Why Command of Evidence Matters — and Why It’s Actually Fun

If you’ve been practicing for the Digital SAT, you’ve probably noticed a recurring theme: you’re not just asked what an author says — you’re asked to point to where the author supports that idea. Those are Command of Evidence questions, and they’re one of the clearest opportunities on the test to show precision, close reading, and logical thinking. Get them right, and you earn clear, relatively objective points. Miss them, and you often lose both the main-question point and the connected evidence point.

This guide takes you through exactly what Command of Evidence questions look like on the Digital SAT, why they’re designed the way they are, and step-by-step ways to practice so these questions become second nature. We’ll include examples, a study sequence you can use, a practice table to track progress, and a few real-world tips — including how targeted 1-on-1 help, like Sparkl’s personalized tutoring, can plug gaps fast.

What Are Command of Evidence Questions?

At their core, Command of Evidence questions are paired or linked questions. The first part often asks you to interpret a passage — identify the main idea, the author’s purpose, or the meaning of a line. The second (the Command of Evidence part) asks: which part of the passage best supports that answer? Instead of testing memory or vague impressions, the test asks you to show the textual proof for your conclusion.

Typical Formats You’ll See

- Primary question + follow-up: Example — “The author’s purpose is X.” Followed by: “Which sentence best supports the answer to the previous question?”

- Paired inference + evidence: You pick an interpretation and then select the sentence or phrase that most directly justifies it.

- Evidence that strengthens or weakens an argument: Sometimes you’ll be asked which detail most strongly supports or undermines a point.

The Exam Mindset: How to Think Like the SAT Writers

Instead of reading like you’re browsing an interesting article, read like an investigator. The test-writers want to see (1) that you can find the best-supported answer to a question about the passage and (2) that you can locate the textual anchor that justifies that answer.

Two rules to adopt immediately:

- Rule 1 — Answer the first question cleanly before you read evidence choices. If the main question is “What does X mean?”, lock in your answer in your head (or mark it). Then move to the evidence choices with that answer in mind.

- Rule 2 — The best evidence is specific and direct. Not an idea that just generally relates, but a sentence or phrase that, when read, makes your main-answer obvious.

Step-by-Step Strategy for Every Command of Evidence Pair

Here’s a consistent workflow that students can follow under timed conditions. Practice it until it feels automatic.

