Why SAT Science Passages Deserve Your Attention

When students hear “science passages” on the SAT, many imagine dense textbook excerpts and intimidating graphs. The truth is kinder: SAT science passages are predictable puzzles. They reward a few sharp habits more than encyclopedic knowledge. If you learn the patterns the College Board favors and practice applying consistent strategies, you can move from guessing to confident, fast answers.

This article walks through the common patterns that show up in SAT science passages, explains the thinking behind each pattern, and gives practical drills and a study plan you can follow. Along the way you will see examples, comparisons, and realistic approaches you can use during practice and on test day. If you ever want personalized help, Sparkl’s personalized tutoring can provide 1-on-1 guidance, tailored study plans, expert tutors, and AI-driven insights to focus your practice on the patterns that matter most.

What Makes SAT Science Passages Unique

They test thinking, not encyclopedic knowledge

The SAT rarely expects you to know advanced science facts. Instead it asks you to read data, interpret experimental setups, and evaluate arguments. You are asked to do three things consistently: extract information, apply simple reasoning, and choose the best-supported answer from the passage. When you treat each passage as a compact argument with evidence, the science section becomes manageable.

Common passage topics and their disguises

Passages may look like biology, chemistry, physics, or Earth science, but the subject is often secondary to the task type. A biology passage might primarily test graph reading, while a physics passage might test experimental design. Recognizing the task underneath the topic is one of the key patterns we will emphasize.

Key Patterns to Recognize

Pattern 1: Passage structure and paragraph function

Science passages follow a logical structure. Recognizing the role of each paragraph speeds up comprehension:

- Introductory paragraph: frames the question or claim and usually contains the hypothesis or the research question.

- Methods/experimental paragraphs: describe how data were collected, including variables and controls.

- Results paragraphs: often contain figures or tables and summarize outcomes.

- Discussion/conclusion: interprets the results and may mention alternative explanations or limitations.

When you skim, mentally label paragraphs by function. That way, when a question asks about methodology, you know which paragraph to jump to.

Pattern 2: Data-first vs text-first passages

Some passages are data-first: they give a table or graph and ask you to interpret it. Others are text-first: they describe an experiment and then present results. The strategy varies slightly:

- Data-first: start with the figure. Read the axes, units, and legends. Often questions require extracting numbers, computing a ratio, or recognizing a trend.

- Text-first: skim the methods and conclusions, then reference figures as needed. The passage narrative tells you which variables matter.

On the real test you’ll see both types. A useful habit is to glance at any figure right away to see where the data live, then read the paragraph that explains how those data were collected.

Pattern 3: Graphs and tables have their own language

Graphs and tables are precise. Common traps arise from misreading axes, confusing absolute vs relative change, or missing units. Practice a small set of micro-skills:

- Read axis labels first. Are you looking at time, concentration, distance, or percentage?

- Pay attention to scale. Non-zero origins or logarithmic scales change interpretation.

- Distinguish slope from height. Two curves can cross even if one is higher at a point.

- Compute percent change versus absolute change. For example, going from 2 to 4 is a 100% increase, while 20 to 22 is a 10% increase despite both being +2.

Here is a small example. Suppose a graph shows population A growing from 10 to 20 and population B growing from 100 to 110 over the same interval. If a question asks which population doubled, the correct answer is A. If it asks which increased by a larger percentage, again A. If it asks which increased by a larger absolute number, both increased by 10, so they tie. Reading carefully avoids traps.

Pattern 4: Author stance and argument shifts

Many questions hinge on subtle shifts in the passage’s argument. Authors may propose a hypothesis, present results that partly support it, and then offer caveats. Typical traps:

- Choosing an answer that matches the hypothesis rather than the evidence.

- Confusing the author’s speculation with the passage’s conclusions.

- Missing hedging words such as “suggests”, “may”, or “consistent with” which reduce the strength of a claim.

Ask: does the passage assert a conclusion or merely propose an interpretation? Questions that ask “which is supported by the passage” want evidence-based answers, not speculation.

Pattern 5: Experimental setups and controls

Questions about experiments test your understanding of variables and controls more often than complex methodology. Look for:

- The independent variable: what the experimenter changed.

- The dependent variable: what was measured.

- Controls: which factors were held constant or compared to a baseline.

- Potential confounders or alternative explanations noted in the discussion.

If a question asks what change would invalidate the conclusion, consider whether the new factor could explain the results without the proposed mechanism.

How to Use Pattern Recognition in Real Time

Skimming vs deep reading: when to use each

Time is a premium. Use a two-pass approach:

- First pass (20-40 seconds): glance at the passage title, sentence topic, and any figures or tables. Identify the passage type and note the independent/dependent variables if an experiment is described.

