback, and the occasional sparkl of personalized tutoring, and you’ll find your essays clearer, stronger, and more convincing.

Go into your next timed write with a short verb list in your mind, and let precision guide your pen. The documents are not just things to quote — they are conversations you join. Choose your words as if you were responding directly to the author, and you’ll start to write like a historian.

No Comments

Leave a comment Cancel