Why Historical Passages on the SAT Feel Harder Than the Rest

If you have ever sat down to the SAT Reading section and felt your heartbeat inch up when you saw a history passage, you are not alone. Historical passages carry a special kind of challenge: unfamiliar language, dense sentence construction, implied assumptions about events, and writers who expect readers to know how to read between the lines. Those features can make these excerpts feel like a three-act play where the stage directions were written in another language.

This post peels back the curtain on why history passages are tougher, gives you concrete strategies to tackle them, and includes practice tips you can use immediately. We’ll balance practical reading habits with test-smart techniques, and show where targeted help — like Sparkl’s personalized tutoring, with 1-on-1 guidance, tailored study plans, expert tutors, and AI-driven insights — can speed your progress when you need it most.

What makes a historical passage different?

At a glance, historical passages might look like any nonfiction excerpt. But compared to contemporary nonfiction or social science writing, historical passages often have:

- Older or more formal diction — words, phrases, and idioms that aren’t part of everyday modern speech.

- Complex sentence structures — long dependent clauses, nested ideas, and parenthetical asides that demand slow parsing.

- Contextual assumptions — writers assume certain background knowledge about events, people, or institutions.

- Subtle arguments about causation or interpretation — authors rarely say “X caused Y” outright; they build nuanced positions.

- Primary-source style — letters, speeches, and eyewitness accounts emphasize voice and perspective over tidy argumentation.

Real-world comparison: reading a professor’s essay vs. a news article

Think of it this way. A modern news article announces the main point early, repeats it in different ways, and uses short sentences. A historical passage often reads like an older professor’s essay: the thesis is woven through the prose, claims are hedged, and the author assumes readers will supply context. Your eye has to do more work to extract the claim and the evidence.

Common pain points and how to fix them

1. Archaic or formal vocabulary

Why this trips students: unfamiliar words slow comprehension and force repeated rereads. Students waste time guessing vocabulary instead of focusing on the main idea.

Quick fix: focus on context clues before dictionary answers. Replace the unknown word with a simple synonym in your head and see if the sentence still makes sense. If the exact meaning matters for the question, mark it and move on; come back only if the answer depends on that nuance.

2. Long, tangled sentences

Why this trips students: long sentences with multiple clauses hide the main subject and verb, making it hard to track who is doing what.

Quick fix: mentally simplify. Break the sentence into bite-sized pieces: identify the main subject and verb first, then add modifiers. Writing a one-line paraphrase in the margin is one of the best time investments you can make.

3. Implicit arguments and subtle tone

Why this trips students: history writers often imply judgments instead of making explicit claims. SAT questions love to ask about tone, purpose, or the author’s stance — tasks that require nuance.

Quick fix: ask yourself two questions while reading — what is the author doing here? and why does the author care about this point? Find the sentence that shows the author’s judgment and underline it mentally.