- Second pass: read questions in groups. For data questions, return to the figure. For method or inference questions, return to the relevant paragraph. Read only the necessary lines—don’t re-read everything.

This approach reduces wasted time and improves accuracy because you approach questions with the context already in mind.

Annotating effectively

Annotation should be quick and functional. A few useful marks:

- Circle variables and units when an experiment is described.

- Underline the sentence that states the main result or the author’s conclusion.

- Put a square or star next to any paragraph that explicitly mentions control conditions or potential confounders.

These tiny marks are especially valuable when you jump back and forth between passage and questions.

Question strategies: common question types and approaches

Here are typical question types and how pattern recognition speeds up answers:

- Direct data retrieval: read the figure or table carefully. If units differ, convert before comparing.

- Inference: find the sentence in the passage that supports the inference. Avoid answers that require outside knowledge.

- Methodology: identify independent/dependent variables and controls. The answer usually references the setup described in the passage.

- Dual-referent questions: sometimes a question references two parts of the passage. Find both parts and see how they connect.

Common Pitfalls and How to Avoid Them

Trap answers that look right but aren’t supported

Answer choices often include plausible statements that the passage does not support. To avoid these traps, create a simple rule: if the passage does not say it, you cannot pick it. Many students fall for “sounds right” instead of “supported by text.”

Mistaking correlation for causation

Science passages often present correlational data. The correct answer will rarely claim causation unless an experiment with proper controls is described. When you see correlation, think “associated with” rather than “caused by,” unless the passage explicitly demonstrates a causal mechanism.

Math mistakes

Simple computations appear frequently. Avoid common errors by estimating first, then computing if needed. If a choice is far from your estimate, it’s probably wrong. Practice ratio and percent problems on a timer to make computation automatic.