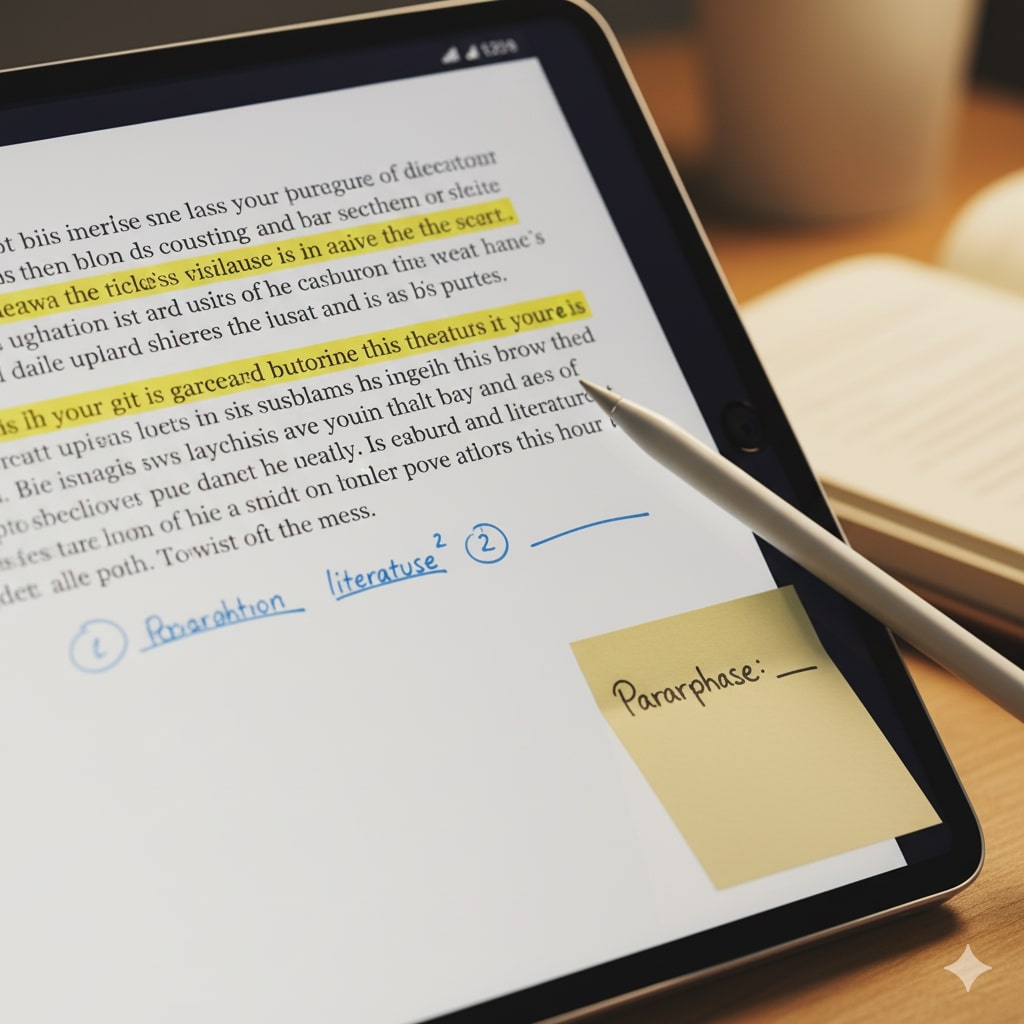

- Step 1 — Read the target sentence/line. If the primary question points to line numbers, read those lines and the sentence before/after. For a broader main question, skim the paragraph that contains the key idea.

- Step 2 — Paraphrase the main-question answer. In one short phrase, restate what you think the answer is. E.g., “Author argues technology improves empathy.” Keep it brief.

- Step 3 — Scan evidence choices for the support function. Ask: which choice would make my paraphrase obvious to someone who hadn’t read the rest of the passage?

- Step 4 — Eliminate weak links. Cross out answers that are too general, relate indirectly, or introduce new ideas that the passage does not support.

- Step 5 — Re-check context. Once you pick evidence, read the surrounding sentence(s) in the passage to confirm it actually supports your main answer and isn’t taken out of context.

Quick tip

When the evidence choice contains an extreme word (always, never, completely), be skeptical. Evidence is usually more subtle and specific — not absolute.

Examples — Walkthroughs You Can Practice

Real practice beats theory. Below are two stylized examples that show how to apply the steps above. Work through them slowly, then time yourself once you feel comfortable.

Example 1 — Literary Passage (short)

Main question: “What does the narrator mean when she says the house was ‘warmed by an invisible hearth’?”

Follow-up: “Which sentence best supports the answer to the previous question?”

How to approach it:

- Paraphrase: The narrator means that a feeling or memory created comfort, not an actual fire.

- Scan evidence choices for sentences that point to feeling/memory rather than physical heat.

- Pick the sentence that mentions a memory connecting family and comfort, read one line before and after to confirm.

Example 2 — Informational Passage (science/history)

Main question: “The author uses the example of the 1910 bridge collapse to illustrate which point?”

Follow-up: “Which phrase most directly supports the answer to the previous question?”

How to approach it:

- Paraphrase: The example illustrates how small design oversights can cause large failures.

- Find the evidence option that names the oversight or describes the causal chain, not the general aftermath.

- Confirm context; if the phrase is about consequences (deaths), it’s related but not the best support.

Common Traps and How to Avoid Them

- Trap — Choosing supportive tone instead of direct evidence. Avoid choices that merely echo the main idea in tone; pick the one that explicitly explains or demonstrates it.

- Trap — Confusing correlation with causation. If the evidence shows two events happened together but not that one caused the other, it may not support a causal claim.

- Trap — Overrelying on memory. Always re-check the passage. Memory can mislead, especially under pressure.

- Trap — Picking the most specific-sounding sentence even when it introduces content not in the main interpretation. Specificity helps, but accuracy is key.

Practice Routines — How to Build Muscle Memory

To turn this strategy into automatic behavior, practice deliberately. Block time, measure progress, and vary passage types.

Weekly Practice Plan (6 weeks)

- Week 1–2: 20 minutes/day focused on paired questions; no timer for accuracy training.

- Week 3–4: 30 minutes/day with timed sections (simulate 2–3 pairs per 12 minutes). Review every wrong answer and write why it’s wrong.

- Week 5: Full timed Reading & Writing section practice once per week; analyze Command of Evidence accuracy rates.

- Week 6: Blend with official practice tests and do mixed review; focus on stamina and quick re-checking habits.

Micro-practice ideas

- Daily 10-minute “spot checks” where you read a short paragraph and pick the best evidence sentence for a one-sentence conclusion.

- Create flashcards with paraphrases on one side and the supporting sentence reference (line number/phrase) on the other — practice matching them.

Tracking Progress — Use This Simple Table

Keeping data helps you see improvement and identify stubborn mistakes. Use the table below each week, then summarize trends.

| Week | Pairs Attempted | Command of Evidence Accuracy (%) | Most Common Mistake | Action Next Week |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 15 | 60% | Rushing to evidence choices | Slow down: paraphrase before reading choices |

| 2 | 20 | 68% | Choosing related not direct evidence | Practice identifying “direct link” sentences |

| 3 | 25 | 75% | Context errors | Read one sentence before/after evidence lines |

How to Use Official Practice Effectively

Official practice (College Board’s materials and digital practice on Khan Academy) is gold because it mirrors the structure and language of the Digital SAT. But not all practice is created equal: quality beats quantity.