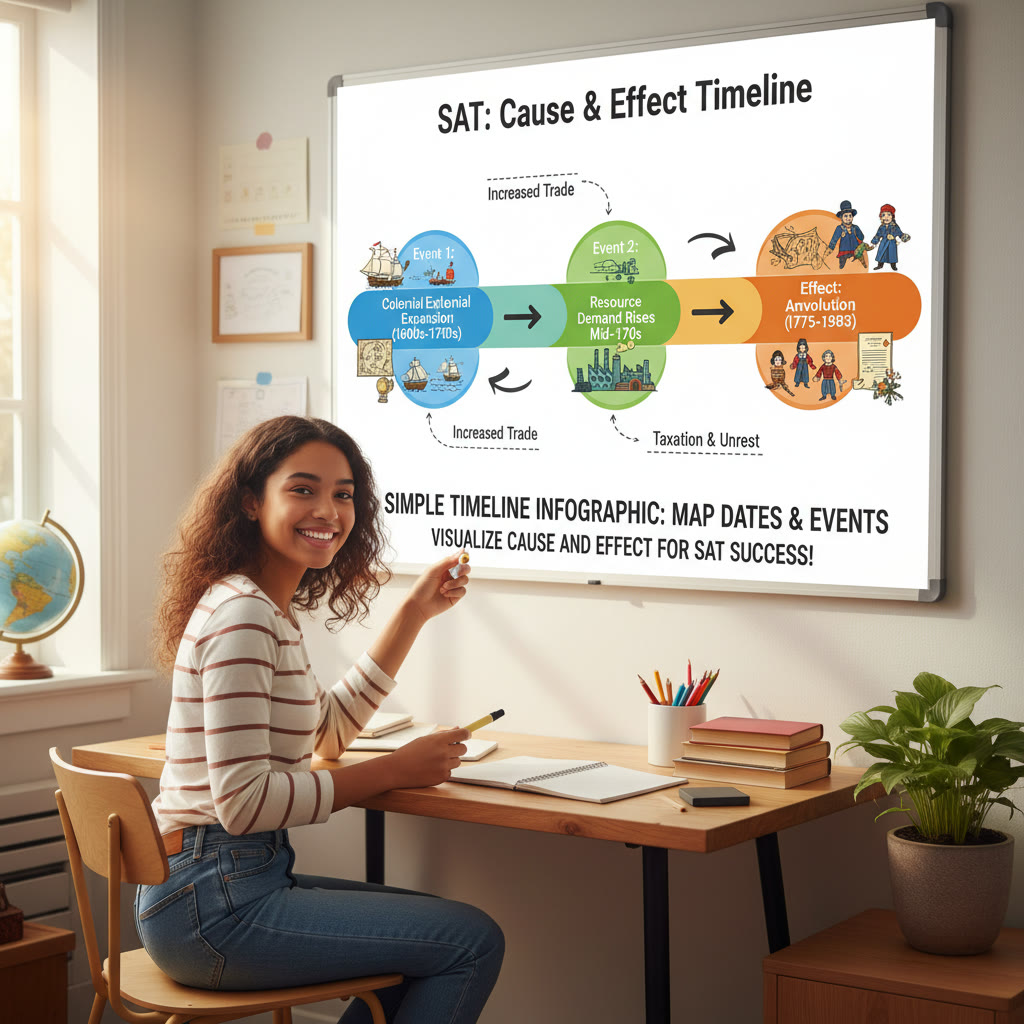

4. Density of evidence and cross-referencing

Why this trips students: historical passages often stack evidence — dates, quotes, descriptions — that can overwhelm you when you need to find support for a specific claim.

Quick fix: when a question asks for evidence, go back to the passage and find the smallest snippet that directly supports the answer. For paired evidence questions, match claims to lines rather than to large paragraphs.

5. Time pressure and decision fatigue

Why this trips students: once you’ve had one difficult historical passage, you may spend extra time on the next, creating a domino effect that eats your time budget.

Quick fix: manage time strictly. If a passage is taking too long, pick passage-question pairs that yield the most points quickly and flag the hard ones for later. Practice timed passages so your brain learns to skim effectively without losing comprehension.

Strategies that actually work on historical passages

Preview, but not too much

Many tutors say to preview the questions first; for historical passages, that can be a smart move. Skim the question stems to see what type of reading the test is asking for — main idea, tone, detail, inference, evidence. Then read the passage with those asks in mind. Don’t spend five minutes interrogating every question; a quick scan of question types helps focus your reading.

Annotate actively

Tiny annotations pay big dividends: underline the thesis sentence, circle dates, bracket transitions that mark changes in the author’s stance, and write one-line paraphrases of dense paragraphs. Those marks act as a map when a question sends you back.

Simplify and paraphrase

For every paragraph, try to create a one-sentence paraphrase. If the paragraph is dense, condense complex clauses into plain-English statements. That practice trains you to extract the point quickly under pressure.

Use process of elimination with historical thinking

With historical passages, wrong answers often fall into two categories: answers that are too specific to a detail or answers that rely on assumptions outside the passage. Eliminate anything that introduces facts not present in the text. Favor answers with careful wording: words like ‘most likely’, ‘suggests’, or ‘primarily’ often indicate correct choices when the passage is interpretive.

Time allocation: an evidence-based approach

Balancing reading and question time is an art. Below is a practical allocation for a single SAT Reading passage with corresponding questions. Use it as a starting point and adjust as you become faster.

| Task | Suggested time | Why |

|---|---|---|

| Quick question preview | 30 seconds | Identifies question focus so you read with purpose |

| Read and annotate passage | 2 minutes | Paraphrase main idea, mark evidence, note tone |

| Answer direct detail questions | 1 minute | Often quick if annotation is good |

| Answer inference/tone/evidence questions | 2 minutes | Requires returning to lines and thinking about nuance |

| Check flagged or hard items | 1 minute | Resolve remaining uncertainties without losing time |

Practice drills that build muscle memory

1. The 60-second paraphrase drill

Pick a paragraph in a historical essay and give yourself 60 seconds to write one sentence that captures the main idea and the author’s stance. This trains you to find the heart of the paragraph fast.