Practical Examples and Micro-Drills

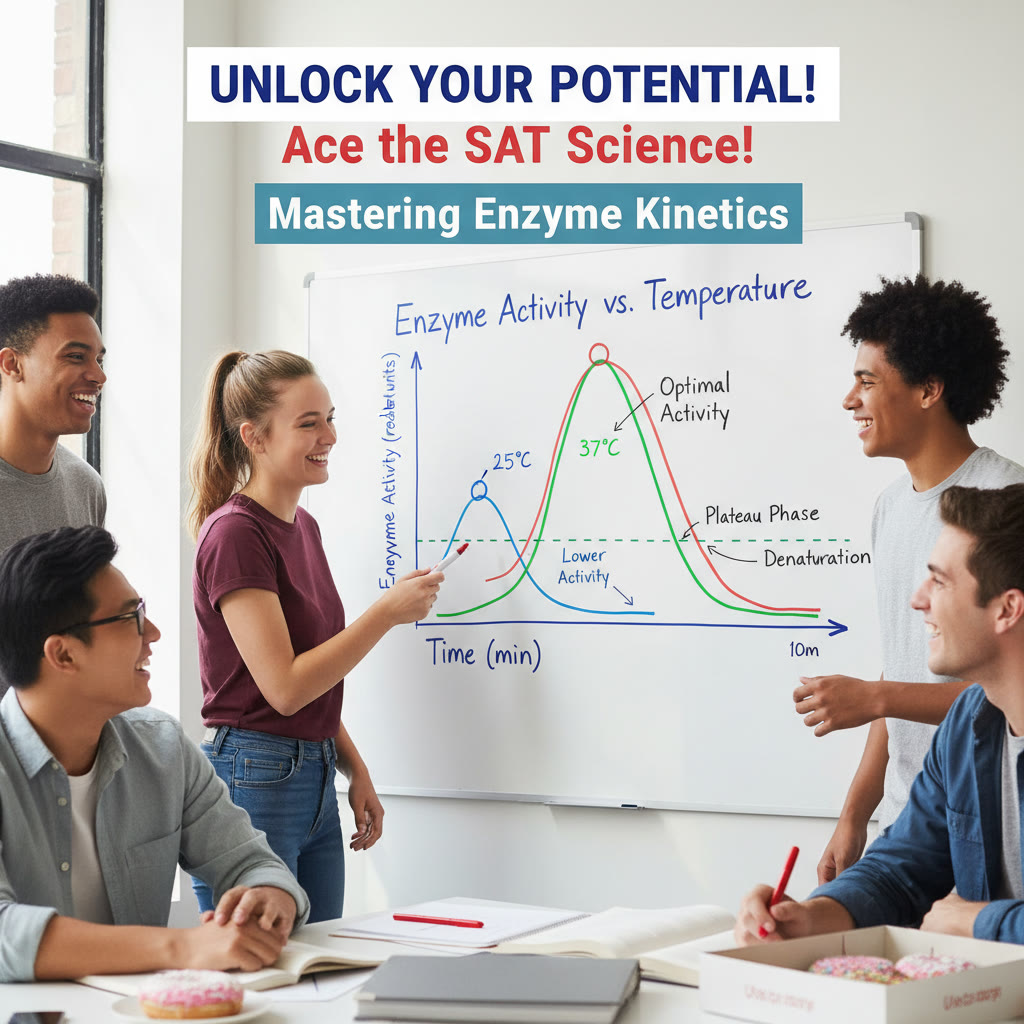

Example 1: Reading a multi-line graph

Imagine a graph showing enzyme activity over time at three different temperatures. Temperatures A and B show similar curves but shifted; temperature C plateaus early. A question asks which temperature most likely denatures the enzyme. Look for the curve that drops or plateaus unexpectedly—that is the denaturing indicator. The text may note experimental conditions confirming your choice.

Example 2: Experimental control question

Suppose an experiment tests plant growth under light of different wavelengths but plants also received different fertilizer. A question asks which change would make results more reliable. The correct answer: make fertilizer constant across groups. This highlights isolating the independent variable as a core idea.

Micro-drills to practice regularly

- Pick 10 practice graphs and label axes, independent/dependent variables, and the main trend in 60 seconds each.

- Given a short experimental paragraph, list controls and potential confounders in 90 seconds.

- Read a passage and underline the core claim and the sentence that supports it, then summarize the evidence in one line.

Study Plan: Build Pattern Recognition Over Time

Below is a focused 4-week plan you can adapt to your schedule. The goal is to develop habits rather than cram content. If you have more time, repeat the cycle and increase complexity. If you prefer personalized guidance, Sparkl’s personalized tutoring can tailor this plan to your strengths, providing targeted practice, expert tutors, and AI-driven insights to highlight which patterns you still need to master.

| Week | Focus | Daily Routine (about 45-60 min) |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Foundations: graphs, units, and passage structure |

|

| 2 | Experimental design and controls |

|

| 3 | Timing and mixed practice |

|

| 4 | Full practice tests and targeted weak-skill work |

|

How to review effectively

Review is where learning sticks. For each wrong answer, write a one-line reason for the error. Was it a misread axis, a math slip, or an inference beyond the passage? Tally your errors weekly. If controls or graph reading account for many mistakes, focus the next week on those micro-skills. A tutor or coach can accelerate this loop by pointing out subtle patterns you might miss on your own.

Timing Tips for Test Day

Allocating time across passages

You have roughly one minute per question on the SAT. For many students a useful rhythm is:

- 30-60 seconds to preview passage and figures

- About 90 seconds per passage question on average, with faster ones taking less time

- If a question takes more than 3 minutes, mark it, move on, and return if time remains

Don’t get stuck on one tricky graph or question. Use the two-pass approach to answer easier questions first and build momentum.

Keeping calm when a passage is unfamiliar

A passage that looks foreign is often testing familiar skills. Slow down, identify the independent/dependent variables, and find the sentence with the result. Remember: the passage gives everything you need. External knowledge is rarely required.

How Tutors and Technology Can Help

There is no substitute for deliberate practice, but effective tutoring can speed progress. A tutor who understands SAT patterns will help you identify recurring mistakes, strengthen weak micro-skills, and practice under timed conditions. If you choose to work with a service, look for features that matter: 1-on-1 guidance, tailored study plans, expert tutors who explain reasoning, and tools that produce actionable insights. Sparkl’s personalized tutoring blends these elements with AI-driven insights that highlight which patterns you still need to practice, making your study time more efficient.

Wrapping Up: Pattern Mastery Beats Panic

Science passages on the SAT are puzzles built from a small set of repeatable pieces: a hypothesis, a method, a result, and an interpretation. If you train yourself to recognize paragraph function, read graphs with intention, and test claims against passage evidence, you’ll transform intimidating passages into predictable work. Use focused micro-drills to build fluency, follow a short study plan, and review errors with care. With deliberate practice and strategic help—whether from a coach or Sparkl’s personalized tutoring—you can turn pattern recognition into consistent points on test day.

Quick checklist to take away

- Label passages by paragraph function as you read.

- Glance at figures immediately and read axis labels first.

- Distinguish correlation from causation and watch for hedging language.

- Annotate variables and controls in experimental descriptions.

- Practice timed micro-drills and review mistakes by type.

Nice work getting this far. Science passages reward calm, curiosity, and a few smart habits. Keep practicing the patterns above, and you’ll be surprised how quickly your confidence and score improve.

No Comments

Leave a comment Cancel