- Work small sets with full review: do 5–10 pairs and then spend time diving into every mistake.

- Annotate the passage: underline verbs that signal claims (argues, suggests, implies) and circle evidence words (because, therefore, for example).

- Simulate the device: practice on a tablet or laptop so scrolling, highlighting, and navigation feel natural.

Real-World Reading Habits That Improve Evidence Skills

Outside test prep, cultivate reading habits that sharpen evidence detection:

- Ask “Why?” while reading news or editorials: identify one sentence that justifies the headline claim.

- Summarize short articles in one sentence, then point out which paragraph backs that summary.

- Discuss reasoning with friends: debating an article forces you to look for textual anchors.

How Sparkl’s Personalized Tutoring Can Help — When It Fits

Many students make leaps faster with focused, individualized feedback. If you ever feel stuck — for example, repeating the same mistake despite practice — a few tailored sessions can pinpoint the problem and fix it. Sparkl’s personalized tutoring offers targeted 1-on-1 guidance, tailored study plans, expert tutors, and AI-driven insights that highlight patterns in your mistakes. This isn’t about doing the work for you; it’s about making each practice minute more powerful by correcting misconceptions and reinforcing good habits.

Some students use three 1-on-1 sessions to change a habit (like paraphrasing before choosing evidence); others build longer plans. If you opt for tutoring, look for tutors who ask students to show their thinking — that’s the skill the SAT rewards.

Time Management: Quick Ways to Save Seconds (That Add Up)

On a digital test, seconds matter. Building a fast, reliable pattern is more valuable than racing randomly.

- Always paraphrase in two to five words — it takes 3–6 seconds and saves time downstream.

- If the main question is trivial (e.g., vocabulary in context), answer it and then immediately highlight the sentence you used to decide — don’t re-read the whole paragraph.

- Use the digital highlighter to mark the sentence you think is evidence before moving to the evidence choices.

Interpreting the Tough Ones — When Evidence Is Subtle

Sometimes the best evidence isn’t a single declarative sentence but a small detail that implies the answer. In those cases, do three things:

- Connect the inference chain: write down (mentally) the few steps that link detail to claim.

- Confirm the passage supports each link; if any step relies on outside knowledge, it’s probably not the best evidence.

- Prefer evidence that shortens the inference chain — the SAT rewards direct textual ties.

When to Guess — and How to Make Educated Guesses

If time’s short, use elimination aggressively. Many wrong evidence choices are either too broad, introduce new ideas, or rely on tone rather than content. Eliminate those first. If you’re down to two and both look plausible, pick the one that most directly names or explains rather than the one that simply echoes.

Putting It All Together — A Full Practice Session Blueprint

Here’s a single-session plan you can use once or twice a week. It mixes deliberate skill-building with measurement so you keep improving.

- 10 min: Warm-up — read two short passages and paraphrase their main claims out loud.

- 25 min: Focused practice — 12 Command of Evidence pairs, no timer first half, timed second half.

- 15 min: Deep review — for every incorrect answer, write a 1–2 sentence explanation: why your choice was wrong and what the best evidence does differently.

- 10 min: Reflection & planning — log results in your progress table and pick one micro-skill to practice next session (e.g., “reading context lines before confirming evidence”).

Final Thoughts — Confidence Is a Skill Too

Command of Evidence questions give you an advantage because they reward process. You can build a repeatable, test-ready process: read carefully, paraphrase, choose the sentence that directly proves your paraphrase, and confirm in context. Over time this becomes faster and more accurate — and more satisfying. There’s a quiet pleasure in finding the exact line that does the work; it’s like solving a small puzzle.

If you find a stubborn pattern in your mistakes, targeted help — for instance Sparkl’s 1-on-1 tutoring with tailored study plans and AI insight into your error patterns — can be the most efficient next step. Small, well-targeted adjustments often produce the biggest score gains.

Trust the process. Practice thoughtfully. And remember: mastering Command of Evidence isn’t about memorizing tricks; it’s about learning to read with the exacting clarity the SAT asks for. Do that, and you’ll see those improvements show up where it counts.

Quick Checklist Before Your Next Practice

- I paraphrase the main answer before looking at evidence choices.

- I look for evidence that directly demonstrates, not just suggests, the main point.

- I always re-read one sentence before and after my chosen evidence.

- I log mistakes and pick one micro-skill to fix each week.

- If stuck, I consider a short series of focused tutoring sessions to break the pattern.

A Final Encouragement

The Digital SAT’s Command of Evidence questions reward curiosity and careful reading — two skills you’re already building in school. Treat each practice set like a detective case. Find the line that solves it. Over weeks, that detective habit will translate to steady score gains. Good luck, and happy practicing.

No Comments

Leave a comment Cancel