2. The evidence-match game

Write five claims about a passage and then find the shortest quote or line that supports each claim. This drill improves your ability to answer SAT evidence questions, which often hinge on identifying the exact line that supports a choice.

3. Vocabulary-by-context challenge

Take ten unusual words from old texts and create simple definitions based on surrounding sentences only. Compare to dictionary meanings later. Over time you’ll guess better and waste less time.

Worked example: a small practice question and explanation

Imagine a short excerpt where an author describes a political reform as ‘a cautious recalibration rather than a decisive rupture.’ A question asks: ‘The author’s tone in calling the reform a recalibration is best described as:’

- A. enthusiastic

- B. skeptical

- C. nostalgic

- D. indifferent

How to approach it: circle the phrase ‘cautious recalibration’ and note the contrast with ‘decisive rupture.’ The author is deliberately choosing language that downplays radical change. That signals skepticism about strong claims. Correct answer: B, skeptical. The clue is the qualifier ‘cautious’ which softens praise.

Common mistakes students make

Mistake 1: Relying on outside knowledge

The SAT tests what the passage says, not what you know. If a passage references a historical figure or event, don’t assume facts you learned elsewhere unless the passage confirms them. Wrong answers often sneak in by appealing to outside knowledge.

Mistake 2: Ignoring transitional language

Words like ‘however,’ ‘nevertheless,’ and ‘yet’ are signposts. Missing them means missing shifts in argument. Annotate transitions to catch changes in tone or emphasis.

Mistake 3: Over-literal reading

Sometimes students read a sentence so literally that they miss the author’s implied meaning. Practice inferring the point the author intends, not only the literal facts stated.

How to structure study time each week

Consistency beats marathon sessions. Here’s a sample weekly plan that balances comprehension, speed, and strategy practice.

- Day 1: One timed historical passage, annotations, and review (focus on paraphrase practice).

- Day 2: Vocabulary-by-context session (30–45 minutes) and quick review of mistakes.

- Day 3: One paired passage or longer historical excerpt to practice evidence questions.

- Day 4: Review errors and retake one passage you missed; drill on transitions and tone.

- Day 5: Mixed practice (one science or social science passage to keep skills flexible).

- Weekend: Full practice section under timed conditions plus reflection on patterns.

When to get targeted help

Some students plateau because they keep making the same mistakes: misreading tone, missing evidence, or spending too long on vocab. At that point, personalized feedback accelerates improvement. Working 1-on-1 with an experienced tutor brings two big advantages: tailored study plans focused on your weak spots, and live modeling of how to annotate and paraphrase under pressure. Sparkl’s personalized tutoring blends expert tutors with AI-driven insights to identify patterns in your errors and create a study plan that evolves as you improve. That kind of focused support is especially valuable when historical passages slow your progress.

Small habits that add up

Improving at historical passages isn’t only about drills. Small daily habits accumulate: read one short primary-source excerpt a day, keep a vocabulary log of unusual words you find, and practice rephrasing dense sentences into everyday language. Over time, the unfamiliar becomes familiar.

Reading suggestions for slow, deliberate exposure

- Short memoir excerpts or letters — these help you tune into voice and perspective.

- Edited historical essays — they show how historians frame arguments and use evidence.

- Classic speeches or public documents with annotations — useful for practicing tone detection.

Final checklist before test day

- Practice at least three full reading sections under timed conditions.

- Review and annotate your two most recent mistakes until you can explain them aloud.

- Develop a simple marking system (underline thesis, bracket evidence, circle transitions).

- Plan your timing approach and stick to it during practice.

- If you still hit a wall, consider a short series of focused tutoring sessions to break bad habits and refine your technique.

Parting thought: historical passages as a strength

Here’s the cheerful truth: historical passages are predictable in what trips students up. Once you recognize the patterns — archaic diction, dense sentences, implicit arguments — you can train specific muscles to handle them. With deliberate practice, good annotation habits, and the occasional targeted nudge from a tutor, those once-dreaded passages become opportunities to score reliably.

If you want a structured approach that adapts to your mistakes, tools like Sparkl’s personalized tutoring can fit naturally into a study plan, giving 1-on-1 guidance, tailored study plans, expert tutors, and AI-driven insights that help you improve faster. Use practice, reflection, and targeted help where it makes sense, and historical passages will stop being a stumbling block and start being a predictable part of your success.

No Comments

Leave a comment Cancel